Israel’s outgoing interim prime minister, Yair Lapid, opened his Yesh Atid Party meeting on Monday by addressing the infamous “override clause.”

“It will crush the court; it will crush Israeli democracy,” he said, referring to one of the main issues dividing Benjamin Netanyahu’s coalition-in-formation and the rival “anybody but Bibi” camp that lost the Nov. 1 Knesset election.

Exiting Transportation Minister and Labor Party chair Merav Michaeli posted about her faction’s “first conference to save democracy and the justice system,” held to “unite the forces of good…to fight the dangerous override clause that is liable to critically harm the legal system and…the rights of all of us.”

The list of doomsayers about the proposed amendment—aimed at enabling the Knesset to “override” Supreme Court reversals of laws it enacts—goes on. Some detractors have been highlighting the slim majority of MKs (61 out of Israel’s 120-member parliament) that promoters suggest should be sufficient to dismiss judges’ unwanted interference.

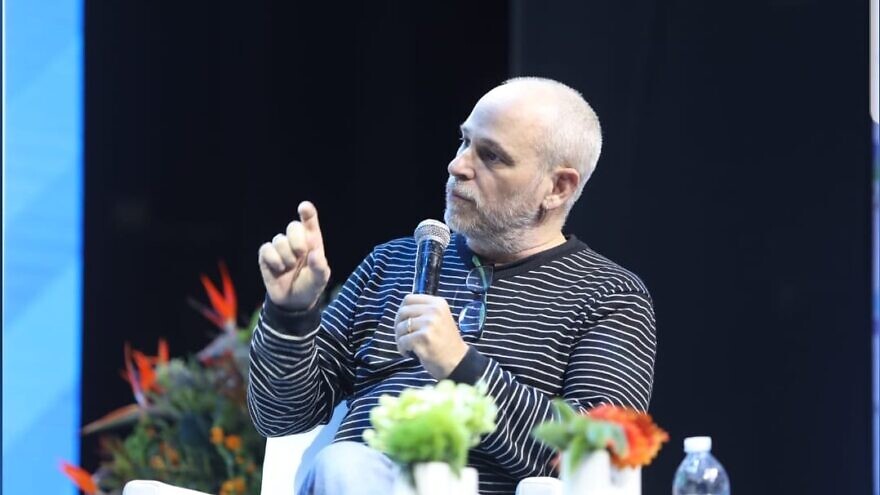

This isn’t to say that all supporters of the override clause are comfortable with every detail of its incarnation. Take best-selling author and neo-conservative pundit Gadi Taub, for example. In a letter to colleagues over the weekend, the senior lecturer at the Federmann School of Public Policy and Governance at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem responded to a petition against the clause launched by a fellow academic—Dr. Yael Shomer of Tel Aviv University—in tandem with a separate one signed by 130 jurists and counting.

Shomer’s formulation boiled down to what has become a convenient catchphrase—the “tyranny of the majority”—bandied about by all override opponents, among them those lacking even minimal familiarity with the subject.

Taub wrote in an email, “Since the text [of the petition] expresses a professional opinion, but touches on politics, it is inappropriate for it to paint a partial picture…or ignore fundamental parameters that we certainly wouldn’t allow ourselves to disregard in the classroom.

“The text is meant to have an influence beyond the realm of academia, and thus contains elements that it needs to clarify for non-professionals [who] put their faith in [our research]. It is our duty, thus, to provide a complete picture. It should be taken for granted, as well, that we mustn’t frivolously join in declarations, some of which border on actual irresponsibility,” he said.

Taub’s expansion on this, which included a thoughtful examination of the flaws of the petition, was countered by Hebrew University political scientist Gayil Talshir.

“The key question surrounding the override clause,” she replied, “is what majority [should be] required for the Knesset—not the government, which in any case is enormously powerful—to overrule a High Court of Justice ruling that an ordinary law is unconstitutional (i.e. violates civil or minority rights, or goes against Israel’s being Jewish and democratic).”

Taub’s 19-point answer warrants study by every member of the newly instated 25th Knesset. The following is my translation, for foreign consumption:

- There is no dispute that in Israel there is no structural separation between the legislative and executive branches. This is not unique to Israel; it characterizes the parliamentary system everywhere. Does this mean that separation of powers only prevails in a presidential system? Certainly not. It means that the separation of powers is not hermetic in the parliamentary system, and thus the nature of its checks and balances is also different. But the remedy cannot be the authorization of a court with no defined limit to its power to have the final decision-making authority in all matters, when its members are not appointed by elected officials, but rather, in practice, by their peers.

- No other Western democracy’s court has such powers and such control over the appointment of its judges.

- In fourth place in the Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index is New Zealand, where the court has no authority to annul laws.

- Britain, a prominent example of a parliamentary system, is similar to Israel in another sense; it, too, has no written constitution. But this doesn’t mean a court with unlimited power is needed there. On the contrary, in the U.K., as in New Zealand, the court has no power to overturn laws.

- A coalition system does not mean, as is often said, that the government is all-powerful. On the contrary, such a government is dependent for legislation on the coalition, even on parts of the coalition; at times, when it numbers only 61 [lawmakers], a single MK can thwart it. In a parliamentary system, there is justification for this subordination, as the Knesset represents the entire public. But the fragmentation of the [multi-party] Knesset pushed us, due to an extreme electoral system, into a hard-to-manage situation (as evidenced by the recent rounds of elections). The weakness of the Knesset, due to this fragmentation, poses a particularly serious problem to governance.

- The Israeli experience illustrates how this situation enabled the power of the court to grow, with individual parties having come along [over the years] and vetoing reforms…What makes the Israeli situation unique is the question of whether this is the result of the weakness of the government vis-à-vis the Knesset and/or that of the Knesset vis-à-vis the Supreme Court. We have often heard from lawyers that it was the weakness of the elected branches that created a vacuum into which the court entered.

- Talshir writes that in Israel the court has returned few laws to the Knesset for review…and invalidated [only some of] them. The English court returns laws to the parliament for review, along with a recommendation that is not binding on the MPs.

- We are repeatedly asked what will happen if the Knesset decides to cancel elections. But our Knesset is restrained to an extraordinary degree, and the body that appropriated the power to cancel elections is precisely the court. If it decides to do so, who will restrain it? After all, the Knesset could, at any moment, cancel the ‘Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty,’ even by a majority of two [lawmakers] against one, and thus cut the foundation out from under the authority that the court took for itself, under the influence of [former Supreme Court President] Aharon Barak, in a single day. But it doesn’t. The court, on the other hand…[has] stated that “in rare situations” and under “extreme circumstances,” it is possible to exercise judicial review over the Knesset members elected by the public to form a coalition. In short, the court has taken upon itself the power to cancel election results “in rare situations.”

- Our method of selecting judges, which reproduces the political DNA of the justices far beyond the reach of public will, is unreasonable, and even less so where such extreme activism is concerned.

- Talshir writes that the court returned “only” 22 laws for the Knesset’s consideration. First, it didn’t return them for review; it invalidated them. Secondly, [22 laws] is quite a lot. Thirdly, this is just the tip of the iceberg. In other cases, it neutered the laws without actually invalidating them….[I]n others, it gave interim injunctions that canceled government decisions or threatened to invalidate them. …In a host of other cases, the State Attorney’s Office [legal counsel to the executive branch] declared a law “not High Court adjudicable,” thus killing it before it was even born.

- We are told that the court protects the minority from the majority.…But most of the time, it uses unlimited power to decide on contentious issues that should be matters for the parliamentary give-and-take that leads to compromise.

- The claim that the court defends the rights of the individual is not convincing either.…Israel violates the individual rights of its citizens wholesale, taking away their freedom and property too easily and without due process, [through] confiscation and arrests, which the court shamefully does not restrain. It recently also allowed the use of torture in criminal proceedings. Here was a case in which the legislature protected human rights, and the police and state prosecutor, with the approval of the court, trampled on them.

- The court’s blithe use of the concept of human rights leads to utter absurdities. The Deposit Law…[to temporarily withhold a percentage of wages from asylum-seekers until they leave the country] was deemed a violation of human rights, while [taxpayer-funded] public broadcasting was touted as a civil “right.”

- The definition of democracy is, indeed, the “sovereignty of the citizens.” This should be stressed in the face of the misleading discourse adopted by jurists following [Justice] Barak, who reduced the expression of this sovereignty—elections—to the rank of “procedure.” Talshir goes at least one step in this direction when she writes that “anchoring the protection of civil and minority rights against majority rule (in addition to a constitution that guarantees the rule of law and elections that guarantee the rule of the majority that can be changed) is a condition for democracy.” But elections are not “extra.” They are essential to democracy even in the narrow, logical sense.…[They] are a necessary condition for the existence of democracy, because there is no democracy without them.

- Talshir is correct that liberal democracy is meaningless without the protection of human and minority rights, but this isn’t to say that the “essence” of democracy is human or minority rights, since it is a system of governance that must determine how to protect these rights. That is through the sovereignty of the citizenry, without which the other rights are meaningless. (We’ve already seen what enlightened tyranny looks like, from the 18th century onward.)

- Talshir writes that “elections that seemingly exclusively reflect the ‘will of the people’ do not make a country democratic—see Syria and Russia, etc.” This is a very puzzling claim. In those countries, there are no free elections, and they do not reflect the will of the people.

- The idea that the will of the people is a fascist monster, and thus needs to have an unchallengeable authority placed over it, is misleading and, in any case, undemocratic. If the people do not want democracy, there will be no democracy. No court will be able to impose democracy—or liberalism (i.e. human rights), without the sovereignty of the people—from above. Those who recommend the latter side with Plato’s view of “substantive democracy.”

- Concentration of power in the hands of the court does not constitute insurance against the danger of the trampling of human rights. In Germany, the Supreme Court sided with Hitler [through] the Enabling Act [that] abolished the parliament…In the Dred Scott ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court supported slavery, while the elections that brought Abraham Lincoln to power led to its abolition in a bloody war.

- I myself, am not happy with a 61-majority override clause, which I think will lead to a battle between branches of government. In its stead, relations between them should be anchored in basic laws, the most urgent of which would define the limits of the court’s power and changing the method of electing judges. On this basis, it would also be possible to discuss the court’s authority to invalidate laws, for example, with a special majority. I fear, however, that the outcry against the override clause is not aimed at protecting minority or individual rights, but rather at preserving the [current situation] that is unparalleled in the democratic world for a very simple reason: that it is distinctly anti-democratic.

Ruthie Blum is an Israel-based journalist and author of “To Hell in a Handbasket: Carter, Obama, and the ‘Arab Spring.’ ”