The story of Sandy Koufax choosing not to pitch on Yom Kippur is one of the great narrative tales of modern American Jewish life. Depression-era slugger Hank Greenberg was also a role model for Jews seeking to step out of the stereotype of the helpless bullied victim in the years leading up to the Holocaust. But Koufax was a product of the postwar era in which Jewish pride was on the upswing.

During an amazing six-year run that lasted from 1961 to 1966, Koufax put together some of the greatest seasons of pitching in the history of the sport. But when Koufax was tapped to pitch for the Los Angeles Dodgers in the first game of the 1965 World Series, he chose not to play. Though not the least bit observant, Koufax knew what he had to do.

In the best-selling biography of the player by Jane Leavy—Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy—published in 2002, the author quoted an interview with Rabbi Hillel Silverman, who led several congregations in California and Connecticut, who said the Brooklyn-born pitcher who described himself as a “secular, non-practicing Jew” spoke once of his motives for sitting out.

“I’m Jewish. I’m a role model. I want them to understand they have to have pride.” He also felt that as someone who didn’t practice Judaism (he spent the afternoon in a hotel near the ballpark rather than in synagogue) but felt a strong connection with his people, it was an even greater sacrifice for him not to play, and therefore a fitting thing to do on a day on which Jews fast to atone for their sins.

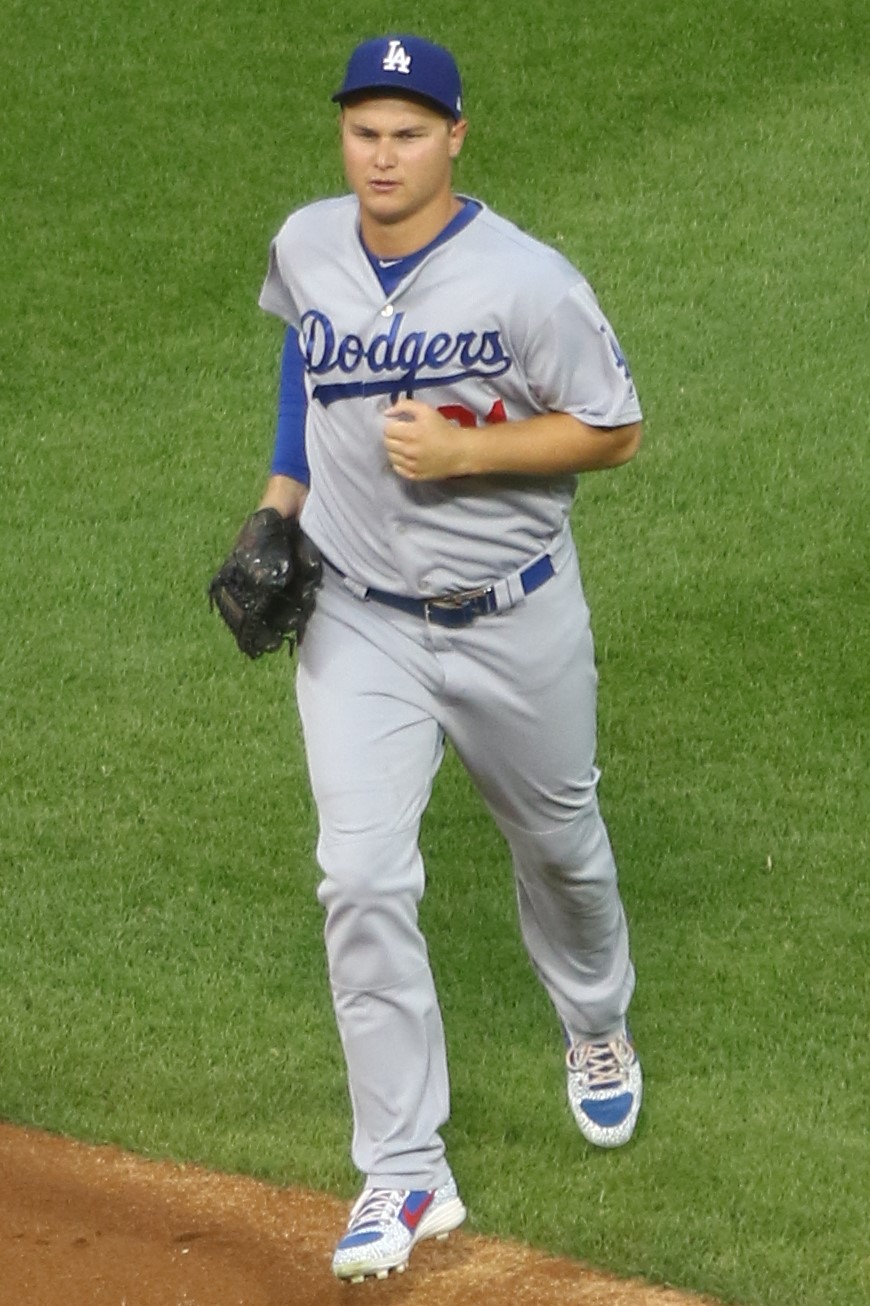

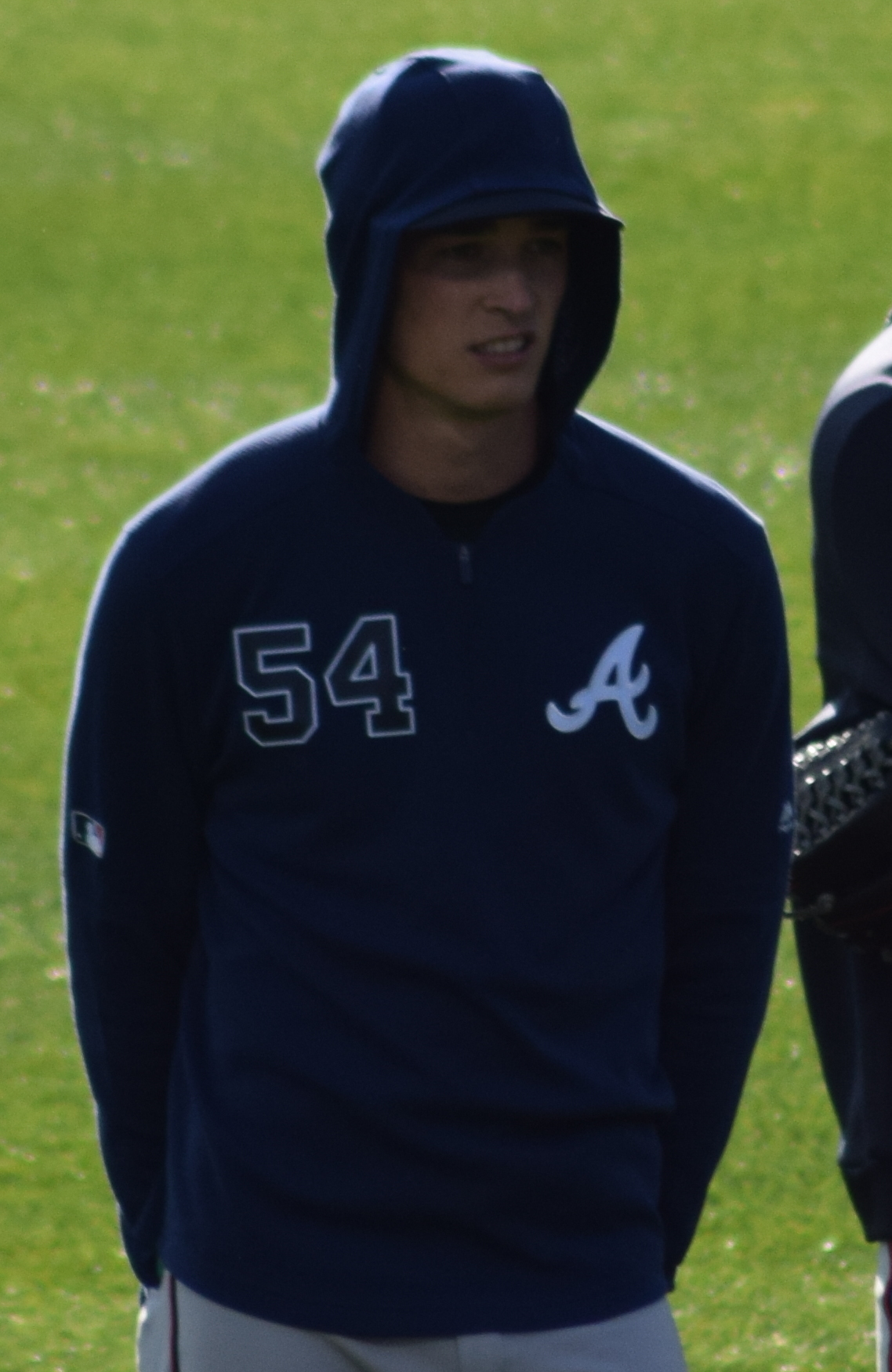

As has been widely reported, the observance of the Day of Atonement this year fell during a 24-hour period during which decisive divisional playoff games were held. The Houston Astros’ Alex Bregman, the Atlanta Braves’ Max Fried and the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Joc Pederson were presented with the same choice Koufax faced, but decided differently.

As Armin Rosen of Tablet magazine noted, the trio’s teams all lost. Rosen humorously asked whether this was a case of a “Koufax Curse” punishing the trio. Armin conceded that it’s hard to conceive of the Almighty choosing to intervene in the outcome of a few ball games to send a message to the world that the three men had offended heaven. But he wrote, almost certainly with tongue planted firmly in cheek, that the coincidence of them all being defeated on that day of all days left him wondering whether anyone really wanted to “bet that it’s not the hand of an angry God” at work.

Fried and Pederson, whose teams were eliminated from the playoffs (despite, or in Fried’s case, because of his unsuccessful performance on the field) on Yom Kippur aren’t likely to find Armin’s article terribly funny. Nor, despite the fact that the Astros won the next game and earned the right to play the New York Yankees for the American League championship, is Bregman likely to be terribly amused about being held up as the anti-Koufax.

Bregman, who has emerged in recent seasons as one of the game’s best players and is a strong candidate for the title of his league’s Most Valuable Player, once told Sports Illustrated magazine about how he spoke at his bar mitzvah of his ambition to be a professional athlete and his desire to be a “role model.”

But while Bergman appears to be an exemplary public figure, he won’t be remembered as Koufax’s successor. While that may be disappointing to those of us who still cherish the memory of how Koufax’s choice caused Jews to celebrate, no one should seek to shame him or the other two who played that day. In a free country, people have every right to determine their own priorities and live their lives as they like. In this case, that meant that all three considered their obligation to their teams, who are paying them huge sums that dwarf the salaries Koufax and Greenberg earned, to be of greater importance than religion or any thought of setting an example of Jewish pride for this generation.

More to the point, they are also a perfect metaphor for an era in which the notion of honoring a sense of Jewish peoplehood—the pull for Koufax and Greenberg, who missed a crucial game played on Rosh Hashanah in 1934—is increasingly irrelevant or anachronistic to the vast majority of American Jews.

This is an era with rates of assimilation and intermarriage increasing astronomically from where they were when Koufax sat out the World Series opener. Moreover, while Jews suffered discrimination in the 1930s and the Holocaust was a recent memory while Koufax played, the position of American Jews today is radically different. While anti-Semitism still exists, there is no virtually no sector of American society that is not open to Jews, even when they are observant as Connecticut Sen. Joseph Lieberman proved during his remarkable political career.

Stereotypes aside, in a world where Jews are not singled out in the United States the way they once were and where Israel is a regional military superpower, there’s nothing remarkable about Jewish men or women being athletes or examples of physical prowess. That’s why we don’t really need Bregman, Pederson or Fried to be our heroes.

We don’t have to look to a ballplayer—or any athlete—to prove that Jews are tough or accepted. Perhaps Koufax’s sacrifice is a throwback to a bygone era of Jews caring about demonstrating respect for their faith or their people’s heritage. But if so, then American Jewry is poorer for the fact that there are none to follow in his footsteps.