The San Diego Symphony, like many other orchestras throughout the world, is honoring the centennial birthday of Leonard Bernstein, the great 20th century American conductor, composer, pianist and educator, by including his works in all three Masterworks symphony programs during the month of May, as well as in a chamber music evening.

On May 4, 5 and 6, under the direction of the young French conductor, Fabien Gabel, Music Director of the Quebec Orchestra, the San Diego Symphony will open with Bernstein’s Three Dance Variations from the ballet, Fancy Free.

Violinist Simone Lansme will perform Bernstein’s Serenade, inspired by Plato’s Symposium. Other works on the program are by R. Strauss and Offenbach.

On May 8, a chamber music evening will open with Bernstein’s Clarinet Sonata, performed by Principal Clarinetist Cheryl Renk and Pianist Orli Shaham. Also scheduled are works by Adams, Chopin and Beethoven.

May 11, 12 and 13, Jahja Ling, Conductor Emeritus of the San Diego Symphony, will return to conduct a concert featuring Bernstein’s Symphony #1, Jeremiah, which the composer wrote when he was 24 years old.

Jahja served as an assistant to Bernstein for several seasons and considers him one of his mentors. That concert will also include works by Beethoven and and Barber.

The final Masterworks symphony concert of the season, with Edo de Waart on the podium, will open with Bernstein’s brief, but impressive Overture to Candide, Bernstein’s quintessential curtain-raiser. As a member of the San Diego Symphony for 37 years, I could not count how many times we played this snappy, upbeat piece, which always brings rousing cheers from the audience. Once, I recall hearing the famous klezmer clarinetist, Giora Feidman, rendering a klezmer version of the overture as a clarinet solo.

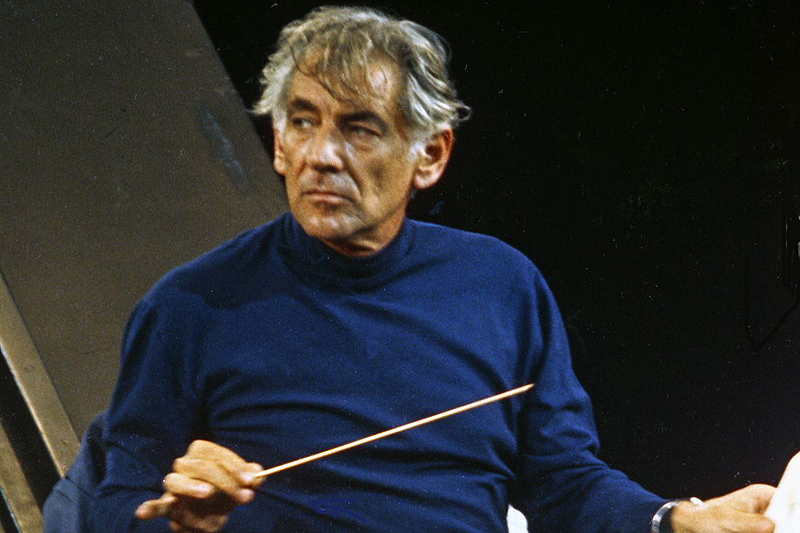

I have been a fan of Leonard Bernstein since I had thepleasure of playing two concerts under his direction at the Berkshire Music Festival at Tanglewood during the summer of 1950.I recall his jovial personality, his collegiality with themusicians and, most of all, his energetic, inspiring conducting.

He moved around more than other conductors, literally dancing on the podium, but, I recall, every motion, even the bending of his pinkie finger, had musical meaning and conveyed a musical message. I never heard a more spirited performance of Ravel’s La Valse

than what he drew from our orchestra of youngmusicians. Another work on that program was Copland’s El Salon Mexico, with all of its tricky rhythms. The second concert under his direction was an All-Bach Program as part of the celebration of 200 years since

Bach’s death. There was a concerto for two pianos and a concerto for three pianos in which he participated as both conductor and performer.

I recall how he joked with the musicians, and used Yiddishisms, even though many of the musicians were not Jewish. “If you don’t understand, ask your neighbor,” he laughingly advised. He felt very comfortable in his Jewishness. When it was suggested to him by Koussevitzky that he change his name to something less Jewish sounding, he adamantly refused.

He was a great supporter of Israel, especially the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. He was their permanent guest conductor. When there were impending hostilities and other conductors would cancel, Lenny often came to the rescue. There were memorable concerts for the troops and at the amphitheater on Mt. Scopus, as well as in the Mann Auditorium in Tel Aviv.

During the months following my summer in Tanglewood, Serge Koussevitsky became ill and the first American tour of the Israel Philharmonic, which he was to conduct with Bernstein, fell totally on the shoulders of Lenny.

I recall going backstage in Los Angeles after their concert to greet Lenny and remind him that I played under him that previous summer. Although he was cordial, as a violinist sitting in the section, he did not remember me.

I thrilled to the movie version of his West Side Story. I thoroughly enjoyed the JCompany performance several years ago with Rebecca Penner in the lead, under the direction of the phenomenal Joey Landwehr.

Last February, I attended the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s remarkable performance of Bernstein’s Mass, the eclectic work with singers and dancers, written in memory of John Kennedy.

When the Israel Philharmonic was here several years ago, under the direction of guest conductor Dudamel, the first half of the program was devoted to Bernstein’s work, including the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story and Halil for solo flute and orchestra, the last piece he wrote.

One of the most impressive theater pieces about Leonard Bernstein was Hershey Felder’s Maestro, most recently staged at the Lyceum Theater.

Leonard Bernstein is, indeed, an American icon. His enormous talent, channeled in multiple directions, enriched the lives of all who experienced him. He is regarded as the greatest American musician of the 20th Century.

He is worthy of celebration by our San Diego Symphony Orchestra and by the music lovers of the world.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World