People who explored an online YIVO Institute for Jewish Research exhibit about the diary of Beba Epstein, a 13-year-old girl who survived the Holocaust after hiding in Vilna, told YIVO that prior to that show, they knew almost nothing beyond Anne Frank’s diary.

“Not to disparage the diary of Anne Frank,” Jonathan Brent, YIVO’s executive director and CEO, told JNS. “Her experience was her experience in Holland in an upper-middle-class family, and it wasn’t the same as a 13-year-old girl who was born in Vilna, Poland under the conditions of Polish and Lithuanian antisemitism.”

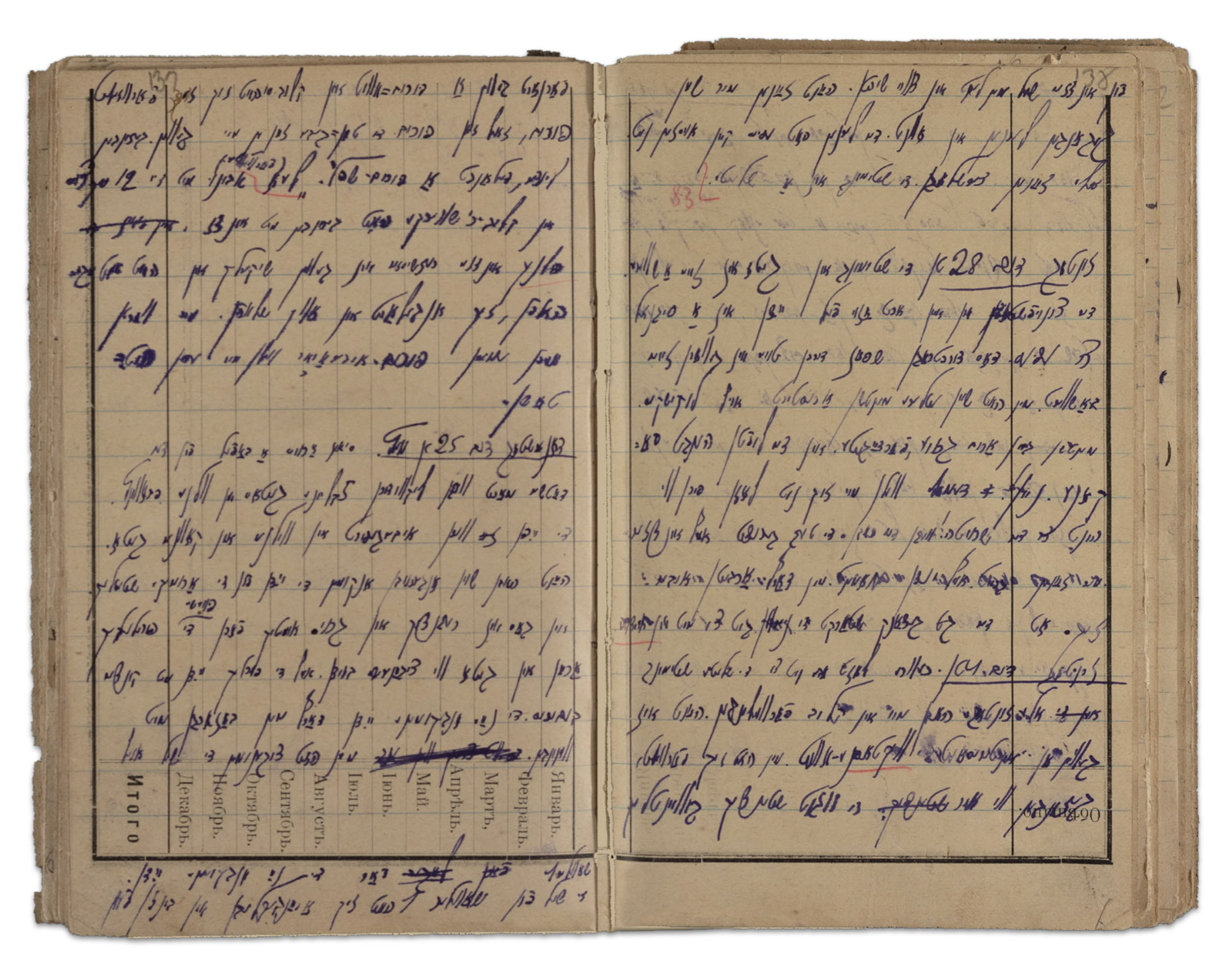

A new YIVO online exhibit focuses on another diary of a teenager in Vilna—Yitskhok Rudashevski, a 13-year-old boy, who documented his days in that city’s ghetto. “Yitskhok Rudashevski: A Teenager’s Account of Life and Death in the Vilna Ghetto” opens online on July 17.

The 13-year-old “found himself faced with the utmost brutality of the world,” Brent told JNS. “It is right in his face. It was not in Anne Frank’s face.”

“Anne Frank is writing her diary through the anxiety-filled seclusion of her hiding place,” he said. “But she is not witnessing what is going on in the streets” of the ghetto in Vilnius, the modern-day capital of Lithuania that was then part of Polish territory between the two World Wars.

Rudashevski’s diary captures not only the disintegration of Jewish society in the ghetto but also “the restoration of Jewish culture that he is able to find,” Brent said.

That took place via smuggled Jewish cultural items, including a library of books, saved by the Paper Brigade, a collective of writers and intellectuals who were slave laborers in Vilna and rescued Judaica and books from Nazi theft and destruction.

Cultural resistance to evil

In 1943, the Nazis murdered Rudashevski, then 15, among thousands of other Jews in the Ponary massacre.

Although the young boy did not get to read the great writers of his time, “he came up, himself, with the idea of cultural resistance to evil, and that the way to resist this brutality, the way to resist this evil, was by aligning himself with the continuity of Jewish culture,” Brent said.

The boy found that Jewish culture in the works of the Yiddish poet Avraham Sutzkever and volumes that the Paper Brigade made available to him.

The online YIVO exhibit tells Rudashevski’s story from beginning to end, through his eyes and words, connecting his short life to the major events occurring around him in the ghetto and worldwide.

The impersonal nature of the boy’s diary adds to its historical value, according to

Karolina Ziulkoski, chief curator of YIVO’s online museum. (YIVO owns the original diary.)

“He was talking more about what was going on around him, as opposed to his feelings,” Ziulkoski said. “This is something that is very specific to Rudashevski.”

Many diaries of the time focused on the diarist’s feelings and perception of what was happening nearby. “His was more like—this is how, this is what, this is how I see what is going on—but not how he feels,” the curator told JNS.

‘The way that people lived’

Alexandra Zapruder, a scholar and editor who co-curated the Rudashevski exhibit, told JNS that the story is too meaningful to remain so unknown.

“Genocide is not something that happens to one person. It happens to millions of people, and when we are reductive about the story, there’s a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of this particular crime,” Zapruder said.

She “fell in love with this diary,” which she has taught for many years, and always wanted to see “something done with it,” whether a new translation or edition.

“I thought, well, YIVO has all these materials, and it would be great to do something more with it,’ she told JNS.

In 1944, Rudashevski’s cousin Sarah Voloshin—who was the sole survivor of her nearly 50 family members—discovered the diary. The YIVO show details that development and tells Rudashevski’s story through a variety of digitized artifacts, from the ghetto’s list of residents and correspondence between Jewish refugees to maps, police reports, strike notices and children’s essays.

It details excruciating moral choices that Rudashevski and his contemporaries had to make, using the diary excerpts as an entry point and follows a path from pre-war Poland to developments around the globe that set the stage for the Holocaust. The exhibit uses animation, graphic novels, video dramatizations and other interactive features to illustrate that story.

It also explores what was happening specifically in the Vilna ghetto, with Rudashevsky playing a leading role.

The teenager’s mother kept the family alive by working as a seamstress, and his father had worked as a typesetter for the Yiddish newspaper Vilner Tog, tying father and son to the intellectual life of the ghetto.

With only time on their hands due to the Nazi’s restrictions, the men organized a cultural life, setting up study groups, exhibitions, lectures and libraries, all of which could only occur during the so-called quiet periods, when the Germans weren’t cleansing the ghetto of people to murder at Ponar.

“We tend to think about gas chambers and Auschwitz and piles of dead bodies, and we have this image of the way that people died,” Zapruder said. “We don’t always have access to the way that people lived while they were in these circumstances.”

“How they tried to maintain their humanity, what the effect was of this suffering and persecution on their relationships, on their dreams, their plans, their understanding of their own humanity, their faith and thoughts—this diary delves into all of those things,” she added.

Rudashavsky and his friends found ways through cultural and spiritual means, “through creativity, through intellectual pursuits, through hard work, to resist that stagnation, to resist the terms that were being imposed” on them, she said.

Brent told JNS the show’s message is particularly important for U.S. Jews, many of whom don’t know much about the history of the Vilna ghetto.

Rudashevsky makes clear that “the spirit of our youth will go forward and is unstoppable,” Brent said.

“When you read that, you realize that he is just the medium through which the spirit that is contained in that culture is flowing,” he added. “It did survive. It did transcend him.”

Brent returned recently from a trip to Poland and Lithuania with a group of successful, older Jews who had achieved the American dream. They told him that they had a sense of something missing in themselves, which prompted them to make the trip.

That feeling goes to the heart of Rudashevsky’s story and why it is so important, according to Brent.

“This cultural continuum that Rudashevsky finds gives him the kind of peace of mind and inner strength that was necessary for him to retain his self worth, to retain his understanding of himself as a Jew,” Brent told JNS.

“If you are deprived of that culture, you then also deprive yourself of that inner strength,” he added. “You have a strong Jewish people only if you have knowledge, only if you feel this continuity, that you are not alone in the world.”