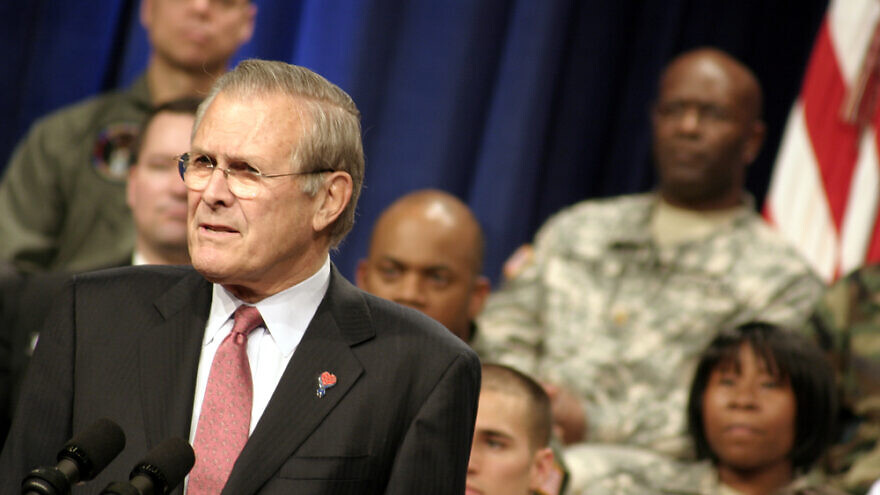

With ironic timing, the death of Donald Rumsfeld this week has occurred when American foreign policy is lurching in precisely the opposite direction to everything he stood for.

His passing has provoked a renewed chorus of bilious disdain from those for whom he was a lightning rod for the failures of the 2003 Iraq war in which, as America’s defense secretary, he played a key role.

But the real damage has been inflicted not by Rumsfeld but by his critics. For the war has been grossly mischaracterized, resulting in the world becoming a far more dangerous place.

No longer could America muddle along against its Islamist enemies. And over Saddam Hussein, until then America’s most active such enemy, U.S. policy had been adrift.

In his memoir Known and Unknown, Rumsfeld pointed out that between January 2000 and September 2002, Iraq attacked the U.S. military more than 2,000 times.

In the summer of 2001, Rumsfeld argued that America should develop a policy towards Iraq well ahead of any unforeseen events that might overtake the U.S., which could suddenly find Saddam posing an even greater threat.

Such an event happened on 9/11. Although intelligence didn’t suggest Saddam’s involvement in those attacks, Iraq was a principal state supporter of terrorism. The CIA said senior Iraqis had credible links with Al-Qaeda, which was seeking Iraqi contacts to help it acquire capabilities for weapons of mass destruction. And previous attempts to keep Saddam in check had all failed.

All these sound reasons for destroying his regime were ignored by Rumsfeld’s critics. The great cry went up instead that the West was taken to war on a lie that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction.

This false and malevolent characterization of the motive for the war, coupled with the grievous mishandling of the aftermath, produced the disastrous consequences of an anti-war movement that shaped a generation and the wider belief that the West should never again get involved in the Islamic world.

This reinforced an attitude already prevalent since the Vietnam war, a mindset which itself was to help contribute both to the crisis over Saddam Hussein and over the rise of Al-Qaeda and the Islamic jihad against the West.

For scarred by its defeat in Vietnam, America became demoralized and deeply reluctant to commit blood and treasure to foreign wars.

In Known and Unknown, Rumsfeld wrote that the U.S. retreat from Lebanon after the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Marine Corps and French army barracks in Beirut, as well as subsequent acts of terror, showed that America was still a prisoner of its Vietnam experience.

It was important, he wrote, that by contrast America should never cower in the face of terror or abandon its friends; the only way to deal with terrorists was to take the fight to them.

Over and over again, however, the enemies of the West have instead smelled American weakness. And this has galvanized them.

When the Marines fled after the 1983 bombing, wrote Rumsfeld, a young Saudi named Osama bin Laden observed that this demonstrated “the decline of American power and the weakness of the American soldier, who is ready to wage cold wars but unprepared to fight long wars.”

It was then that bin Laden said he first conceived his attack on the World Trade Center. In September 1984, after U.S. forces had withdrawn from Lebanon, the US embassy annex was nearly destroyed by a bomb, the third major attack on Americans in Lebanon in three years.

Saddam Hussein also believed that America wouldn’t have the stomach to fight him to the finish.

What Rumsfeld’s foes overlook is that Saddam had long been viewed as such a danger to America that a law mandating regime change in Iraq had been introduced by President Bill Clinton in 1998.

But after the debacle in Iraq following Saddam’s removal, subsequent presidents wanted America to retreat from active involvement in the region. This merely resulted in one perverse effect after another.

Thus, President Barack Obama laid down red lines against Syrian President Bashar Assad’s use of chemical weapons in Syria which Obama then proceeded to ignore, with unspeakable atrocities occurring in Syria as a result — and the U.S. being viewed as a paper tiger.

One reason why Obama wanted to bring Iran in from the cold through the 2015 nuclear deal was to enable the U.S. to get out of the Middle East. Absurdly, he thought he could bring this about through evening up the balance of power in the region between Shi’a Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia, thus achieving a geopolitical equilibrium. But all he achieved instead was the empowerment of Iran, the most lethal rogue state in the world.

During the U.S. election campaign, President Joe Biden affirmed his intention to “end the forever wars” to which the U.S. had been party.

But the result has been merely that America now finds itself gravely weakened when it is inevitably sucked into conflicts that are too dangerous to ignore, but where its demonstrable absence of resolve further emboldens the enemies of the west.

In Iraq and Syria, the Biden administration forlornly announced early this week that it had carried out further airstrikes on Iran-backed militia groups “to disrupt and deter” the increasingly sophisticated drone strikes on U.S. positions.

Regarding Iran, the Biden administration’s palpable eagerness to reinstitute the 2015 nuclear deal has merely provoked ever-increasing Iranian intransigence and repeated attacks on American interests. The U.S. response has been feeble to non-existent, thus provoking yet more Iranian aggression.

America’s unconditional renewal of funds and diplomatic recognition to the Palestinian Authority, in apparent indifference to its continued incitement against Israel and support for terrorism, has caused the Palestinians and their Iranian backers to conclude that they can continue to launch rockets and firebombs against Israel with zero risk that America will hold them to account.

In Afghanistan, where President Donald Trump demonstrated his own isolationist mindset by unwisely announcing a withdrawal of American troops, Biden announced he was accelerating this timetable.

As a result, the Taliban has been making rapid advances by unleashing violent attacks upon the Afghan army. Now the Biden administration is panicking.

Officials say that the U.S. could complete its troop withdrawal from Afghanistan within days. However, as many as 1,000 troops may still remain after the formal withdrawal to help protect the U.S. embassy in Kabul and the city’s airport.

And military officials are actively discussing using U.S. warplanes or armed drones to intervene in a potential crisis such as the fall of Kabul, the Afghan capital, or a siege that puts American and allied embassies and citizens there at risk.

Donald Rumsfeld understood that the biggest “known known” in the defense of America and its allies is the need to display unwavering resolve against the enemy. And if that means keeping troops on the ground for the long haul in Afghanistan to prevent the return of Al-Qaeda, so be it.

In his valedictory speech when he left the Pentagon, he said, “A conclusion by our enemies that the United States lacks the will or the resolve to carry out our missions that demand sacrifice and demand patience is every bit as dangerous as an imbalance of conventional military power. It may well be comforting to some to consider graceful exits from the agonies and, indeed, the ugliness of combat. But the enemy thinks differently.”

Indeed, it does. And the Biden administration is learning this — or failing to learn it — the hard way.