In the beginning

The arrival of the Jews in Spain is the subject of many legends, spread by Jewish and Christian chroniclers, especially in the sixteenth century. For some, they arrived at the time of King Solomon in the wake of Phoenician travelers; for others, the event was one of the consequences of the exile of the population of the kingdom of Judea, ordered by Nebuchadnezzar (1125–1104 BC). [1] Historians tell us that the first Jews arrived in a more or less organized manner after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE.[2]

They first settled on the Mediterranean coast and then gradually spread throughout the Iberian Peninsula. The oldest evidence of Jewish presence in Spain is a trilingual inscription in Hebrew, Latin and Greek on a child’s sarcophagus found in Tarragona and dating from the Roman period (now on display at the Sefardí Museum in Toledo). In addition, the mosaic of Elche (first century) was undoubtedly the floor of a synagogue, which is evidenced by the Greek inscriptions, as well as the geometric designs that compose it. Finally, texts reveal a Jewish presence in Spain at the same time: The War of the Jews by Flavius Josephus (VII, 3, 3), The Mishna (Baba Bathra, III, 2).

The Iberian Peninsula was, for fifteen centuries, the second land of the Jews. From Toledo, the Sephardic Jerusalem, to Granada, they lived in a state of flux between Christians and Muslims until their expulsion in 1492.

The anti-Jewish legislation of the Visigoth kingdom was severe, but these laws were hardly implemented in practice. On many occasions, new laws are found regretting that the previous ones were not applied by the Christians. The conversion of Jews was often a means of escaping these laws, but it was sometimes sincere, as shown by the example of the bishop and historian Julian of Toledo (642–690): [3] his family being considered perfectly converted, the Church appointed him primate of the whole kingdom.

Until the eighth century, little is known about Spanish Jewish communities. Under the Romans, Jews had the same status as in the rest of the Empire. During the reign of the Visigoth kings, who were Aryan, Jews were tolerated and made a living from agriculture. From 586 onwards, the date of the conversion to Christianity by King Recarede I (or Recared; Latin: Reccaredus; Spanish: Recaredo; c. 559 – December 601 AD; reigned 586–601), they were persecuted and forced to convert for almost a century (which led to the term “Marrano” [4] being used before the term was coined). King Egica (610 -701) even considered enslaving them.

Land of multiple colonizations, Spain, which belonged to the Visigoth empire, became, at the beginning of the eighth century, Al-Andalus, by yielding to the push of the conquering Islam. The majority of the population of the South converted, Cordoba and its grandiose mosque will be the beacon of Islam in the West, which tolerates Jews and Christians. Better still, in the tenth century, during the period of the Caliphate of Cordoba (929-1031), [5] Jews and Arabs experienced the same apogee: the political, economic and cultural strengthening of the Muslim power of Cordoba also corresponded to a period of splendor of the Jewish communities and culture of Al-Andalus.

When the Arabs arrived in 711, the Jews put themselves at their service. The Arabs were few in number and sought loyal allies. The two communities found it in their interest to get along, especially since many Jews from the Maghreb came to reinforce the presence of the Moors and the Jews of Sefarad. Moreover, some Arab geographers do not hesitate to declare that Granada, Tarragona and Lucena are “Jewish cities”, to mark the importance of this minority. The development of urban life required merchants and administrators, functions that the Arabs and Berbers were reluctant to perform.[6]

Arabic, language of tolerance and knowledge

Most of the Hispanics who remained Christian gradually became Arabicized: learning the language (Arabic became the majority language in the 12th century, supplanting the “Andalusian Roman”) and adopting the Muslim way of life (name, clothing, food, etc.): these are the Mozarabs. [7] The bishops encouraged the translation into Arabic of the psalms, then of the Bible and of the texts of canon law (even if Latin remained the liturgical language) and even of secular texts; Arabized Christians were used by the caliphate for diplomatic missions with regard to the Christian West: reception/translation of ambassadors in Cordoba, a bishop sent to Otto I in 955. The same is true for the Jews: Hidaï ibn Shaprout (915-975) managed the Caliphate’s diplomatic relations with the West and Samuel ibn Nagreda (993-1056) was vizier to the king of Granada (Taifa period) and even became warlord against Seville in 1038 and 1056.

From a cultural point of view, knowing Arabic gave access to ancient knowledge through Muslim scholars and the immense library of Cordoba, which contained 400,000 books. The writings of Muslim scholars (Indian numbering system, etc.), the texts of Aristotle and Plato, were thus transmitted to the West from Cordoba and, in the 12th century, from Toledo and its translations by the Mozarabs. It was in this atmosphere that Sephardic Jewish culture flourished, open to secular knowledge (philosophy, science, poetry), illustrated by Solomon ibn Gabirol (1022-1058-70), author of a neo-Platonic treatise. Seville, Cordoba, Granada (Toledo, Zaragoza) were home to the most flourishing Jewish communities. [8]

In fact, all this concerns only a very small minority, without any influence on a culture centered on the East, a trait that is also found in the field of the arts. More generally, Christians and Jews under Muslim rule (as well as Jews and later Muslims under Christian rule) had a status of “protected” dhimmi (in Arabic) with a pejorative nuance (legal inferiority). Each of the two dominant cultures (Islam, Christianity) are tolerant only insofar as it is impossible for them to make the others disappear (exile, real conversion), given the numerical importance of minority groups. This obligatory tolerance is more the work of the elites (economic, financial, diplomatic interests) than of the anti-Semitic, anti-Muslim (anti-Christian) people, depending on the case, because of religious and economic rivalries.

The al-Andalus period demonstrates this perfectly, as does the fate of one of the greatest thinkers in the history of Islam: Averroes (1126-1198).[9] Born into a family of jurists in Cordoba, he was first a cadi and then a doctor, before becoming the learned commentator on the works of Aristotle, which he made known in all its breadth to Westerners. Having lived at the crossroads of the two periods, he ended his life disgraced by the Almohads (1121- 1269).

Much of the transfer of knowledge from the Muslim world to the Latin world took place through the translation of Arabic from the medieval period onwards, notably through the School of Toledo and the Jewish translators of Arabic. Archaeological and historical research on al-Andalus has shown the importance of the Arab cultural heritage in the development of European civilization.

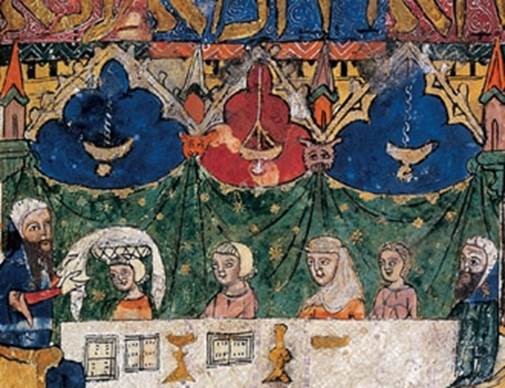

Andalusia during the Golden Age was a period of special growth for poetry, since it seemed to be rooted in the highly mundane concerns of man, in this case the Jewish man. Love poetry has also taken a prominent place. Perfectly bilingual (Arabic, Hebrew) and assimilated into their Arab-Islamic environment, the Jewish poets of the period – by their impetus and by the brand-new form of their poetic creation – raise the following question: at what level does Hebraic love poetry in the Andalusian Golden Age find its roots in Andalusian life itself and at what level do these roots go back beyond this period to the biblical Hebraic text? A comparative study between Hebraic love poetry and Arabic love poetry must proceed first to analyze the factors of the revival of Hebraic poetry, in general, in the first instance, and the factors of the revival of Hebraic love poetry and its origins in Arabic and Jewish cultures, in particular, in the second instance.[10]

On the nature of Arabic language in al-Andalus: [11]

“For the Jews in the Middle East and Spain, Arabic was the key to an entirely new way of thinking. There, too, Jews abandoned Aramaic for the new language, but Arabic functioned both as the language of high culture and the common tongue of both Jews and Arabs in everyday exchange. It was at the same time linguistically akin to Aramaic and Hebrew, with morphological forms and cognates that facilitated transcribing Arabic into Hebrew letters and reading it—the form of Arabic we call Judeo-Arabic. Assimilating Arabic was even less of a “leap” for the indigenous Aramaic-speaking Jews of the Middle East than it was for Jewish immigrants to Europe making the transition from Aramaic to European vernaculars. Furthermore, Arabic, the language of the Islamic faith, like the faith itself, was less repugnant and less threatening to the Jews than the language and doctrine of the Christian Church. “

The Jewish communities of al-Andalus

It is estimated that the first Jews arrived in Spain around 70 CE, after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Along with Toledo and Segovia, the Jewish community of Seville was one of the largest in Spain. More or less tolerated under the Romans and the Visigoths – who set up the Toledo Councils – the Jews welcomed the Arab conquerors at the beginning of the 8th century.

During the three centuries that followed, and until the fall of the Taifa kingdoms in 1086, the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula reached such a high economic and social position, and Sephardic culture such a level, that this period is unanimously considered to be the Golden Age of Judaism in Spain.[12]

The Jewish communities of al-Andalus – the territory of the Iberian Peninsula under Muslim rule – were particularly distinguished between the reign of the Umayyad caliph of Cordoba, Abd ar-Rahman III (912-961), and the Almohad takeover of power after 1140. No other medieval Jewish community had so many high-ranking personalities in the political and economic spheres; no other produced a literary culture of such scope, revealing an intellectual life shared with the Muslims. This flowering is all the more unexpected since the Jews of Hispania had lived in great social and legal uncertainty during the Visigoth period, when they had been persecuted and subjected to decrees of compulsory conversion.

A part of the Jewish population of al-Andalus, undoubtedly from the migratory waves of the Islamic conquests, embraced from the beginning the culture and language of the invaders. The unification of the territories and the adoption of the Arabic language thus constituted a fundamental change, as it facilitated, among other things, the establishment of fluid relations between the Jewish communities. In this process of Arabization, the peculiarity of Jewish literary culture is the extraordinary cultural vitality of the elites combined with their material prosperity, their participation in public affairs and in the administration of the courts of al-Andalus, their responsibilities within their communities, and their importance in Jewish history, which is a paradox, given the small number of their representatives.

Two scholars, one Jewish, the other Arab, contemporaries and both born in Cordoba, marked their time: Averroes, the Arab, born in 1126, a philosopher whose attraction was extraordinary on the minds, who saw his doctrine taught as far away as Paris; and Maimonides, the Jew, theologian, philosopher and physician, born in 1135 to a family of Talmudists.

I don’t think it is very fortunate to cite Averroes and Maimonides as two examples of freedom of thought and confraternity of communities in al-Andalus. Averroes was a Neoplatonist who was persecuted as a free thinker by the Almohads. As for the Jew Maimonides, he was forced to become Muslim. Exiled to Morocco with his family, he then went to Egypt where he returned to Judaism. Discovered and denounced by a resident of al-Andalus, he was accused of apostasy and was only able to save his life through the intervention of Cadi Ayyad (1083–1149). Maimonides sets out his position and mindset towards Christians and Muslims in his Epistle to Yemen. [13]

But the disappearance of a central Muslim power in Cordoba stirred up the covetousness of new Maghrebi conquerors, notably the Almohads: they pursued a very harsh policy towards Christians and Jews. Maimonides, fleeing their persecutions, emigrated to North Africa, preceding the great exodus that the Christians, in their turn, would impose on the Jews three centuries later. With the progress and then the victory of the Reconquista, that seven-century march from the mountains of the North which patiently won over the whole territory and made Spain a Catholic land once and for all, the Jews paid for their brief Spanish golden age. They were a bridge between Muslim and Christian society, developing an original culture. This cultural advance explains the part taken by the Jews in activities such as medicine and trade, especially that of money. Yesterday they were bankers to the caliphs and Muslim kings, and today they are financiers and tax collectors to Catholic kings. Their ostentatious power makes them unpopular, which extends to the whole Jewish community.

The culture of Sephardic Judaism[14] originated during the early Middle Ages in the shadow of the Muslim courts of Spain. From 711 to the middle of the twelfth century, flourishing Jewish communities had developed throughout Muslim Spain (al-Andalus), creating a vibrant culture in centers of Muslim power such as Granada, Cordoba, Lucena, Merida, Zaragoza and Seville.

The Jewish Golden Age

At the beginning of the Muslim conquest, the Jews avoided political office. Their Arabization allowed them to integrate into Muslim society and to change this situation thanks to the most talented among them. They were Jewish doctors, merchants or farmers. Two centuries later, in the 10th century, they were advisors to Muslim princes and some of them became even warlords i.e. Samuel Ibn Nagrela (993-1055).

The revival of medieval Jewish poetry in Arabic came from a singular man: Samuel ibn Nagrela, who is one of the greatest Richonim. He wrote an encyclopedia of Hebrew grammar in 12 volumes, and was the Nagid of Granada (representative of the community). But he was also the vizier, that is to say the prime minister and the chief of the armies of al-Andalus. He rode horses, commanded Muslims and fought wars, which was forbidden to a dhimmi and wrote poetry on the battlefield, translated Jewish poetry from Hebrew, and built the Alhambra of Granada. And his son Yoseph succeeds him. Unfortunately, he was not as clever as his father and was accused of wanting to assassinate the Sultan. He was crucified in 1066. 1500 families and 4000 Jews were exterminated that day (Granada massacre). [15]

“On Sunday December 30th, 1066 a Muslim group outraged with the Jewish people decided to incite a riot in Granada. As they stormed the royal palace, they were targeting one man. His name was Joseph Ibn Naghrela. Son of the famous Shmuel Hanged, he was the Jewish vizier to the Berber King Badis al-Muzaffar of Granada. This enraged the Muslims of Granada because a Jew was able to create a vertical alliance within what was thought of as a primarily Muslim dominated area. Because of a political poem written by Abu Ishaq. Within this poem, Ishaq called for the killing of the Jews. This in turn organized a group of Muslims that did indeed start this mass murder. Because of this, it is recorded that nearly four thousand people fell to their deaths that day. “ [16]

Ibn Ihsaq’s poem played a very important role in the Granada massacre of 1066. It expressed his frustrations with the Jewish people, thus creating a kind of “poetic propaganda”. At that time, poetry was used for more than the current definition of poetry. Some poems dealt with life, death, and other themes that seem to be recurring in modern poetry, but poetry was also used as a political statement and thus a political weapon. Poetry was known as “the supreme ornament of Arab culture“. This shows the importance of poetry for Arab culture, and especially for Muslims.

According to the historian Bernard Lewis, the massacre is

“usually ascribed to a reaction among the Muslim population against a powerful and ostentatious Jewish vizier.” [17]

He further writes:

“Particularly instructive in this respect is an ancient anti-Jewish poem of Abu Ishaq, written in Granada in 1066. This poem, which is said to be instrumental in provoking the anti-Jewish outbreak of that year, contains these specific lines:

[Do not consider it a breach of faith to kill them, the breach of faith would be to let them carry on.

They have violated our covenant with them, so how can you be held guilty against the violators?

How can they have any pact when we are obscure and they are prominent?

Now we are humble, beside them, as if we were wrong and they were right!] “ [18]

Lewis continues:

“Diatribes such as Abu Ishaq’s and massacres such as that in Granada in 1066 are of rare occurrence in Islamic history. “

With these clearly being calls to arms against the vizier and the Jews of Granada, it has been directly linked to the riot that ensued and killed so many innocent Jewish people on December 30th, 1066. [19]

The medieval Jewish golden age actually lasted only a very short period in Muslim Spain, from 1002 to 1086. As Gérard Nahon writes:

“this period is only a short interlude in a bitter history marked by wars, displacements and extortion, an interlude essentially internal to the Jewish community which gave the best of its intellectual and spiritual expression. This was achieved not because of the idyllic conditions of existence in the shadow of the Crescent, but in spite of the inferior and precarious situation that remained its lot. “

The high figures of this period are: Jonah ibn Janah, whose real name was IЬn al-Walid Marwân Ibn Janah (Córdoba 985 – 990); the Hebrew poet and grammarian Moses ben Jacob ibn Ezra also known as Abu Harun (Granada 1055 – 1138); Salomon ben Judah ibn Gabirol (1020-1057) in Arabic Abou Ayyub Sulayman ibn Yafryâ, in Latin Avicebron or Avencébrol, De Bahyé ben Joseph Ibn Paquda, (1050 – 1120), navigating between the Christian and Arab kingdoms. The Jews became grammarians, lexicographers, poets and philosophers in a renaissance of Hebrew and poetry in the Arabic language that has not been equaled since.

The middle of the 13th century sounded the death knell of peace for the Jews. In 1263, Nahmanides (1194-1270) fell into the trap of the Barcelona dispute with Father Pablo Cristiano, a Jewish convert to Christianity. The following year he went into exile in the Holy Land.

From the establishment of the Caliphate of Cordoba in 929, a golden age of Judaism in the land of Islam began. Abd Rahman III (912-971) took Hasdai ibn Shaprut (910-970), a Jew from Jaen, as his physician and entrusted him with many diplomatic missions in addition to his own health: contact with the abbot of Gorze, negotiations with the emerging kingdoms of León and Navarra. Hasdai ibn Shaprut was a very wealthy courtier whose life was sung by the poets Menahem ben Saruc (920-970) and Dounas ben Labrat (920-990). He had many scientific works translated from Greek into Arabic, and contributed greatly to the cultural development of his community. In contact with Arabic poetry, the Jews composed beautiful poems and invested themselves in grammatical studies; all this intellectual effervescence favored the blossoming of a rich Hebrew culture.

In the eleventh century, Granada was the capital of the Arab world in Spain. Samuel haNaguid, or the Naguid (993-1056),[20] was the key figure of this period. This merchant from Malaga quickly became the leader of Granada’s politics; he did not hesitate to lead the Arab troops in their fight against Seville or Almeria. He was also a poet and a very learned rabbi, and he favored the arts and, in particular, poetry, as did his son Yoseph, who succeeded him at his death.

Sephardic Judaism

The specificity of Sephardic Judaism stems in part from the exceptional diversity of the Iberian Peninsula in the medieval period, housing Muslims, Christians and Jews, and the special place they occupied both politically and culturally.

While little is known about the lives of the first generations of Jews following the Muslim conquests of 711, it is likely that the Arab invasion triggered a wave of Jewish immigration to Spain after a century of persecution under the Christian Visigoth kings. The wealth and opportunities offered by Spain were a magnet for many peoples of the Mediterranean region. With the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba under Abd ar-Rahman III (889/91 – 961) and al-Hakam II (915 – 976), an independent Muslim power center emerged, rivaling Baghdad in wealth and culture. The Jews of Spain loosened their ties with the Jewish communities of Iraq and independently developed an independent culture and local Talmudic authority. Under the influence of Arab traditions of refinement, they began to experiment with new cultural forms in the Hebrew language. Poetry, linguistics, science, philosophy and mathematics complemented their age-old interest in the Bible and the study of the Talmud.

In all conquered regions, the Arabs tended to create new urban centers of civilization where their intellectual affinities prevailed. The interest in the Arabic language, Arabic poetry and Arabic grammar was at the heart of Muslim civilization. A taste for the classics and an openness to ancient history and philosophy, science and mathematics were secondary but increasingly important. Islam with its compilations and legal codes permeated everything. But it was not until the Almoravids and Almohads, in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, that it exerted its full influence in Spain. The adoption of Arabic by the Jews introduced not only a new vocabulary, but also an entirely new way of thinking, allowing the Jews of Muslim countries to participate in and integrate into the dominant culture in a way that they had never been able to do in Christian Europe.

In the tenth century, the Umayyads of Cordoba had succeeded in transferring to Spain much of the imperial and artistic tradition of Baghdad. Jewish merchants had not only brought the luxury goods of the East to Spain. They also brought with them the intellectual achievements of the Talmudic academies of Baghdad. Thus a Babylonian prayer ritual had arrived in Spain in the ninth century and the Spanish Jewish community was able to participate in a common Mediterranean culture with its roots in the East.

The very active cultural life of Cordoba was a source of inspiration and imitation in the fields of synagogue architecture, poetry and medicine. Jewish scholars from abroad were invited to Cordoba to establish an independent academy in the city, and linguists and grammarians were employed as secretaries to princes while exploring new poetic forms. Hasdai Ibn Shaprut was not the first medieval Jew to play an important role in public life, using his political position to develop Jewish culture. Several Jewish figures also emerged from obscurity at the same time in Iraq. But he was the first to play such an essential role in launching a cultural movement known to this day in Jewish history.

Despite its fame, Cordoba was never the only center of Andalusian culture and Jewish creativity. Other equally fertile centers of Islamic civilization, deliberately imitating the capital, also sprang up in Seville, Granada, Malaga, and Lucena after the dismemberment of the caliphate.

Like their Muslim contemporaries, Jews studied a variety of extraordinary subjects, including astronomy, astrology, geometry, optics, rhetoric, calligraphy, philology, metrics, medicine, philosophy and Arabic. It was also essential to complete rigorous studies of the Hebrew tradition, including the Bible and Midrash, the study of the Hebrew language and the study of the Talmud. The special emphasis on the arts and foreign languages reflected the prevailing Arab cultural tradition, in which a man was judged on his literary abilities as well as his social qualities.

Muslims had a special attachment to the Arabic language and held poetry in high regard. Under their influence, Jewish culture evolved in new directions. In Andalusia, not only was perfect mastery of Arabic a prerequisite for entry into the civil service, but refinement of diction and expression, even to the point of affectation, especially in courtier circles, was the royal road to rapid promotion. Muslim society showed a passion for eloquence, precious style and decorative details, reveling in esoteric turns of phrase and expressions dating from the pre-Islamic period of the Arabic language. Jews, having long emphasized the verbal rather than the visual, felt a special affinity with Muslims regarding their predilection for language over image. They realized that a perfect command of Arabic was a prerequisite for entry into public office and political advancement. Most of the classical, philosophical, and scientific works composed by Sephardic scholars in Spain, including some of the most deeply rooted texts in Judaism, were written in Arabic.

Spanish Jews remained committed to science and mathematics in Spain, frequently serving as agents for the dissemination of Arabic science through their active role in the translation of scientific works from Arabic into Hebrew. They continued to explore the practical and theoretical sciences until the eve of the expulsion, both in Christian and Muslim Spain.

From Umayyad Cordoba onward, Jewish scientists built astrolabes to calculate latitudes, working especially to improve astronomical tables and navigational instruments during the voyages of exploration to Spain and Portugal. The poet and exegete Abraham Ibn Ezra (1089-1164) [21] wrote three books on arithmetic and number theory, accurately describing the reception of Indian numbers in the Islamic East. The Hibur ha-Mechihah ve ha-Tichboret by the Barcelonan Abraham Bar Hiya (1070-1136), a 12th century treatise on practical geometry, was the first Hebrew scientific text to be translated into Latin. It may be the first time that Arabic algebra was mentioned in a Latin publication. Bar Hiya also compiled an important encyclopedia of mathematics.

The period of great literary production in Spanish Jewish history ended with the career of Moses Maimonides (1138–1204), who fell victim to the Almohad invasions of Spain and Morocco after 1147. Contemporary with the end of this era of symbiosis and relative well-being, he was widely recognized during his lifetime as a jurist, philosopher and community leader: his legal, medical and philosophical writings marked a great moment in the history of Jewish thought, while his legacy in The Guide for the Preplexed was the subject of much comment and controversy for generations.

One of the communities of the Jewish diaspora in al-Andalus that obtained the greatest legal recognition in the Middle Ages was precisely that of Lucena,[22] a city in the region of Cordoba which, according to one of R. Natronai’s answers “was a place of Israel where many Israelites lived“, to the point of calling it Alisana al-yahud (Lucena of the Jews), due to the proportionally remarkable presence of Jews. This Jewish exclusiveness of the population of Lucena is proverbial.

Rabí Menahem ben Aarón (1312-1385) states in his book Provisions for the Way that the whole city was jewish and the Arab geographer Al Idrisi (1100 – 1165) [23] confirms this. Thanks to the memoirs of the last Ziri king of Granada, Abd Allah, published by Levi-Provençal, [24] we know that the Muslims sometimes sent a military garrison to Lucena and that there was an official or leader of the Jews, put in place by Abd Allah, called Ibn Maymun, father-in-law of Abu Rabi and treasurer of Abd Allah’s grandfather. However, we must reasonably assume that in Lucena the Jews coexisted with a contingent of Muslims and Mozarabs, probably less, although any attempt to present population figures is impossible due to the lack of documents.

The Rabbinical Academy of Lucena: Lucena had a famous rabbinical academy, of which we have abundant literary testimonies. Created in the image of the famous Jewish academies of Babylon, we do not know exactly how it was configured, but we know its importance thanks to written documents. It was able to enjoy an enormous influence and prestige, judging by the large number of illustrious visitors it received and eminent Jews who lived there:

– Moses Ibn Ezra, born in Granada around 1055, probably spent his youth in Lucena, since he himself says that he was a disciple of Yishaq ibn Gayyat in that city, an illustrious poet from Lucena;

– Yehuda ha Leví, one of the most prestigious Spanish-Hebrew poets of the eleventh century Spanish century, born in Tudela around 1070;

– Abrahán ibn Ezra, also from Tudela, born around 1089, a poet in contact with the most important Jewish poets of the time, the first to open up to the poetic themes of the Arabs, making appear in his poems realistic themes, of the daily life, beggars or card players, games of chance and chess; but he was also a liturgical poet with more than five hundred poems of synagogue, whose poetry contains a strong neo-platonic influence. He was not only a poet, he also wrote generally brief treatises on grammatical questions, biblical commentaries, mathematics biblical commentaries, astronomy, astrology, philosophy, which opened the doors of the world of Arab culture to European Jews;

– Samuel ibn Nagrela, born in Cordoba around 993 where he lived until the troubles of 1033, moving then to Malaga and Granada, and reaching the most elevated positions of the court of Granada with King Badis;

– Rabbi Yishaq ibn Gayyat the great Jewish master and poet from Lucena;

– R. Isaac ben Yaaqob al-Fasí (the one from Fez);

– or, how can we not mention him, the illustrious rabbi of the Talmudic academy of Lucena Me’ir ben Yosef ibn Migash, son and disciple of the famous rabbi Yosef ben Meir ha-levi ibn Migash.

The rabbinical academy of Lucena had to be closed with the arrival of the Almohads and Yosef ibn Migash had to flee with his family to Toledo according to Abrahan ibn Daud in the book Sefer haqabbalah.[25] The Dictionary of Jewish Authors of al-Andalus, published in the series “Studies of the Hebrew Culture” of the Editions El Almendro de Córdoba, cites thirteen other outstanding personalities who were distinguished by their culture in poetry, philology, translation, Talmud, Halachic Talmud, halaká and Jewish philosophy.

Jewish Cordoba

Cordoba, the home of Maimonides, was the largest Andalusian juderia under the Arab Caliphate of Abd ar-Rahman III. Under Muslim rule, the Jewish community lived in harmony with the conquerors who, in order to economize their reduced armies, entrusted the Jews with the administration of Seville and Cordoba.

The history of the Jewish community of Cordoba follows that of the Arab occupation and the Almohad and Almoravid invasions which limited the freedoms granted to the Jews when they did not massacre them, causing the community to flee to Granada. Nevertheless, the period from the 10th to the 12th century was the golden age of Sephardic culture in Spain.

In 1236 Ferdinand II took over the city and granted a number of privileges to the Jews but demanded a tax of 30 gold coins each year. Under the reign of Ferdinand III, violence began and reached its peak with the preaching of 1391 and numerous forced conversions. In 1492, the community complied with the decree of the Catholic Kings and emigrated in large part to Portugal and North Africa.

The Jewish quarter was situated near the mosque and the episcopal palace. The names of the squares and streets, given in the 19th century to the quarter allude to the rich cultural past: the square of Maimonides, of Judah Levi and of Tiberias, etc.

The Judería, the old Jewish quarter, extends around the old mosque-cathedral. Walls surround this maze of alleys and passages. In the 10th century, the Sephardic Jewish community of Cordoba was the largest in the Iberian world. It contributed to the cultural influence and prosperity of the city.

The Calleja del Pañuelo (Alley of the Handkerchief) is an alley that is 75 cm wide at its narrowest point. It leads to the square of the same name, one of the smallest squares in the world, which is very cute under its tree whose foliage tickles the walls.

A little further on, there is a small 13th century synagogue, a real pearl of Mudejar style. The walls bear inscriptions in Hebrew, once covered with plaster after the expulsion of the Jews in the 15th century. It was built, or rebuilt, in 1315 according to the inscriptions on the building. It is the only surviving synagogue in Andalusia, and one of three in Spain (the other two are in Toledo). The synagogue was later used as a hospital, the headquarters of the guild of shoemakers, and a school.

Synagogue of Cordoba

In 1884, the Synagogue of Cordoba was immediately declared a historical monument and restored. It is accessed through a small patio and a modest door highlighted by a brick arch. The interior, of Mudejar style, has a square shape (6 m by 6 m, approximately). The decoration, based on vegetal motifs, is very rich. It is accompanied by inscriptions, especially around the aron ha-Kodesh: quotations from Isaac Moheb ben Efraim, who is said to have completed this temple in 1315, and extracts from the Book of Psalms written in red on a blue background. It is, after Toledo, the most spectacular symbol of the Jewish presence in Spain. The building has been declared a Unesco World Heritage Site since 1994.

You can follow Professor Mohamed Chtatou on Twitter: @Ayurinu

End notes:

[1] Cf. P. Pitkanen. Central Sanctuary and Centralization of Worship in Ancient Israel. Piscataway, New Jersey, USA : Gorgias Press, 2004.

Cf. J. J. M. Roberts. The Bible and the Ancient Near East: Collected Essays. University Park, Pennsylvania: Eisenbrauns, 2002.

[2] Sefarad or Jewish Spain: The term “Sefarad” appears in the Bible, Obadiah, XX: “…and the exiles of this legion of the children of Israel were spread out from Canaan to Zarephath, and the exiles spread out in Sefarad will possess the cities of the Negev” (translation by the French Rabbinate, Paris, Colbo, 1994). Since the end of the eighth century, the term “Sefarad” has traditionally referred to Spain and Spanish Jews. By extension, it was applied to all the Jews of the communities around the Mediterranean.

[3] Julian II of Toledo (Spanish: San Julián de Toledo; Latin: Julianus Toletanus), born in Toledo around 642, was an archbishop, scholar, theologian, poet, and historian of Toledo, capital of the Visigothic kingdom of Spain, from his consecration on January 29, 680, to his death on March 6, 690. Primate of Spain, he is celebrated on March 6.

Cf. Collins, Roger. “Julian of Toledo and the Education of Kings in Late Seventh-Century Spain.” Law, Culture and Regionalism in Early Medieval Spain. Variorum, 1992: 1–22.

[4] From the 15th century onwards, the Marranos were Jews from the Iberian Peninsula and its colonies (Spain, Portugal, Latin America) who converted to Catholicism and continued to practice their religion in secret. The word “marranos” is a term of contempt that equates conversos with pigs when they are suspected of remaining faithful to Judaism. The word “Marrano” or “Marranism” has lost its pejorative connotations and is now used in historiography.

Cf. Yovel, Yirmiyahu. The Other Within: The Marranos: Split Identity and Emerging Modernity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

[5] The Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba (Arabic: خلافة قرطبة / ḵhilāfat qurṭuba) was a Muslim Iberian state ruled by the Umayyad dynasty of Córdoba that also dominated parts of North Africa. Succeeding the Emirate of Córdoba (756-929) with Córdoba as its capital, it lasted until 1031. The period, characterized by an expansion of trade and culture, saw the construction of masterpieces of al-Andalus architecture. In January 929, the Amir of Cordoba Abd ar-Rahman III proclaimed himself Caliph of Cordoba. He was a member of the Umayyad dynasty, which had held the title of Amir of Cordoba since 756. The caliphate disintegrated during a civil war (the fitna of al-Andalus) between the descendants of the last caliph, Hisham II, and the successors of his hajib (court official), al-Mansur. In 1031, after years of infighting, it fractured into a number of independent Muslim taifa (kingdoms).

Cf. Simon Barton. A history of Spain. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

[6] Ibn Hawqal writes in the ninth century “Spain is a peninsula that touches the small continent (i.e. Europe) on the side of Galicia and France: it is part of the whole of the Maghreb (Ibn Hauqal. Configuration de la terre (Kitab surat al-ard). Tr. by J. H. Kramers and. G. Wiet. Beirut, 1964, p. 58). One people predominates in this Europe, the Franks (Ifrandja). Among the categories of infidels close to Spain there is no people more numerous than the Franks” (Ibn Hauqal, 1964, p. 110). To the north, in the ocean, a mysterious people is seen: the Normans, who manage to carry out raids to Spain. Detached from the continent, several islands are known, including Brittany (understand Britain) and Ireland. North of the Tagus, things are not so simple, there are certainly the Franks (in Provence and Catalonia) but also the Galicians, the inhabitants of the region of Huesca (in Arabic Ghalidjashkash) and the Basques. A people appears as a neighbor of the Franks, the Burgundians. Continuing towards Italy (whose name almost never appears), we arrive at the Lombards (Source: Jean-Charles Ducène, “L’Europe dans la cartographie arabe médiévale”, Belgeo, 3-4 | 2008, 251-268.)

[7] The Mozarabs is a modern historical term for the Iberian Christians who lived under Muslim rule in Al-Andalus following the conquest of the Christian Visigoth Kingdom by the Umayyad Caliphate.

Cf. Torrejón, Leopoldo Peñarroja. Cristianos bajo el islam: los mozárabes hasta la reconquista de Valencia, Madrid : Credos, 1993.

[8] Mark Cohen. Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Did Muslims and Jews in the Middle Ages cohabit in a peaceful “interfaith utopia”? Or were Jews under Muslim rule persecuted, much as they were in Christian lands? Rejecting both polemically charged ideas as myths, Mark Cohen offers a systematic comparison of Jewish life in medieval Islam and Christendom–and the first in-depth explanation of why medieval Islamic-Jewish relations, though not utopic, were less confrontational and violent than those between Christians and Jews in the West. Under Crescent and Cross has been translated into Turkish, Hebrew, German, Arabic, French, and Spanish, and its historic message continues to be relevant across continents and time. This updated edition, which contains an important new introduction and afterword by the author, serves as a great companion to the original.

[9] Mohamed Chtatou. “Ibn Rochd (Averroès), l’homme de tous les savoirs, “ Oumma dated December 14, 2020. https://oumma.com/ibn-rochd-averroes-lhomme-de-tous-les-savoirs/

[10] Naima Daoudi. La poésie hébrai͏̈que d’amour en Andalousie à l’âge d’or et ses rapports avec la poésie arabe d’amour. Thèse en Études hébraïques soutenue en 2001, Paris 8.

[11] Mark Cohen. “The “Golden Age” of Jewish-Muslim Relations, “Princeton University Press, p. 50. http://assets.press.princeton.edu/chapters/p10098.pdf

[12] Esperanza Alphonso. Islamic Culture Through Jewish Eyes: Al-Andalus from the Tenth to Twelfth Century. Milton Park, Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, England, UK: Routledge, 2010.

Islamic Culture Through Jewish Eyes analyzes the attitude towards Muslims, Islam, and Islamic culture as presented in sources written by Jewish authors in the Iberian Peninsula between the tenth and the twelfth centuries. By bringing the Jewish attitude towards the “other” into sharper focus, this book sets out to explore a largely overlooked and neglected question – the shifting ways in which Jewish authors constructed communal identity of Muslims and Islamic culture, and how these views changed overtime.

[13] Moses Maimonides. Epistle to Yemen: and Introduction to Chelek. The Arabic original and the three Hebrew versions, edited from manuscripts with introduction by Abraham S. Halkin and English translation by Boaz Cohen. New York : American Academy for Jewish Research, 1952.

[14] Zachary Hampel, Anjelica Lyman, Jonathon Moss, and Eliana Schreier. “Sepharidic Art and the Ways it Keeps Sephardic Culture Alive, “storymaps.arcgis.com dated December 19, 2019. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/5efb4d57333944178ec7c3ecd5092ea4

[15] The Granada Massacre took place in 1066, in Granada, when a Muslim mob stormed the royal palace of Granada, in the Taifa of Granada1, and crucified the Jewish vizier Joseph ibn the Nagrela, and massacred the city’s Jewish population. On December 30, 1066, a Muslim mob stormed the royal palace in Granada, crucified the Jewish vizier, Joseph ibn Nagrela, and massacred most of the city’s Jewish population. 1500 Jewish families, representing about 4000 people, disappeared in one day. A rumor spread that Joseph intended to kill King Badis al-Mouzaffar, and hand over the kingdom to the Al-Moutasim (Arab tribe) of Almeira, with whom the king was at war, and then to kill Al-Moutasim, and seize the throne himself.

Cf. Richard Gottheil, and Meyer Kayserling. “Nagdela (Nagrela), Abu Husain Joseph Ibn, “Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906 ed.

[16] https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=1e203fa29a114828b87c623387ee8b04

[17] Lewis, Bernard (1987) [1984]. The Jews of Islam. Princeton New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 54.

[18] Ibid. pp. 44–45.

[19] Janssen, Loes. “Abū Isḥāq’s Ode against the Jews and the Massacre of 1066 CE in Granada.” Leiden University, Leiden University, 2016: 1–62.

[20] Spanish statesman, grammarian, poet, and Talmudist; born at Cordova 993; died at Granada 1055. His father, who was a native of Merida, gave him a thorough education. Samuel studied rabbinical literature under Enoch, Hebrew language and grammar under the father of Hebrew philology, Judah Ḥayyuj, and Arabic, Latin, and Berber under various non-Jewish masters. In 1013, in consequence of the civil war and the conquest of Cordova by the Berber chieftain Sulaiman, Samuel, like many other Jews, was compelled to emigrate. He settled in the port of Malaga, where he started a small business, at the same time devoting his leisure to Talmudic and literary studies. Samuel possessed great talent for Arabic calligraphy; and this caused a change in his fortunes. A confidential slave of the vizier Abu al-Ḳasim ibn al-‘Arif often employed Samuel to write his letters. Some of these happened to fall into the hands of the vizier, who was so struck by their linguistic and calligraphic skill that he expressed a desire to make the acquaintance of the writer. Samuel was brought to the palace, and was forthwith engaged by the vizier as his private secretary. The former soon discovered in Samuel a highly gifted statesman, and allowed himself to be guided by his secretary’s counsels in all the affairs of state. In 1027 the vizier fell ill, and on his death-bed confessed to King Ḥabus, who had expressed his sorrow at losing such an able statesman, that his successful undertakings had been mainly due to his Jewish secretary. Being free from all race prejudices, Ḥabus raised Samuel to the dignity of vizier, and entrusted him with the conduct of his diplomatic and military affairs. (Joseph Jacobs, Isaac Broydé. “Samuel Ha-Nagid (Samuel Haleviben Joseph Ibn Nagdela). https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13132-samuel-ha-nagid-samuel-haleviben-joseph-ibn-nagdela

[21] (Hebrew: אברהם בן מאיר אבן עזרא Avraham ben Meïr ibn Ezra sometimes read Even Ezra, Arabic Abu Isḥaḳ Ibrahim ibn al-Majid ibn Ezra) was an Andalusian rabbi of the twelfth century (Tudele, circa 1092 – Calahorra, circa 1167). A grammarian, translator, poet, exegete, philosopher, mathematician and astronomer, he is considered one of the most prominent medieval rabbinic authorities. The life of Abraham ibn Ezra can be divided into two periods: in the first, Abraham ibn Ezra built a reputation as a poet and thinker in his native Spain. There he assiduously frequented the most prestigious scholars of his time, including Joseph ibn Tzaddik, Judah Halevi, with whom Abraham ibn Ezra is said to have travelled to the communities of North Africa. The latter praises him as a religious philosopher (mutakallim) and an eloquent man, while a young contemporary, Abraham ibn Dawd, calls him, at the end of his chronicle, the last great man to have made Spanish Judaism proud, and a great poet, who “strengthened the hands of Israel with poems and words of consolation. ”

Cf. Carmi, T. (ed.), The Penguin book of Hebrew verse. London: Penguin Classics, 2006.

[22] https://redjuderias.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Lucena-2-marzo.pdf

[23] Mohamed Chtatou. “Etude – Ach-Charif al-Idrissi, le maître géographe du Moyen Age, “ Article 19 dated March 23, 2021. https://article19.ma/accueil/archives/141086

“ Ach-Charif al-Idrissi, concepteur de la première carte du monde, “ Oumma dated March 28, 2021. https://oumma.com/ach-charif-al-idrissi-concepteur-de-la-premiere-carte-du-monde/

[24] Évariste Lévi-Provencal. “Les Mémoires” de ‘Abd Allah, dernier roi ziride de Grenade, Fragments publiés d’après le manuscrit de la Bibliothèque d’al Qarawiyin à Fès avec une introduction francaise,” Al-Andalus 3 (1935): 245.

[25] Sefer ha-Qabbalah (Hebrew: ספר הקבלה, “Book of Tradition“) was a book written by Abraham ibn Daud around 1160–1161. The book is a response to Karaitic attacks against the historical legitimacy of rabbinic Judaism, and contains, among other items, the controversial tale of the kidnapping by pirates of four great rabbinic scholars from Babylonian academies, whose subsequent ransoming by Jewish communities around the Mediterranean accounts for the transmission of scholarly legitimacy to the rabbis of Jewish centers in North Africa and Spain. In terms of chronology, Sefer ha-Qabbalah continues where the Iggeret of Rabbi Sherira Gaon leaves off, adding invaluable historical anecdotes not found elsewhere. The Sefer ha-Qabbalah puts the compilation of the Mishnah by Rabbi Judah HaNasi in year 500 of the Seleucid Era (corresponding to 189 CE). At the time, the term “Kabbalah” simply meant “tradition”. It had not yet assumed the mythical and esoteric connotations for which it is now known. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sefer_ha-Qabbalah)