Over the last several decades, it has become a tradition to eat cheesecake on Shavuot. While there is much speculation as to how the holiday commemorating the giving of the Torah became entwined with a decadent dairy dessert, the gamification of Sefirat HaOmer (counting the days between the holidays of Passover and Shavuot) has kept this obscure obsession alive, with Jews around the world tallying tenaciously day after day for seven straight weeks in the hopes of earning their holiday slice.

But this light-hearted diversion has distracted us from a serious problem in the Jewish community—one that has persisted for generations. While many of us rightly embrace Shavuot as an opportunity to renew our commitment to Torah study, there are many others who find the holiday daunting and inaccessible.

As this is assuredly not in the spirit of the day, I believe that we must reverse this trend by promoting a different view of the opportunity presented to us on Shavuot.

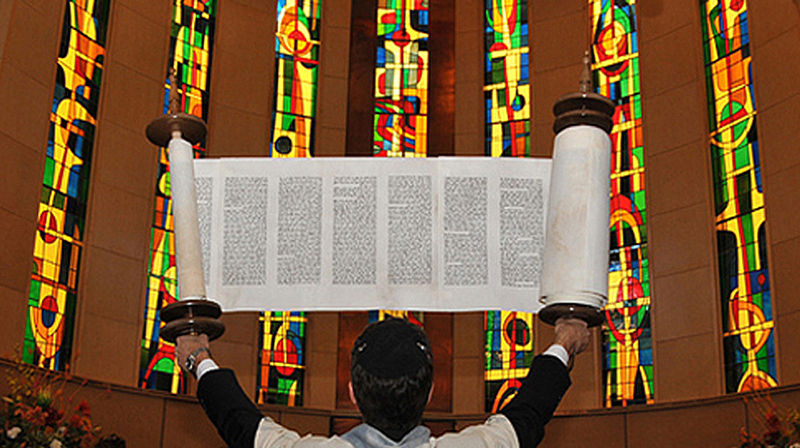

While Shavuot by its very nature is a communal holiday, the acceptance of the Torah is a very personal experience. At Mount Sinai, the entire Jewish nation—every man, woman and child, regardless of scholastic ability—accepted the Torah sight unseen (Na’aseh V’nishma—“We will do and we will listen”), entering into a special covenant and relationship with God. Thus, the Torah belongs to each of us equally, and the ongoing process of true acceptance is an individualistic pursuit. Each person has a different starting point, as well as the capacity to plot a unique route to Torah study that leverages his or her abilities.

The Shulchan Aruch (“Code of Jewish Law”) explains that the ideal way to carry out one’s daily acceptance of the Torah is by learning one chapter every morning and another in the evening. Referring to these twice-daily goals as a “single chapter” is somewhat misleading, as the Shulchan Aruch’s intention is for Torah learning to occupy the large majority of one’s day. While this prescribed method is generally unattainable in modern times, the underlying concept of beginning and ending one’s day with a Torah thought is still a very workable model.

Now more than ever, children and adults at every level of learning have access to a world of Jewish knowledge. Commentaries and translations abound, and the entirety of Jewish canon is at our fingertips. But instead of allowing ourselves to become overwhelmed by the enormity of Jewish knowledge to the point of forfeiture, we must seek out the specific text that speaks to us and helps us connect to God, Torah and Jewish life.

The Midrashic concept of Shivim panim l’Torah (literally, “Seventy faces to the Torah”) means that anyone, while grounded in tradition, can interpret our core texts in the ways that make sense to them. This open invitation encourages us to take the text and connect with it as we see it—to write our own notes, ask our own questions and take ownership. The Steinsaltz Center alone has published 310 titles that have made Jewish knowledge—from Bible to Talmud and everything in between—accessible to all, but this can only serve as the first steps in a much larger process. A true acceptance of the Torah comes from making it our own.

So while some may have seen Shavuot as a spiritual and intellectual gauntlet in years past, I believe that we all—from Torah beginners to scholars and everyone in between—need to take a step back and approach it from an entirely different point of view from this point forwards.

Rather than readying ourselves for an annual pedagogical marathon, we must treat the holiday like a buffet—a wondrous assortment of inviting options that can help us identify that one special thing that will ignite our personal journeys each and every day, and help us connect to Torah in our own inimitable ways. Focused on this task, we can sample from Jewish thought, philosophy and law, and expose ourselves to the vastness of Torah knowledge, without becoming overwhelmed or discouraged.

In this way, Shavuot becomes a golden opportunity to set our spiritual tables for the rest of the calendar year.

Now that I think about it, maybe Shavuot really is about working towards that one perfect slice after all.

Rabbi Meni Even-Israel is executive director of the Steinsaltz Center (www.steinsaltz-center.org), a pedagogical accelerator that develops tools and programming to encourage creative engagement with the texts and make the world of Jewish knowledge accessible to all.