By the autumn of 1942, trains had carried 2,289 Jewish men, women and children from the French Rivesaltes concentration camp northwards to Drancy.

By the autumn of 1942, trains had carried 2,289 Jewish men, women and children from the French Rivesaltes concentration camp northwards to Drancy.

But not all Jews that were held at the Rivesaltes camp perished in the Holocaust. Eighty-four percent of the children staying at the camp escaped deportation, primarily thanks to Mary Elmes, an Irish woman working for a Quaker aid organization called the American Friends Service Committee.

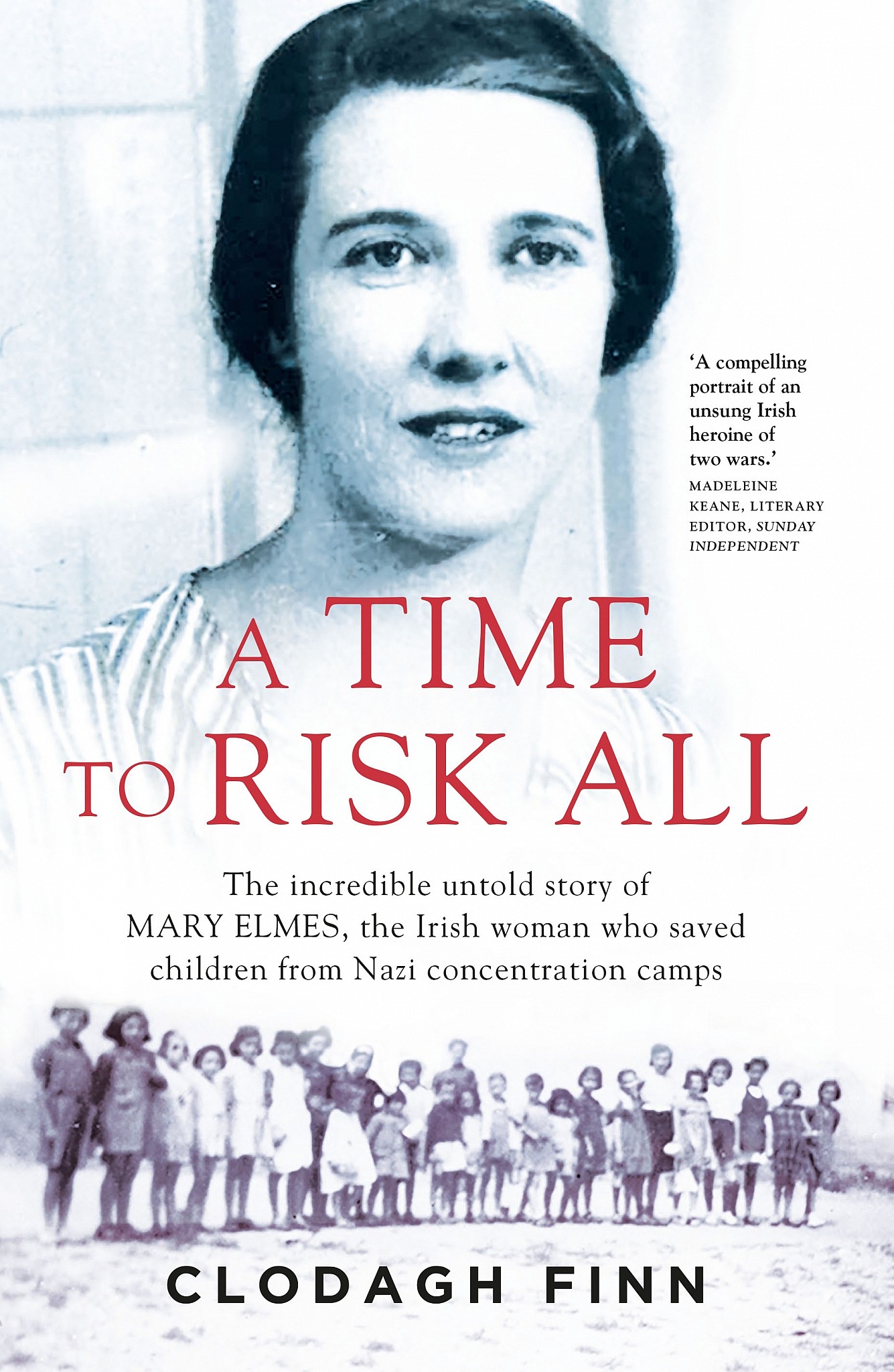

Elmes’ brave wartime efforts to save hundreds of Jewish children at the Rivesaltes camp is the central theme of a recently published book called “A Time To Risk All” by Irish freelance journalist, Clodagh Finn.

Elmes had worked as a humanitarian volunteer during the Spanish Civil War. Then, when World War II broke out, she moved on to continue to work where conflict arose.

On June 22, 1940 the Franco-German Armistice divided France in two parts: Paris and the northern region, which comprised the German-controlled Occupied Zone, and the Unoccupied Zone in the south, which was run from the town of Vichy by the staunchly anti-Semitic Marshal Philippe Pétain.

Drancy, located in a Parisian suburb, would see almost 70,000 Jews deported to the east between 1942 and 1944. In the Unoccupied Zone, Rivesaltes would become the most prominent holding center for Jews.

The Rivesaltes concentration camp, Finn explains, was officially named Camp Joffre. It was initially built in 1938 as a military barracks to house troops in transit. The idea of using the camp as a place to intern refugees began to gain traction in November 1940.

By November of the following year it opened its doors. “During the Spanish Civil War, about 500,000 Spanish people came over the border to France, so the French authorities set up Rivesaltes to house these so-called ‘undesirable’ Republicans,” says Finn. “Then when WWII broke out, 8 million people started to come down from the north: Germans, Belgians, and then, increasingly, Jews.”

“Rivesaltes was the sorting center in the south of France [for Jews],” she says. “[A kind of] Drancy of the south of France. The journey [towards] genocide was beginning here for Jews. But Rivesaltes was also the camp where the most rescues took place.”

Quakers to the rescue?

Finn explains that there were two ways that Mary Elmes and her colleagues tried to get Jewish children out of Rivesaltes camp.

“She set up a number of children’s colonies around the picturesque districts of Pyrénées-Orientales, in the southwest of France,” she says.

“There were also convoys of refugees going to the United States. This was organized by the Quakers, and also by Eleanor Roosevelt. So both activities were legitimate ways to get children out of Rivesaltes,” Finn says.

The latter scheme was an agreement facilitated by the Quakers’ executive secretary, Clarence Pickett, who set up an organization called the United States Committee for the Care of European Children.

It brought more than a thousand Jewish children to America from both France and Britain. Elmes herself was asked to select 43 children for the fourth convoy leaving from Rivesaltes.

Elmes would eventually get into arguments with the head of the Quaker organization in France, Howard Kershner. Specifically, they disagreed on the handling of Jewish children. Kershner felt that if the convoys of children were to be 100% Jewish, then Jewish organizations themselves should handle the administration.

In one letter Finn reproduces in her book, Elmes wrote of how she was “troubled to learn that Mr. Kershner feels that the Quakers should do no more in the matter of 100% Jewish emigration.”

In January 1941 Kershner held a meeting with Pétain, the head of the Vichy regime in which the Quaker stated the non-political nature of the work of the American Friends Service Committee in France. Later that year, Kershner met Pétain again.

By this stage the Vichy government had passed a second raft of anti-Jewish legislation. Kershner, however, did not bring up the subject with Pétain. Instead, he described in his personal journal all the delegates he personally met with from the Vichy government as “distinguished Frenchmen.”

Kershner seemed almost “starstruck” at the Vichy president, says Finn. “He was very keen to keep in with the authorities, to play by the rules, and was afraid to rock the boat in case the Quakers would be expelled.”

In mid-April 1942 Rivesaltes had more than 9,000 people living within its bleak enclosure, 40% of them Jews.

Conditions began to deteriorate. Food was scarce, weather conditions were harsh, and the children were infested with fleas.

And so four months before the first camp deportations to Auschwitz, Mary Elmes spent three days going from barrack to barrack, trying to persuade Jewish parents to allow their children to go on holidays to Quakers’ children colonies.

Initially, only 60 signed up for the scheme, though there were up to 300 places available. Finn says this was because spirits were still high in the camp, with many Jews believing they would eventually be released at this early stage.

By June of 1942, however, the mood had darkened considerably — not just for Jews in the camp itself, but across the whole of Europe. Target numbers for Jews to be deported from different countries across the continent were being set by the Nazis. In France the figure stood at 100,000.

The Quakers at Rivesaltes received the first definite information about Jewish deportations in the Unoccupied Zone in July 1942.

A time for desperate measures

There was an initial plan by the Vichy government to deport 10,000 Jews, who were taken from a number of camps in the south of France including Rivesaltes, Gurs, Vernet, Les Milles, Récébédou, and Noé. The first trains were scheduled to leave between August 6 and 12.

On August 7 the camp administration called a meeting of all the relief agencies informing them that children were to be deported along with their parents to Poland. It was at this stage that Elmes personally began to take groups of Jewish children in groups in her car and drive them away from Rivesaltes.

While Elmes was technically breaking protocol, Finn says she had the backing of most of her Quaker colleagues, who commended her bravery at the time. The new Quaker director in France, Lindsley Noble, for instance, wrote in his private notes on August 11, 1942, how Elmes had “spirited away nine children.”

Noble also noted how Elmes had rescued 34 children from Rivesaltes, as 400 Jews were being loaded onto cattle wagons towards Drancy.

“The camp authorities were working for the Vichy [government],” says Finn, “but some were very unhappy, and when they heard the deportations were going to start, they gathered all the aid agencies and said ‘They are grouping up all of the families and the children are going.’”

“When Elmes heard this in August of 1942, she began to take children in groups of five and six in her car at a time,” Finn says.

Of the 2,289 Jewish adults and 174 children deported in convoys from Rivesaltes to the east between August and October 1942, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact number of Jewish children Elmes and her colleagues rescued. However, the number is estimated to be 427.

“In those months, Mary personally is responsible for saving 80 children,” says Finn.

Finn’s book includes interviews with those personally transferred to the safety of the children’s home Elmes was running at La Villa Saint Christophe, where they escaped deportation.

Among these testimonies are interviews with brothers George and Jacques Koltein, as well as a rather moving interview with a woman named Charlotte Berger-Greneche.

The journalist tears up a little when she speaks of this latter interview.

Finn points to a letter she encountered in her research that came from Berger-Greneche’s mother. It consisted of her last words to her daughter, given to a Quaker worker out of the train as it was leaving Rivesaltes for Auschwitz.

“It simply said, ‘My most affectionate thoughts and a thousand kisses,’” Finn explains.

“I sent this letter to Charlotte, and she was blown away by this because she had nothing belonging to her mother before this,” says Finn.

Berger-Greneche was subsequently given a photograph of her mother by the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

“At 80 years of age that was the first time Charlotte saw a picture of her mother,” Finn says. “So little moments like that really show that Mary Elmes’s actions, and those of her fellow workers, still have resonance today.”

The unrecognized hero

In February 1943 Elmes was arrested by the German security police on suspicion of espionage. First she was taken to a military prison in Toulouse, and then later transferred to Fresnes prison. But with the help of both her Quaker employers and the Irish consulate in Vichy France, Elmes was eventually released in July that same year.

As recently as 2012 there was almost no recognition in Ireland of Elmes’s humanitarian bravery, with the notable exception of a couple of newspaper articles and the Holocaust Education Trust of Ireland, which honors Elmes at its annual Holocaust Memorial Day.

But in the last five years the courageous spirit of Elmes has been recognized, publicly, in France, Israel, and Ireland also.

“It Tolls For Thee,” a film narrated by Hollywood star Winona Ryder, has recently been made about Elmes bravery at Riversaltes.

Under the letter “M” in the Shoah Memorial in Paris at the Wall of the Righteous — dedicated to 3,900 brave souls who saved a number of Jews in France during the war — an entry now honors the name of Mary Elmes, who was born in Ballintemple, Cork, in 1908, and died in Perpignan, in the south of France in 2002, aged 93.

In 2016, Des Cahill, the mayor of Cork, invited Elmes’ granddaughter Marie Maude to a ceremony at the Council Chamber to honor her with a silver brooch of Elmes’s native city.

In Israel, meanwhile, Elmes was honored back in June 2014, when she became only the second Irish person ever to be named one of the Righteous Among the Nations (the first being Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty) — an honor conferred by the state of Israel at Yad Vashem to non-Jews who risked their lives to to save Jews during the Holocaust.

Elmes was nominated posthumously for the award by Ronald Friend, who, along with his brother Mario, survived deportation at Rivesaltes in 1942.

If it’s taken nearly 75 years for Elmes’ story to finally come to light, it may be because — as Finn points out — the former Quaker worker purposely shied away from the public limelight.

Under the letter “M” in the Shoah Memorial in Paris at the Wall of the Righteous — dedicated to 3,900 brave souls who saved a number of Jews in France during the war — an entry now honors the name of Mary Elmes, who was born in Ballintemple, Cork, in 1908, and died in Perpignan, in the south of France in 2002, aged 93.

In 2016, Des Cahill, the mayor of Cork, invited Elmes’ granddaughter Marie Maude to a ceremony at the Council Chamber to honor her with a silver brooch of Elmes’s native city.

In Israel, meanwhile, Elmes was honored back in June 2014, when she became only the second Irish person ever to be named one of the Righteous Among the Nations (the first being Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty) — an honor conferred by the state of Israel at Yad Vashem to non-Jews who risked their lives to to save Jews during the Holocaust.

Elmes was nominated posthumously for the award by Ronald Friend, who, along with his brother Mario, survived deportation at Rivesaltes in 1942.

If it’s taken nearly 75 years for Elmes’ story to finally come to light, it may be because — as Finn points out — the former Quaker worker purposely shied away from the public limelight.