“Today, Theodor Herzl is best known for his beard, not his books,” laments Gil Troy, editor of “The Zionist Writings of Theodor Herzl,” in his introductory essay to a new edition of Herzl’s diaries.

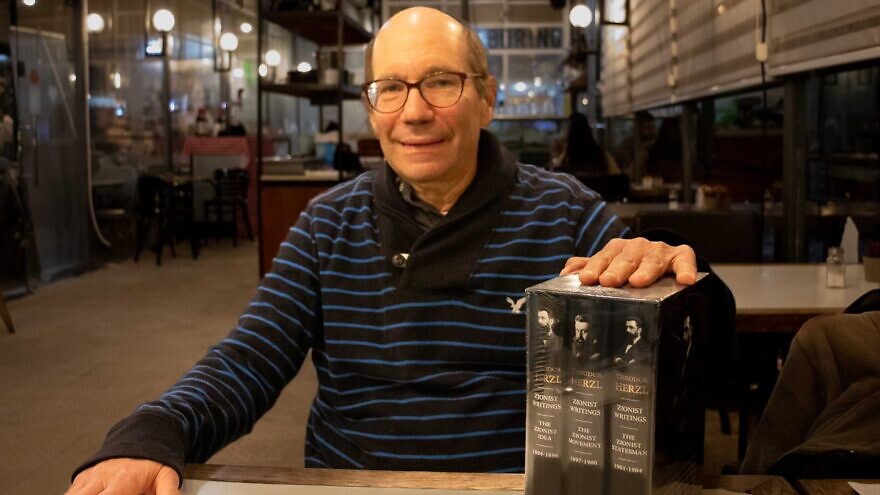

Troy, a professor of history at Canada’s McGill University now living in Israel, wants to make Zionism’s founders come alive for the next generation. His latest effort is a three-volume collection of Herzl’s writings.

“The Zionist Writings” are the first titles in that ambitious effort. They include a fairly comprehensive collection of Herzl’s diaries and other works, including his play “The New Ghetto” (1894), of which Herzl biographer Alex Bein said, “Herzl completed his inner return to his people”; Herzl’s 1896 manifesto “The Jewish State“; and important essays, like “The Menorah“ (1897), showing how, through Zionism, Herzl reconnected with his Judaism.

The series uses translations from the original German made by historian Harry Zohn in the 1960s. Other works, like “The New Ghetto,” are newly translated by Uri Bollag.

“It’s an attempt to invite the Jewish people to build a bookshelf, because we’ve been building a bookshelf for thousands of years, but most of us don’t know the Jewish texts, the Jewish canon,” he said.

Troy sees no better place to start than Herzl. “He’s our George Washington and our Thomas Jefferson all wrapped in one,” said Troy. “Washington’s diaries are interesting, but they’re not ideological. That’s why, when talking about Herzl in American terms, we say he’s a cross between Washington and Jefferson, because he’s also a conceptualizer.”

Troy, who pored through 2,700 pages of Herzl’s diaries, described them as “a political-science version of an artist’s sketchbook.”

“Herzl draws in the contours of the Jewish state. He plans different dimensions from a flag to the architectural aesthetic, from labor-capital relations to the dynamics between rabbis and politicians,” Troy writes in one essay.

The series is organized chronologically. Troy wrote 11 introductions, one for each year Herzl was active as a Zionist (he died at 44 having suffered for years from a weak heart). Dividing by years can be artificial, but not in Herzl’s case, Troy said, noting important yearly milestones in Herzl’s development as a thinker and a leader.

Herzl, an assimilated European Jew, concluded through experience and observation that the only solution to the Jewish problem was a Jewish state. “Let them give us sovereignty over a portion of the globe that is large enough for our just national needs, and we will take care of everything else,” he said.

The process to reach that conclusion was gradual—13 years by Herzl’s own estimate. “Just as the Jew-haters started seeing various unappealing traits as endemic to the Jewish character, Herzl started seeing Jew-hatred as endemic to the European character,” Troy wrote.

When the idea of a Jewish state finally did spring upon him, it was like a thunderbolt. “I have the solution to the Jewish question,” Herzl wrote while working on his manifesto. “I know it sounds mad; and at the beginning I shall be called mad more than once—until the truth of what I am saying is recognized in all its shattering force.”

A talented journalist and playwright, he possessed a unique set of gifts—showman, statesman, prophet and political thinker—that propelled him to the head of the Zionist movement, which existed prior to Herzl but in scattered form. Herzl termed Zionism “the Jewish people on the march.”

Herzl not only wrote the manifesto for a Jewish state but started the Jews on the path to building one, meeting world leaders and creating key institutions, including a Zionist congress, a newspaper—Die Welt, or “The World”—for disseminating Zionist ideas, and a Jewish Colonial Bank to raise the funds necessary for settling the Land of Israel.

While Herzl endured enormous obstacles and setbacks in pursuing his course, he maintained a remarkable surety of eventual success. The diaries are a testament to that certainty, which he begins in 1895 to chronicle his Zionist activities. “What dreams, thoughts, letters, meetings, actions I shall have to live through—disappointments if nothing comes of it, terrible struggles if things work out. All that must be recorded.”

Herzl believed that a Jewish state was “a world necessity—and that is why it will come into being.” When Herzl passed away on July 3, 1904, his will directed that he be buried in Vienna next to his father “until the Jewish people will carry my remains to Palestine.”

Q: What attracted you to this project?

Troy: One of the things I’ve also been working on is what I call “identity Zionism.” Herzl focused on political Zionism, an outer Zionism, which was all about establishing the state. … If political Zionism was all about establishing the state, identity Zionism is about building our core sense of self. Many of the core texts talk not just about an outer Zion but an inner Zion as well.

[Ed. note: Herzl himself touched on this inner Zionism, writing in 1895: “No one ever thought of looking for the Promised Land where it actually is—and yet it lies so near … This is where it is: within ourselves!” Similarly, in a speech in 1896 he talks about an inner transformation through the struggle for an outer Zionism. “I do know that even by merely walking along this road we will become different persons. We shall thereby regain our lost inner wholeness and along with a little character—our own character, not a Marrano-like, borrowed, untruthful character, but our own.”]

As the volunteer educational chair of Birthright Israel, I find that what young people are missing most are things like identity, connection, community.

Herzl himself was kind of lost, traumatized. He felt cut off because he was being robbed of all the dreams that he’d bought into to be a proper European. The Jewish people were being robbed. And all of a sudden, he said, “I want something else.” If you look at his journey, one of the exciting things about the diaries is that it’s not a snapshot, it’s a continuous, moving, motion picture. You see his evolution. He discovers bit by bit that Judaism is not just a dead ancestral force. It’s not just this defensive thing that we’ve been tied to by our common enemies. It’s something positive.

He has this beautiful story called “The Menorah.” A year before, when he just started getting involved in Jewish issues, he was at home lighting his Christmas tree candles when the chief rabbi of Vienna walks in. He’s not embarrassed; the chief rabbi of Vienna is embarrassed. The next year, he writes this story about a man who was cut off from his past, who paid the price for being Jewish but didn’t appreciate its greatness. The man decides to buy a Menorah. …

The first night he lights two candles, and there’s a little bit of light in the house. And each night, he lights another candle, and another candle, and more and more light comes into the house. And by the end, the house is ablaze with glory. And he realized that this is the journey that he’s on, and that he’s taking the Jewish people on. We all know that you’re supposed to put your Menorah on the outside, but also you see it from the inside. That’s identity Zionism. Political Zionism is the external Zionism. It says, “We are people who have a right to a state of our own.” But it’s also that inner light that says, in a world which eviscerates community, in a world that robs us of meaning and a world that robs us of connection, we’re going to have this inner light and it’s going to be a light that we share.

Q: What is the state of Zionist education today?

A: The only Zionism they’ve heard about in the States is the one that’s being targeted; it’s defensive and about Israel advocacy. In Israel, Zionism’s been mummified. It’s something you need to know to pass your matriculation exams—explain why this street is named Jabotinsky, or that one after Ahad Ha’am. But they don’t look at Jabotinsky or Ahad Ha’am, or any of the others, as if they were alive today with ideas that are still relevant. Many young people, when you actually speak to them about Zionism as something alive, something dynamic, something relevant for today, get very excited.

Q: Why is it that of the two most important events relating to the Jewish people in the last century—the Holocaust and the creation of Israel—only one is studied while the other is virtually ignored?

A: I think the short answer is we’re a traumatized people. The scale of the death, the scale of the suffering, is something that the human mind is still struggling with. So I understand it on one level, but I agree—we are so addicted to the negative, and who wants to join that?

I remember when I was in university. I didn’t understand why the Holocaust courses would get 400 people and you could barely fill a classroom with anybody interested in learning about the State of Israel. And we’re seeing it right now. We’re building up to the 75th anniversary of the State of Israel and I’m not feeling the excitement. I’m not feeling the love. I’ve read a number of articles about this, challenging philanthropists and statesmen and Hollywood to start preparing for the 75th. This is an opportunity to frame Israel outside the politics and partisanship. Here’s an opportunity to celebrate the achievements of Israel.

And I’m well aware when I’m calling for Hollywood where they stand and how uncomfortable they’ll be, but I can’t imagine a greater opportunity. … Unfortunately, American Jews aren’t thinking that way, and I don’t think enough people here in Israel are thinking that way either: what do we do for the 75th?

Q: What would Herzl say if he could see Israel today?

A: He would be amazed. To think of that confession he scribbled to dear diary, embarrassingly, after the Zionist Congress, that 50 years from now the world will see that we established the Jewish state in this little Zionist Congress. People say he was off by one, but actually 50 years and three months later the United Nations signed off on this extraordinary thing. So I think he would say, “Wow, it really worked.” True, there would be disappointment; he did think antisemitism would disappear. He also expected the exile, the Diaspora, to disappear. So he bet big on certain things that turned out to be wrong. But on the whole, he would be shocked at how well he did.

Q: What are you working on next?

A: I’m starting this initiative with Gefen Publishing to write a series of children’s books, for 12-to-14-year-olds, pivoted around choice. So the first one was Theodor’s choice, that big moment when he decides to join the Jewish people. I’m now writing about David Ben-Gurion, which is much harder, because Herzl has those 11 years and it’s one choice. Ben-Gurion has a series of choices. I think within a couple of months we’ll have that first book out.