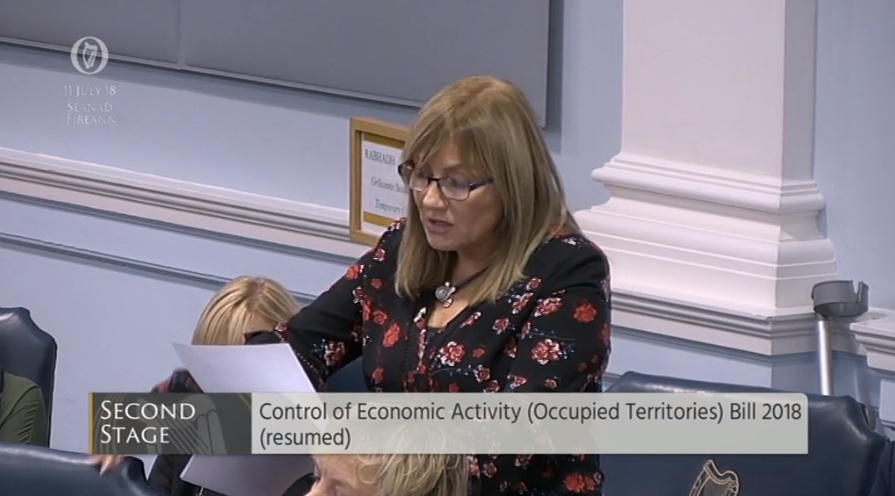

Reading the transcript of the debate that took place in the Irish Senate on July 11 before that body voted, by 25-20, to criminalize commercial relations with Jewish communities in the West Bank, I was struck by how the arguments that were traded fell neatly into one of two categories.

Category one: Those who believe that a boycott of Israel is a necessary moral undertaking and seek to introduce such a policy through legislation. Category two: Those who believe that a boycott of Israel is a necessary moral undertaking, but do not agree that enshrining such a policy through legislation is the right way to go about it.

Here are some illustrations of those arguments. Speaking in favor of category one, Sen. Niall Ó Donnghaile of the nationalist Sinn Fein Party invoked no less a figure than Nelson Mandela—who, incidentally, never once described Israel as an “apartheid state”—as he urged his colleagues to consider “what is happening in Palestine and to look at the will of the House and the majority of Irish people, who want to see us take this mode of solidarity.”

Something approaching a counter-argument was offered by Sen. Terry Leyden of the opposition Fianna Fáil Party, on behalf of category two. “I would certainly boycott products coming from occupied territories sold by the Israelis on the international market, but it is a different thing for a state to involve itself directly in this area,” said Leyden. “I advise caution.”

Leyden elaborated on his advice with several sensible, practical reasons, including one so grave that you have to wonder why no other Irish politician is apparently worried about it, at a time when the potential impact of Brexit from the European Union is already casting a dark shadow over Ireland’s economy. “In 2017 we exported $868 million worth of goods to Israel, from where we imported $63 million worth of goods,” Leyden explained, in a bid to persuade his colleagues that many hundreds of jobs in Ireland are at stake.

“Boycotts are serious,” Leyden continued, before adding, “I do not recall a Bill being introduced here when South Africa had apartheid.” When it came to addressing the rank hypocrisy that underpins the boycott of Israel, that final observation was about as far as the debate was willing to go.

Indeed, opponents of the bill were so nervous about being seen to defend Israel that they resorted to every other argument available, including opening themselves up to caricature and lampoonery in the media. “I have spent hours trying to build relationships with people who will be involved in decision making that can bring about peace—Palestinians, Americans, Israelis and others in Jordan, Egypt, Cyprus and many other neighbouring countries,” pleaded Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney, of the ruling Fine Gael Party, as he made the case for a ‘no’ vote. “I have spent a substantial amount of taxpayers’ money funding my travel in these endeavors.”

These “endeavors,” said Coveney, were aimed at rectifying the “deep injustice” that has been imposed upon the Palestinians “for decades.” And it was crystal-clear from the wider debate—whether the speaker spoke in favor or against the legislation—that Ireland’s Senate was in near universal agreement that this injustice had been imposed by Israel alone.

It is this notion of Israel as conceived in “original sin,” with the Palestinians cast as the Christ-like victim, that binds this “soft” version of the BDS campaign, which ostensibly targets only Jewish communities in the West Bank and eastern Jerusalem, with the more familiar “hard” version that targets everything and everyone that is Israeli, or that is linked to Israel in some positive way, as most Diaspora Jews are. It is the consequence of a worldview that dismisses the Jewish nation in Israel as a foreign interloper—like the English settlers who reaped the rewards of Oliver Cromwell’s brutal conquest of Ireland in the 17th century, or the Boers in South Africa who placed the yoke of apartheid on the black majority during the 20th.

That the realization of Jewish sovereignty in Israel should be associated with these earlier outrages is nothing new. For nearly a century, the struggle for the autonomy and independence of the Middle East’s non-Arab or non-Muslim minorities—Jews, Kurds and Copts, among them—has been ignored by Westerners in thrall to the myth that satisfying Palestinian demands against Israel will bring peace and prosperity to the region in general.

From there, it is but a short step to an embrace of some form of boycott, along with an unquestioning acceptance of the anti-Zionist ideology that underpins such a campaign. And as Ireland shows us, those who argue against a boycott can still share the same prejudiced assumptions as those in favor of it.

As it stands, the country that will be most damaged by an Irish boycott of Israel will be Ireland itself. Read the debate for yourselves, and see how many Irish politicians are willing to sacrifice the jobs and livelihoods of Irish citizens for the gesture politics of boycotting Israel.

Common sense may yet prevail. If it does, none of us should be surprised when Irish politicians explain their retreat as the consequence of “Zionist” pressure and American bullying. After all, what other explanation could there be?