When my grandfather, a Holocaust survivor, passed away very suddenly in 2008, I went through his office in hope that he had documented his experience—that he had in some capacity written his story down, ensuring that it would be documented and preserved for generations to come. I had never had the nerve to encourage him to share his full experience and devastation in thinking that his story was gone forever. Of the 500,000 Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, only around 100,000 are still alive today, which leads us to the inevitable question: What will happen when there are no more living survivors?

My grandfather did not try to openly discuss the Holocaust. He would avoid the topic with us and would never explicitly tell stories of his experience. However, it was always there. We somehow all knew. There was never a time in my life that I did not know about the Holocaust. There was never a time that I did not know my grandfather was a Holocaust survivor. He would cry. He would share memories without realizing. His experiences came out in sudden bursts. He would express himself in his own way.

I have learned at least one very important thing since he passed: Just because he is no longer alive, it doesn’t mean his experiences have not, and cannot, shape, educate and inspire.

In my current role as director of education at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust, I do my best to ensure that ever-important history and stories like my grandfather’s can resonate with students from different backgrounds, experiences, families and communities. It was during my time at the University of Haifa, enrolled in the Weiss-Livnat International MA Program in Holocaust Studies, where I was not only able to affirm my desire to work in the Holocaust field, but further my commitment to preserving previously unrecorded survivor testimonies. Continuing dissection of the actions and subsequent consequences of the Holocaust is imperative to both maintain remembrance of the past and prompt future education.

One of the most important ways we can do that is through intergenerational dialogue—speaking and learning from those who have firsthand accounts. We should be focused on the survivors here with us today, bringing together students of all ages and cultures with survivors for meaningful experiences. We have an incredible opportunity to still share their stories—and we need to seize it. These 100,000 survivors are here, and our main focus must be on creating educational engagements with them.

I believe that there are three important factors to Holocaust education. The first is primary sources, the precious artifacts that miraculously weathered the Holocaust: documents, objects and, of course, photos.

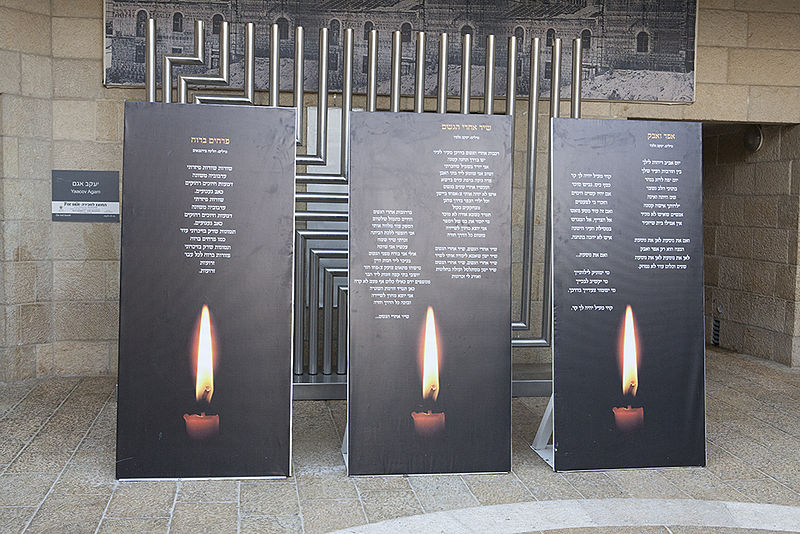

The second component of Holocaust education is the physical space of museums and memorials. They are built across the globe, either to mark cities of mass atrocity, memorialize vanished communities, or bear witness in cities where survivors and Jewish communities live on. These are spaces for visitors and locals to congregate, mourn and learn. They are community spaces that are tangible buildings offering reflective, meditative and educational opportunities, and their imprint on our societies and continued existence are vital for the future of Holocaust education.

The third factor, however, is without a doubt the most relevant and important: Holocaust survivor testimony, from the people who witnessed this atrocity and can speak to it directly. They survived the horrors and are brave enough to trust in the world again. This is the true human element. Through my work, I witness the intergenerational dialogue and interaction between students and Holocaust survivors every day. This is the most meaningful and important aspect for most of the students. This is where history is brought to life. The pain, fear and joys are all alive.

I may not be able to detail the exact experience of my grandfather. I definitely don’t have enough information to write a book on him, and I don’t have a testimony or interviews to use in an educational documentary. But I am a person who knew him. I remember him. I remember what he taught me. This I can share with other people. There is something personal in this form of engagement and learning. I truly believe that the generations born from survivors can and will steward this history.

We will always have precious artifacts, museums and memorials, but we must face the reality that we won’t always be lucky enough to rely on Holocaust survivors themselves to preserve their memory and continue their legacy. However, I believe that with testimonies, documentations and the decentness of Holocaust survivors standing to share the stories, there will be a strong future of Holocaust education. Silence usually follows traumatic events; survivors did not want to speak of their experiences. This has evolved, though. The grandchildren of Holocaust survivors are learning to speak freely of their inherited Holocaust trauma and of the legacy left by their grandparents. This third generation has become the new voice, rising up to ensure that the world never forgets.

Jordanna Gessler is director of education at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust and an alum of the University of Haifa’s Weiss-Livnat International MA Program in Holocaust Studies.