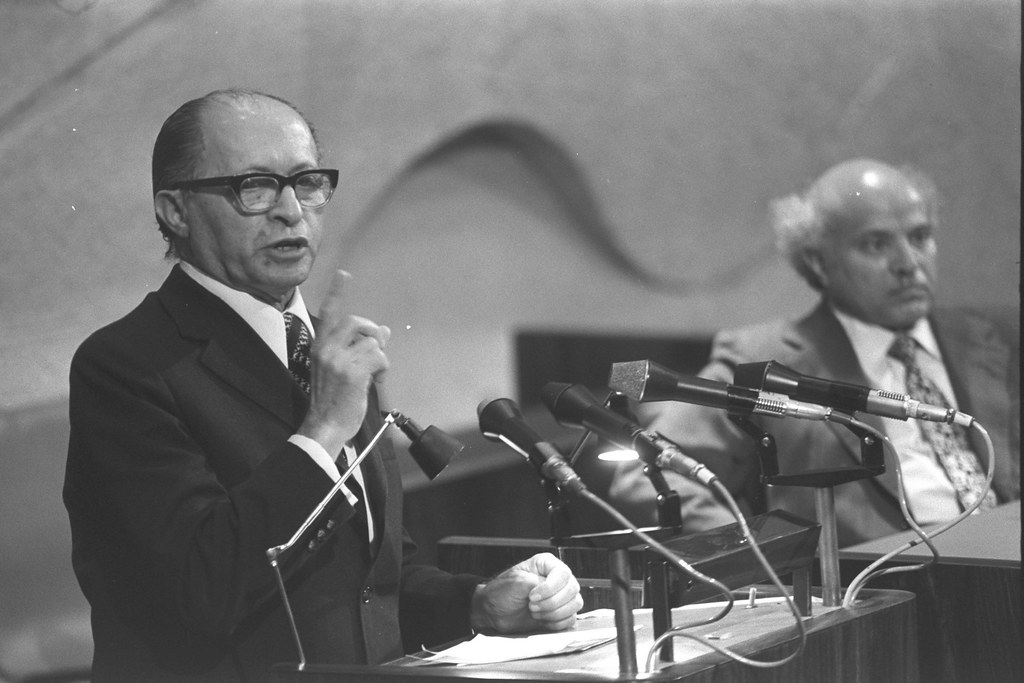

On December 10th, 1978, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin received the Nobel Peace Prize for signing the Camp David Accords with Egypt. In his Nobel lecture, Begin made the point that peace is a foundation of Judaism.

“The ancient Jewish people gave the world the vision of eternal peace, of universal disarmament, of abolishing the teaching and learning of war,” he said. “Two prophets, Yeshayahu Ben Amotz and Micha HaMorashti, having foreseen the spiritual unity of man under God—with His word coming forth from Jerusalem—gave the nations of the world the following vision expressed in identical terms: ‘And they shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation shall not lift up sword against nation; neither shall they learn war any more.”

Begin’s lesson has deep biblical roots. While the Jews in the desert made military preparations to enter the Land of Israel, they were commanded to first offer negotiations: “When you march up to attack a city, make its people an offer of peace.” It is a mitzvah to search for peace before going to war.

Ramban and Rambam explain that this obligation included the initial war of conquest. They quote a passage from the Talmud Yerushalmi that says that Yehoshua sent letters offering peace to the inhabitants of Canaan before crossing the Jordan River. Rashi, however, disagrees, and explains that the biblical command to offer peace is limited to elective wars that would take place later in history.

At first glance, Rashi seems to limit the obligation to seek peace. But a look at all of Rashi’s writing on this subject offers a very different picture. He is actually making a far more dramatic claim about peace.

In our Torah reading, when the Jews approach the boundaries of Sichon the King of the Amorites, Moshe sends messengers with “words of peace,” looking for a way to avoid war. This request is difficult to explain according to Rashi’s view. The war against Emorites was a war of conquest, and there should have been no obligation to make an offer of peace. So why did Moshe send these messengers?

Rashi explains that Moshe thought, “Although the Omnipresent had not commanded me to proclaim peace unto Sihon, I learnt to do so from … when the Holy One, blessed be He, was about to give the Torah to Israel, he took it round to Esau and Ishmael … and opened unto them with peace. Another explanation … Moshe said to God, ‘I learned this from You. … You could have sent one flash of lightning to consume the Egyptians, but instead, with much patience, You sent me from the desert to Pharaoh saying, Let my people go.’”

At Mount Sinai, God reaches out to all of humanity, not just Israel; and in Pharaoh’s court, God follows paths of pleasantness. Clearly, His ways are the ways of peace.

Without any divine command, Moshe decides on his own to pursue peace with Sichon. He does so because we don’t need to be commanded to pursue peace; we should understand the importance of peace on our own. Peace is not just another halachic obligation; it is a moral foundation of Judaism. Even when we aren’t obligated to make peace, we want to make peace. Rashi is offering an even more radical view, obligating one to pursue peace even without a command.

One could stop here. Peace is often the subject of edifying lectures and inspirational sermons. But in the real world, the pursuit of peace is far from simple. The willingness to extend goodwill to one’s enemies can lead to failure. Moral scruples, including the willingness to make peace, are often a strategic disadvantage. There is an asymmetry when the moral and immoral engage in battle, because ethics on the battlefield can be exploited as a weakness.

The ruthless can misuse diplomacy and negotiations in order to buy time, and barbarians have no limits on how they conduct war. They see cruelty as a source of strength. Indeed, authoritarians and fanatics often mock those who desire peace. Ismail Haniyah, the former Hamas prime minister of Gaza, would often proclaim: “We shall (be) … educating the future generation to love death … as much as our enemies love life.” This refrain has been repeated by many others. To love life and pursue peace is seen as unmanly and cowardly, a weakness born out of decadence.

This reality makes war far more complicated for those who pursue goodness and peace. One must be shrewd with the devious (II Samuel 22:27). It would be disastrous for the nice guys to always finish last. But how shrewd may one be? Michael Walzer, in his book Just and Unjust Wars, describes what he calls the “realist argument”—that all is fair in war, because wars are fought to be won. Even in Western democracies, there have always been those who dismiss or diminish the need to consider battlefield ethics. They believe that the ends justify the means, and that the noble goal of defending democracy justifies the most ignoble of methods.

And there have always been moments of necessity when realism is the only reasonable option. In the last century, atomic bombs were dropped on Japan to end what seemed to be an endless war and prevent even more lives from being lost. During the Cold War, the democracies of the world adopted the policy of mutually assured destruction. They vowed to retaliate fully against any Soviet nuclear attack, even if the response would be pointless and too late to save their own countries. Mutually assured destruction, if employed, would be an act of vengeful retaliation, but in an era of nuclear brinkmanship, it was a critical deterrent. This policy was a matter of necessity because, without it, militant dictatorships like the Soviet Union could simply take over the world.

One might conclude that, if war by its very nature requires realism, then dreams of peace and ethical concerns can be ignored. But even on the battlefield, one must still place ethical concerns first. The Talmud Yerushalmi says that when besieging an enemy city, there is a commandment to leave a path open for people to flee. The Ramban explains that the reason for this commandment is because we must “learn to always act with compassion, and even (show compassion) to our enemies during battle.” An army must act in a humane manner, even if it is inconvenient. Going into battle is not a vacation from ethics.

Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein said, “The most important thing that a person going into battle must know is that he is not passing from a world with a hierarchy of values to a world with a different hierarchy of values. One person, one nation, cannot split into two. And in every situation, on top of the hierarchy of values must stand peace.” A religious tradition that takes ethics seriously will not abandon its values during wartime.

This idea is referred to as “just war,” but the question of how to define an army’s ethical obligations during wartime is often difficult. Walzer quotes Thomas Nagel, who in an essay entitled “War and Massacre” describes an ongoing problem in assessing wartime ethics, one of “means and ends.”

On the one hand there is a utilitarian perspective, for which the path to the quickest victory is what is most important. This is an argument of the ends justifying the means. On the other hand is the absolutist perspective, which focuses not on outcomes but actions, and is concerned with avoiding any morally distasteful behavior.

These two perspectives are frequently in conflict, and even those who care deeply about ethics recognize that there are no simple solutions to battlefield questions. As Walzer puts it, “We know that there are some outcomes that must be avoided at all costs, and we know that there are some costs that can never rightly be paid.” But in between those extremes, answers become far less certain.

Pursuing ethics in wartime is like trying to ride two horses simultaneously, endeavoring to fulfill the duty to protect one’s country while never letting go of the obligation to treat all human beings with compassion. This is sometimes impossible. Walzer acknowledges that “decent men and women, hard-pressed in war, must sometimes do terrible things, and then they themselves have to look for some way to reaffirm the values they have overthrown.” Ethical standards, even when breached, must continue to be honored.

In the real world, it often seems futile to pursue peace, and naive to offer enemies compassion. But we must continue to do so because it is a fundamental value. A well-known Midrash lists multiple ways in which the Torah emphasizes the great importance of peace. The list is quite varied, and the examples of Torah-ordained “peace” relate to very different conflicts: friends, relatives, warring countries and even the angels above. In it, the personal and geopolitical are all thrown into the same pot. Fighting with your spouse and waging war with an enemy are listed one after the other, as if the situations are somehow comparable. But I believe the point of the Midrash is precisely that: Peace is always important, at home and abroad, in heaven and on earth. We never stop caring about peace, no matter how big or how small, because we see the world through peace-colored glasses.

The Jewish tradition’s reverence for peace is reflected in Israel’s Declaration of Independence. In it, Israel makes a remarkable offer to its neighbors: “We extend our hand to all neighboring states and their peoples in an offer of peace and good neighborliness, and appeal to them to establish bonds of cooperation and mutual help. … The State of Israel is prepared to do its share in a common effort for the advancement of the entire Middle East.”

In 1948, Israel’s call for peace seemed futile. Immediately after declaring independence, Israel was invaded by seven neighboring Arab countries. But 74 years later, this declaration looks prophetic. Israel now has peace treaties with most of its neighbors. Maybe the dream of peace isn’t that naive. After all, Moshe’s call for peace was finally answered, 3,300 years later.

Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz is the Senior Rabbi of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun in New York.

This article was originally published by the Jewish Journal.