For anyone unaware of Europe’s anti-Semitism problem, CNN’s “Anti-Semitism in Europe Poll 2018,” released this week, would have made for grim reading on many levels.

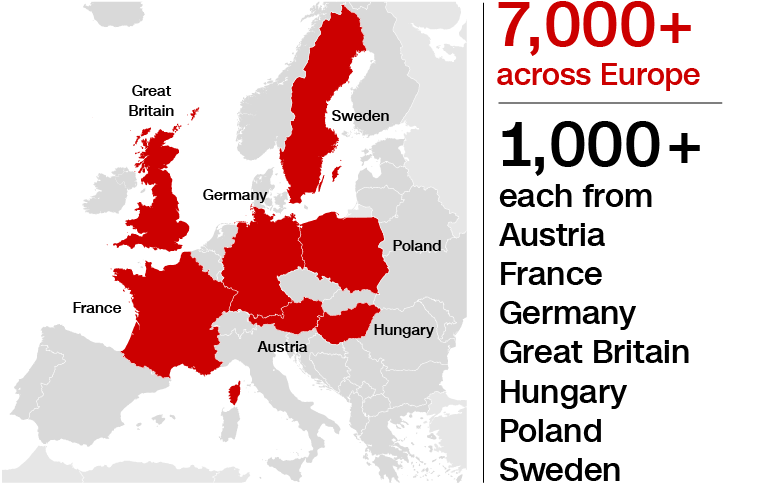

Polling 7,000 respondents in seven European countries, the survey revealed that one in 10 Europeans has an “unfavorable” attitude towards Jews, while nearly 30 percent believe that “Jewish people have too much influence in finance and business across the world, compared with other people.” When it comes to Jewish interests supposedly driving wars and conflict in the world, one in four Europeans believes that is indeed a decisive factor.

What are we to make of all this? Three conclusions strike me. First, anti-Semitism is rising in parallel with growing ignorance of history and growing intolerance towards other minorities in Europe. In the same poll, 16 percent of respondents reported “unfavorable” views of the LGBT+ community, 36 percent “unfavorable” views of Muslims and 39 percent “unfavorable” views of Roma (themselves the victims of a Nazi genocide that claimed the lives of up to 220,000 of this long-suffering people, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.)

Second, a greater number of respondents show some degree of sensitivity towards anti-Semitism, in that they see it as an offensive social problem. Forty-four percent of respondents agreed that “anti-Semitism is a growing problem in their country today,” while 40 percent believe that Jews face the risk of racist violence. When it comes to the intersection between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism—most often encountered by Europeans in the form of calls for the elimination of the State of Israel—54 percent of respondents concurred that Israel has the “right to exist as a Jewish state.”

Of course, one can read these numbers in reverse. A small majority of people don’t think that anti-Semitism is much of a problem, and nearly half of Europeans are somewhere between indifferent and completely hostile when it comes to the question of Jewish national self-determination. But that brings me to my third point; however you read these numbers, the data gathered in 2018 isn’t really new, even if headlines about anti-Semitism are far more prevalent now than compared with two years ago.

For example, take the approximately 30 percent of Europeans who think that Jews have too much influence over business and finance. Much the same number believed that in 2007. An Anti-Defamation League poll of that year found that 21 percent of German, 28 percent of French and a whopping 53 percent of Spanish respondents said that Jews “exercise too much power in the business world.” When the ADL conducted a similar poll in 2009 that included the same question, that figure had remained consistent in Germany, while rising a few points in both France and Spain. And more recent ADL polls in 2014 and 2015—in the wake of Islamist terrorism against Jewish targets in France and Belgium—showed that a little less than 25 percent of Europeans still harbored anti-Semitic attitudes and beliefs.

Even so, something has changed in the latter part of this decade, but what? I found something of a clue in a report on anti-Semitism commissioned by an E.U. agency way back in 2003 that contained this observation: “Opinion polls prove that in some European countries a large percentage of the population harbors anti-Semitic attitudes and views, but that these usually remain latent” (my emphasis).

I asked Abraham Foxman—the former national director of the ADL, who for more than two decades presided over that organization’s polling in Europe—whether one could still make that observation now. “Overt anti-Semitism has been more or less contained in the last 30-plus years,” Foxman told me during an email exchange. “We knew it was there, latent, but through many means, we created a firewall around it.”

That firewall, Foxman explained, was composed of the following elements. “First, the memory of Shoah,” he said. But also, “a civil contract of respect” in American public discourse; compelling anti-Semites in American public life, like the actor Mel Gibson, to pay the reputational price for their bigotry; educational initiatives explaining why anti-Semitism is, as Foxman puts it, “immoral, un-Christian and un-American”; and challenging lies and distortions about Jews (or code words for Jews, like “Zionists”) in social and mainstream media, often in coalition with other minority community partners.

“Most of these containment elements are dissipating,” Foxman told me. “[U.S. President Donald Trump broke taboos, coalitions are less effective—it’s more ‘me first’ these days—and media and journalism have been undermined.”

Because of that process, what was “latent” when the E.U. published its 2003 report has, in 2018, attained “greater license,” said Foxman. If that remains the case over the next few years—and there is little sign of a reversal coming—then the percentage of people who perceive anti-Semitism to be a social ill will diminish as the percentage of those who are “neutral” towards it, or even embracing of aspects of it, goes up.

Seven decades after the Holocaust and the creation of the State of Israel, the anti-Semitism that has been shaped since the turn of this century—nearly all of it recycled from previous manifestations of Jew-hatred—is at a new height of confidence, established on both left and right, and encountered less and less on the margins of both. Yet a slim majority of Europeans (and a great majority of Americans) still take a dim view of anti-Semitism and understand where it can lead. If this silent majority is encouraged to speak out boldly and loudly, then this latest battle can be won.