HAIFA, Israel — Tragedies often have a comic origin. This affair started out as being amusing and pleasurable, as well as uplifting, life-affirming and optimistic.

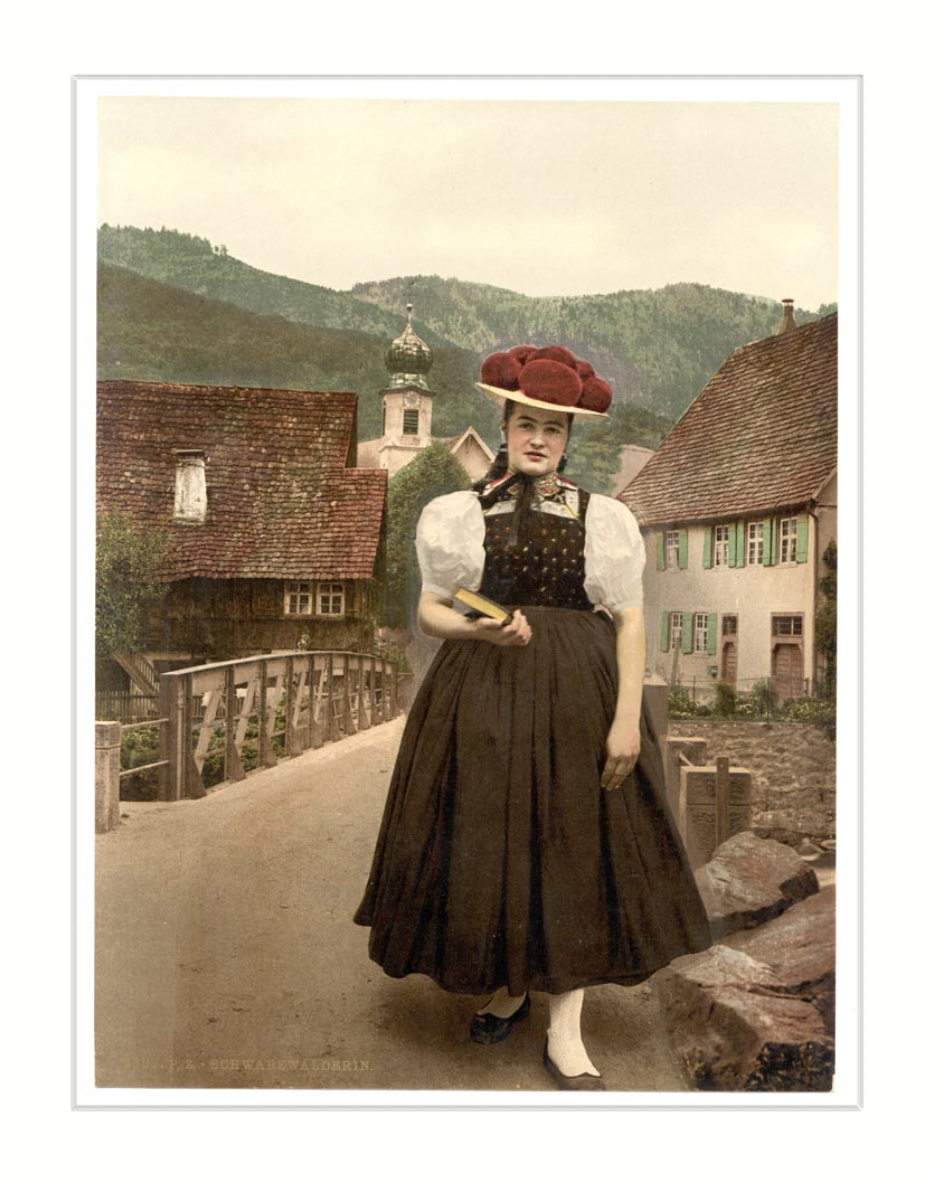

It is August 25, 1917 Berlin. The premier of the operetta, The Black Forest Girl (Schwarzwaldmädel) is performed at the Komische Oper theatre. It has been a huge success. The audience calls for the creator, one of the most famous operetta composers of the Empire, Leon Jessel. Applause explodes in the huge hall; there is a prolonged standing ovation. With 900 operetta performances in Berlin, and 6,000 in Germany and abroad, it will reign on the German stage for 16 years — until its prohibition.

Germany continues to march on its frontlines. The Parade of the Tin Soldiers by Leon Jessel in 1905 becomes one of the most popular musical marches of the time; one of the most famous German Christmas tunes. Military marches are soon to lose their popularity. They will remind everyone of the crushing and humiliating defeat of Germany, of offensive and distressing associations of The Great War. Defeated Germany is on its knees. Marches may not be popular, but The Black Forest Girl makes its triumphant march on the German scene. The nationalist and conservative ideology of Jessel, his brilliant, patriotic and lively music fit into the new German thinking. However, the composer himself, with his “shameful” Jewish origins, does not fit German society.

Leon Jessel was baptized in 1894 at the age of 23 because of his love for his first wife, Clara Louise Grunwald, and his dislike of the Jewish people and his Jewish origins. In 1896, Leon and Clara Louise were married in church. They settled in Berlin in 1911 and divorced in 1919. In 1921, this famous German composer married a young German nationalist, Anna Gerholdt who was 19 years younger than him.

The year is 1921, Berlin. Inflation threatens the Weimar Republic. A massive economic crisis is erupting in Germany. There is rampant unemployment. Everything is reduced, including the value of human life. Political assassinations are committed. Nationalism raises its ugly head. Anti-Semitic attacks break out. Jews are blamed for the war, the defeat of the country, and for the imposition of the humiliating and oppressive terms of the Versailles Treaty. Jews are distressed and anxious. Jessel is calm; the charges do not apply to him. He is a respected Christian. He is happy. The 50-year composer is married to a beautiful young wife, a girl of Aryan descent, the girl from the black forest, a real German. He rejoices in his marriage; he is in his prime.

Jessel is a prolific composer. He has written many orchestral works, piano pieces, songs, waltzes, mazurkas, marches, choral pieces, and other salon music. His operettas receive much recognition, especially The Black Forest Girl. His music becomes more lucrative at the same time that the currency is devalued; the monstrous inflation squeezes the country. Humiliated and robbed by the victorious allies, Germany starts marching. A few months after the marriage of the happy Jessel, right-wing extremists kill the German Foreign Minister, Walter Rathenau, a Jew. But Jessel is not concerned. He is no longer a Jew.

The murder of Rathenau passes him by, although it was carried out a few hundred meters from his home. He does not worry, he is not alarmed, does not look around, does not examine himself, nor associate himself with the incident. He does not see the monstrous pace of nationalist extremism. It is still too early; ten and a half years are to pass before the Nazi coup d’état. Parade of the Tin Soldiers continues to be played. It is heard in every home and is a feature of the Christmas holiday. The music-loving German people flock to the operetta The Black Forest Girl. Records of the jaunty and colorful works of the composer are sold out. Jessel prospers. His music captivates the soul of “his” people. Jessel’s operettas are nationalistic; very German. The Black Forest Girl is a favorite operetta of Hitler and Himmler.

Due to the success of his operettas, his conservative nationalist ideology and his second wife, Anna, joining the National Socialist Party in 1932 – even before the Nazis came to power – Jessel expects recognition by the Nazis. He hopes that Hitler will grant him the title of “honorable Aryan,” which he awarded to his favorite composer, Jessel’s kinsman and colleague, Imre Kalman. Kalman does not accept the title from Hitler and leaves for Paris, and later for the United States. Jessel remains intensely hopeful. But baptism and forty years of Christianity do not help. The Nazis reject him. Performance of his works is forbidden in 1933. In 1934 Jessel’s wife is excluded from the Nazi party.

In 1937, Jessel is dismissed from the State Institute of Music. Recording and dissemination of his works are prohibited. In 1939, the desperate Jessel writes to his librettist Stärk in Vienna: “I cannot work when hatred for Jews threatens the destruction of my people, and I do not know at what point a terrible fate will come knocking at my door.” After 45 years old, Jessel finally sees the Jews as his people.

For many years, the composer skillfully plays the role of a German musician, disguising himself in the mantle of the national composer. However, his art and his talent are not enough to buy him an entrance ticket to the German nation. Neither baptism, nor assimilation, nor imitation help the composer to receive equal rights with the German people for whom he has written his music. A great musician, Leon Jessel fails to become “theirs” to the people for whom he has worked, and his heart turns to stone. His love for the Germans turns to bitter disappointment with the nation and society. His many years of true service to German art are ignored. His despair and his disapproval are picked up.

On December 15, 1941, Jessel is arrested by the Gestapo for the dissemination of “horrible rumors” about the state. He is tortured in a basement at Alexanderplatz – the famous torture chamber. On January 4, 1942, as a result of torture, the composer dies in a Berlin hospital, a few days before his 71st birthday.

Eighteen months after the death of Jessel, distressing news came from faraway, safe Brazil of the suicide of the illustrious writer, internationalist, and pacifist, Stefan Zweig. Like Jessel, Zweig had disassociated himself from the Jewish problem, but after the Nazis came to power he became simply a Jew, utterly expendable in that German world which he could not bear to part from.

The good Christian Leon Jessel had written a highly popular Christmas march. While his toy soldiers continued their cheerful march, iron boots of the Nazis trampled Europe. The composer himself was arrested by the Gestapo in mid-December 1941. They tortured this upright, steadfast Christian throughout Christmas. He was beaten and humiliated by the very Germans who had been raised to love his Christmas music. The author of The Black Forest Girl was killed by boys and girls from the black forest of Nazism. They crushed this outstanding composer; he was finally regarded as no more than a Jew and, thus, unworthy of life.

Leon Jessel wrote a march about a fairytale Germany, magical, merry and benevolent but found himself in a cruel country, hostile to him. Leon Jessel, the tin soldier was thrown into the furnace, just as The Brave Tin Soldier from the fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. He, like countless Jews, was discarded in the furnaces of the Holocaust. He melted in the flame of unrequited love for Germany.

*

Alex Gordon is a native of Kiev, Ukraine, and graduate of the Kiev State University and Haifa Technion (Doctor of Science, 1984). Immigrated to Israel in 1979. Full Professor (Emeritus) of Physics in the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of Haifa and at Oranim, the Academic College of Education. Author of 9 books and about 600 articles in paper and online, was published in 79 journals in 14 countries in Russian, Hebrew, English, French, and German.