Take yourself back to the 1960s and 1970s when Jewish hippies envisioned creating their own brand of Judaism. Kosher food mixed with marijuana. Come as you are davening with cushions in a circle, instead of chairs facing a bima. Potluck dinners, in both meanings of the word. Some traditional prayers in, others out. Fully egalitarian services long before more established movements recognized women as spiritual leaders. Men and a woman even going to an outdoor mikvah together (Okay, it was skinny-dipping mixed with traditional mikvah prayers.)

Take yourself back to the 1960s and 1970s when Jewish hippies envisioned creating their own brand of Judaism. Kosher food mixed with marijuana. Come as you are davening with cushions in a circle, instead of chairs facing a bima. Potluck dinners, in both meanings of the word. Some traditional prayers in, others out. Fully egalitarian services long before more established movements recognized women as spiritual leaders. Men and a woman even going to an outdoor mikvah together (Okay, it was skinny-dipping mixed with traditional mikvah prayers.)

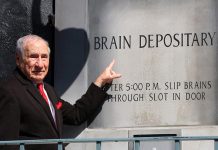

Author David Kronfeld says his account is a fictionalized version of the co-educational havurah with which he worshiped and lived in a rambling old house that easily accommodated 20 persons and occasionally was filled to bursting during special holidays such as Purim and Yom Kippur. His book is filled with stories about the relationships between members of the outside world (including parents), and relationships among the members, including sexual dalliances, theological disagreements, mutual support, and lots of teasing.

As Jewish hippies living together, they didn’t have to explain their hippiedom to other Jews, nor their Judaism to other hippies. They were a mostly self-contained breed of their own, making up and breaking rules as they saw fit, but nevertheless hewing to a more observant form of Judaism than what is found today in many mainstream temples and synagogues.

Kronfeld is a marvelous writer, capable of bringing you into the moment. He tells of the difficulty and embarrassment members of the Havurah experienced when a homeless woman, who clearly was mentally ill, kept demanding admittance and eating prodigious amounts of food that others had paid for. He explains how difficult it was for them to finally turn away a fellow Jew, after she repeatedly refused their offers to find her professional help.

He also writes about members of the Havurah attending services at a nearby synagogue in a Boston suburb where the membership had been so diminished that only a few elderly Jews remained, worrying if they could somehow keep their doors open. It was clear that these elderly Jews wanted the young members of the Havurah — who by and large were graduate students at various Boston-area universities — to merge with their congregation, but the silent appeal went unheeded. It was hard enough for the Havurah to keep itself together, much less to take on the responsibilities of a formal synagogue building.

Nearly every chapter in this book revealed a deep knowledge of Jewish religion and tradition, mixed with an impatience for traditional religious formats. The Havurah was a glorious experiment, but like the old synagogue, the Havurah had difficulty replenishing its membership. Eventually, it faded away, except in the memories of its alumni — no, my mistake, per the letter below from Debra Cash, it didn’t fade away; it transformed.

I highly recommend reading this book for anyone who yearns for new ways to express their spirituality. One big difference between then and now: Smoking pot, or weed as it is more popularly called, is legal, at least in some states including right here in Califfffornia.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World