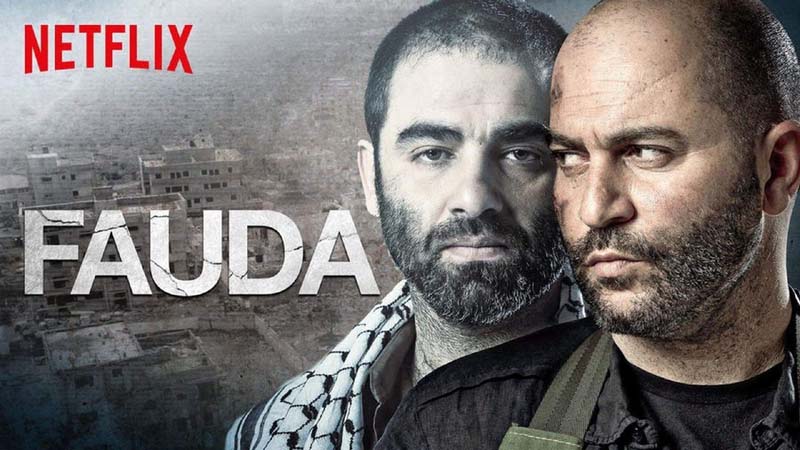

In the international hit Israeli TV series “Fauda,” the head of the Palestinian Authority security service is a fictional character named Abu Maher. Played by Qader Harini, an Arab actor from eastern Jerusalem, Abu Maher is reconciled to peace and coexistence, and therefore willing to cooperate with the Israelis to combat Islamist terror.

In an episode of the show’s second season (this is not a spoiler for the main plot line, so you can keep reading even if you haven’t watched the series), Abu Maher takes his son—a student who sympathizes with Hamas—to lunch on the Jaffa beach inside Israel. He tells the youngster to look at the skyscrapers of neighboring Tel Aviv. Those mighty buildings and the industry, creativity, power and wealth they represent, he says, show the permanence of Israel. The Jews are interested in life rather than death, and since they can’t be defeated, Abu Maher believes that the Palestinians must choose peace.

I thought of that episode when I read a recent controversial article in Haaretz by Ori Mark arguing that it wasn’t too late for two states.

Though its statistics were questionable, it made the case that is still possible to draw a border between a viable Palestinian state in the West Bank that would leave most Jewish settlements inside Israel. His map would leave about 46,000 Jews in isolated communities that would need to be evacuated in order to implement the scheme. To make it sound less daunting, Mark calculated that meant evicting only 9,800 families.

Put that way, the idea sounds vaguely doable, even if the memory of the traumatic evacuation of far fewer Jews from their homes in Gaza in 2005 is still fresh in the minds of Israelis.

The proposal set off a debate with some of Mark’s fellow leftists lamenting that the large numbers of settlers and the political strength of their supporters makes the notion of throwing that many Jews out of their homes unimaginable. Similarly, some on the right were just as dismissive of the proposal since they believe that the two-state solution is already a dead letter, and that the movement to establish Israeli sovereignty over the territories is headed towards inevitable victory.

But the problem with the arguments of Mark and his critics is that—like so much of the debate about potential borders that has raged in the last 25 years since the Oslo Accords—they both largely ignore the main obstacle to peace: the Palestinians.

The Haaretz piece was right about two things.

One is a non-starter: the idea that Israel can be forced back to the 1967 lines, and all of the settlements in Judea and Samaria, as well as Jewish neighborhoods in Jerusalem built over the so-called “green line,” demolished. Though many Arabs—and what remains of the once politically powerful Israeli left and their foreign sympathizers—may still think such a scenario is possible, the notion that hundreds of thousands of Jews and their communities can be uprooted is not realistic. The settlement blocs and post-1967 Jerusalem will stay in place in any conceivable plan for peace.

But Mark’s article was also correct when he noted that the government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has more or less frozen the number of settlements in place over the course of the last decade, rather than (as his critics constantly allege) vastly expanding them and thereby rendering two states impossible.

The border Mark draws with long and narrow corridors linking settlements to the rest of Israel, and a barely contiguous Palestinian state, seems crazy. So is the idea of sending the army into the 33 isolated communities that Mark envisions being left behind in a Palestinian state to drag approximately 46,000 people out of their homes. But if ordered to do it, I believe the Israel Defense Forces would accomplish the task, even if the cost in terms of civil peace and even potential casualties on both sides would not be cheap.

Yet that would only be possible if the Israeli government that gave that order had the support of the majority of the Israeli people. And the only way for that to happen would be if most Israelis were convinced that they were trading land for peace rather than for more terror, as they learned they had done at Oslo and with the 2005 withdrawal from Gaza.

That would require most Israelis to be convinced—as many were for a short while during the period of post-Oslo euphoria—that the Palestinians had given up their century-long war against the Jews.

Such a development doesn’t require a sensible map or a realistic plan for evicting a specified number of Jews from their homes.

It merely requires the emergence of a P.A. leader like the fictional Abu Maher, who could count on the support of most Palestinians and also be trusted by Israelis. Such a person would have to be willing not only to establish peace with the Jews, but also to fight and defeat the radicals inside Fatah, in addition to Hamas and other Islamist groups who are willing to sacrifice more generations of Palestinian children on the altar of their never-ending war.

But as long as such a figure is just a figment of the imagination of a team of Israeli TV writers, debates about how to draw a line between two states in the small territory shared by two different peoples remain so much hot air.