The exhibition “Being and Belonging,” on view through Jan. 7 at the Royal Ontario Museum, features artworks by contemporary women artists “from the Islamic world and beyond,” per the museum website, which hails the show as a “bold” exploration of “the defining issues of our time.”

“Deftly interrogating themes of identity, power, sexuality and home, this exhibition resists simple stereotypes with outstanding artworks from both emerging and well-established artists,” according to the museum, which issued a “trigger warning” about “violence, war, persecution, survival, innovation and joy. A few artworks contain nudity.”

The nearly 110-year-old museum—Canada’s “largest and most comprehensive,” housing 13 million objects—did not warn visitors that labels in the exhibition can also contain anti-Israel language.

‘Implies Israel is the culprit’

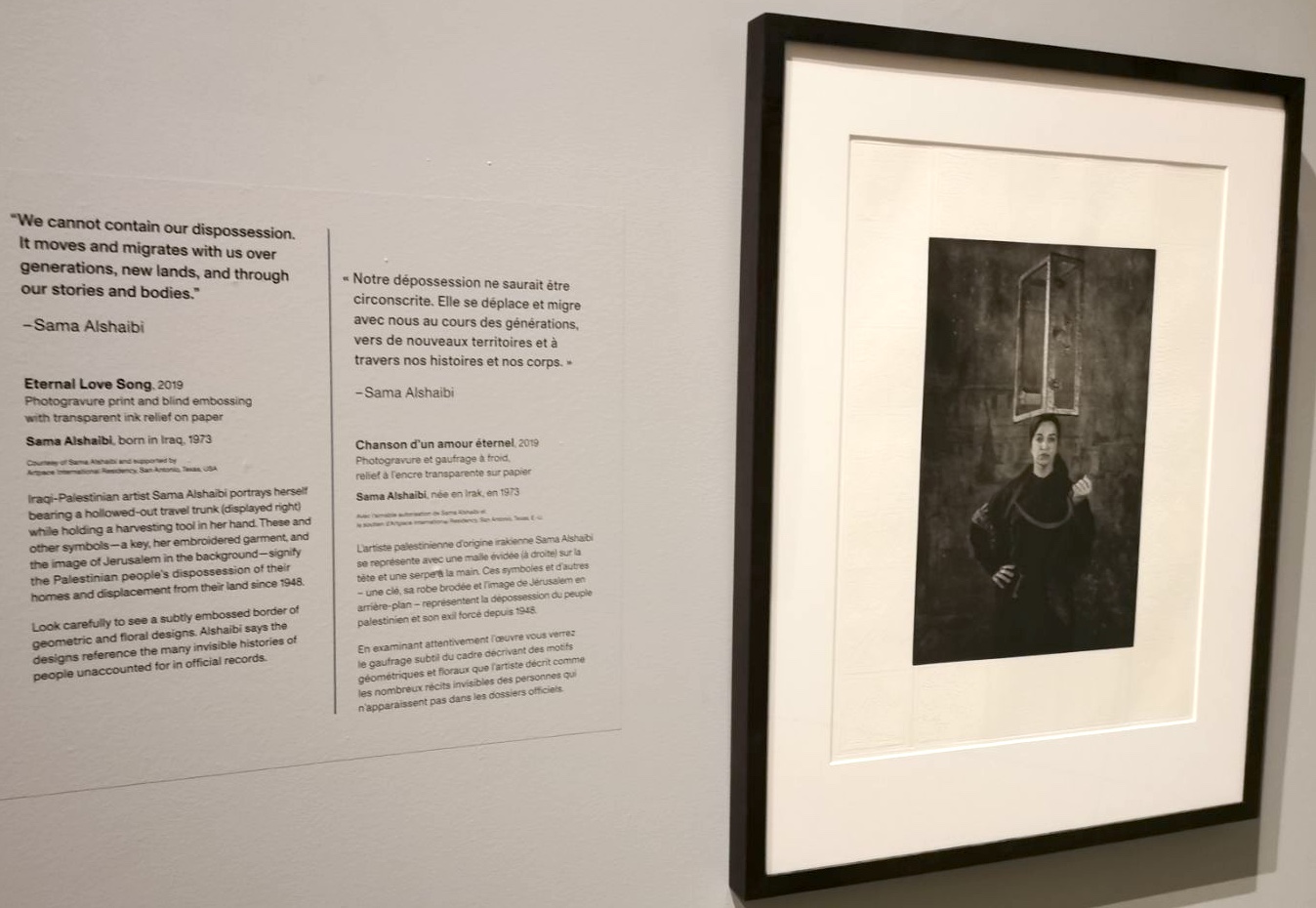

“We cannot contain our dispossession,” reads a quote from Iraqi-American artist Sama Alshaibi in a wall text in the exhibition, alongside the artist’s 2019 photo print titled Eternal Love Song. (Alshaibi is also an art professor at the University of Arizona, where she co-directs a Racial Justice Studio.)

“It moves and migrates with us over generations, new lands and through our stories and bodies,” the museum’s label adds. It notes that Alshaibi has a “hollowed-out travel trunk” on her head, and she holds a sickle (“a harvesting tool”).

“These and other symbols—a key, her embroidered garment and the image of Jerusalem in the background—signify the Palestinian people’s dispossession of their homes and displacement from their lands since 1948,” the wall text states.

“The artwork, and its accompanying information at the museum, while not mentioning Israel, provides no historical context and tacitly implies that Israel is the culprit,” HonestReporting Canada noted in an Oct. 2 email. (The University of Arizona’s web page for Alshaibi also notes “dispossession” and “dislocation” without mentioning Israel. It notes she was “born in Basra to an Iraqi father and Palestinian mother.”)

“In reality, Arab leaders throughout the Middle East, along with Arabs living in pre-state Israel, were actively encouraging members of their community to flee from the path of marauding Arab armies following Israel’s independence in 1948,” the email added.

In a Sept. 29 alert, HonestReporting Canada cited another work of Alshaibi’s in the show, titled An Act of Possession, which “portrays a hollowed-out suitcase made of aluminum, plywood and paper.”

The exhibition refers to that sculpture as a “symbol of forced migration” and a quote from the artist states that the trunk “was made in 1948, the year my mother went from simply being a young girl to becoming a Palestinian refugee without the right to return to her homeland.”

“I want my actual homeland, not the multi-generational inheritance of dispossession,” reads another quote from the artist in the show.

“While art is certainly an intensely subjective endeavor, history is another matter, and Alshaibi’s description of her family’s history, as well as the ROM’s official description of what took place in 1948, is at best highly misleading, and at worst outright disinformation,” HonestReporting Canada stated.

“The Royal Ontario Museum, both as a recipient of a significant amount of tax dollars, but also as a leading institution of cultural artifacts, has the ability to share personal stories in powerful ways, but this does not exempt it of its responsibility to adhere to the facts, requiring the institution to curate content objectively,” it added.

‘We are a learning institution’

On Oct. 3, Josh Basseches, director and CEO of the Royal Ontario Museum, wrote to HonestReporting Canada stating that the museum “is a learning institution, and we listen.”

After noting that HonestReporting Canada had focused on two works of art by one artist, from more than 100 works by 25 artists in the show, Basseches claimed that the media watchdog was wrong to say that the statements on the exhibition walls were the museum’s “official description” rather than the artist’s personal statements. (Overwhelmingly, curators write the labels for museum exhibitions, rather than artists explaining the significance of their own works.)

“Israel and the Middle East in 1948 are not the subject of the show,” the museum executive wrote. Still, Basseches said the museum was going to make changes.

“While the artist’s narrative reflects her own experience expressed through art, we recognize that it is one artist’s view related to a historical topic for which there are various lived experiences and narratives,” he wrote.

In response to the HonestReporting Canada alert, the museum is revising the text associated with Alshaibi’s art “to be more precise” and “to make it clear that the text label describes the artist’s own point of view,” Basseches wrote.

The museum, he added, is revising the opening panel to the exhibit “to underscore that these are the perspectives of the artists, and to encourage audiences to further explore the topics presented in the exhibition on their own for a deeper and more contextualized understanding of the subjects, beyond what is included in the exhibition.”

Other text panels in the exhibit will refer back to the new opening panel text, Basseches added.

“The Royal Ontario Museum is one of the most prominent and influential museums in North America, attracting huge numbers of annual visitors to its exhibits. That is precisely why it was so important for the label to be amended, and why its decision to revise the description is so welcome,” Mike Fegelman, executive director of HonestReporting Canada, told JNS.

“When dealing with history, particularly surrounding Israel’s independence in 1948, which is the target of so much misinformation, extra care is needed to be factual,” Fegelman added. “We are very pleased that the ROM will be making these changes.”