Two major news stories to hit the headlines in Germany this month focused rather strikingly on negative depictions of Jews in works of art, raising once more the question of whether these visual displays need to be contextualized and explained, or whether they should be removed from public view altogether.

What’s really interesting is that the works of art in question are separated from each other by more than 700 years, with one example from the 14th century and the other from this one. In the first case, the offending artwork can be viewed upon the edifice of a medieval church, while in the second case, the battleground—not a term I would use lightly, but appropriate here—is a cutting-edge contemporary art show that is mounted in Germany every five years.

The two cases I’m referring to involve, respectively, a virulently anti-Jewish sculpture that was affixed to the outer walls of the Stadtkirche church in the medieval city of Wittenberg in 1305 (the same city where, more than 200 years later, the Protestant reformer Martin Luther delivered his violently anti-Jewish sermons) and a mural exhibited at the Documenta art festival in Kassel, long-established as one of the highlights in the contemporary art calendar.

The “Judensau” (“female Jewish pig”) sculpture at the Wittenberg church is frankly revolting. It shows a group of Jews on their knees suckling the teats of a pig alongside the nonsensical words “Vom Schem Hamphoras,” an insulting corruption of one of the names for God in the Jewish faith. Earlier this month, a federal appeals court ruled against a plaintiff who sought to have the sculpture removed from the church because of its viciously anti-Jewish character.

In contrast to the “Judensau” in Wittenberg, the “People’s Justice” mural was quickly covered over once the offending images were identified and then removed from the show entirely. It’s worth unpacking these two decisions to establish whether these responses—maintaining one work of art in place but getting rid of the other one—were the correct ones.

As disturbing as the “Judensau” is an image, the debate over what to do about it has been calm and reasoned when compared to the angry exchanges regarding the Documenta 15 art show. In its ruling against plaintiff Michael Dullman, a 79-year-old German Jew, the Federal Court of Justice determined that there was no need to remove the sculpture from the church’s outer wall as, since 1988, an accompanying memorial plaque aimed at visitors to the church had situated the “Judensau” as part of the trajectory of German anti-Semitism that culminated in the Holocaust.

The Central Council of German Jews largely concurred with the decision, although it argued that the current memorial does not amount to “an unequivocal condemnation of the sculpture.” Yet this shortcoming shouldn’t trigger demands for its removal; rather, what’s needed is a clearer and stronger explanation of what this appalling image represents. Instead of censoring important historical relics, the argument goes, we should leave them in place and use them as an opportunity to educate the wider public about the dangers of anti-Semitism.

Why would this same principle not apply to a work of art created much more recently? At the Documenta festival, the decision was taken to remove the “People’s Justice” mural altogether on account of its anti-Semitic iconography. There are some important differences between the two cases which explains why, in the case of the Documenta festival, the only credible option was to take the mural out of sight.

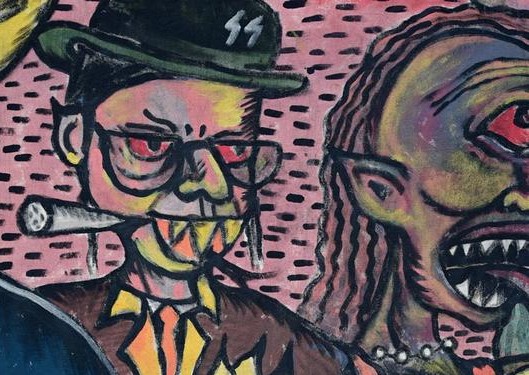

The first obvious difference is that the “Judensau” is presented to the public as a particularly shameful episode in the long history of Jewish persecution in Germany. There is no endorsement of the sculpture, officially or otherwise; as the judge in the legal case argued, with a contextualizing display alongside the sculpture, the “Judensau” is transformed from a “monument to shame” into a “memorial.” But the mural was offered to the public to win both their admiration for its artistic merit and, perhaps more importantly, their empathy with the suffering of the Indonesian people under Suharto that it depicts.

So, what do you do when a work of art presented as the authentic voice of the “Global South”—the theme of the current Documenta festival—also contains demonizing images of Jews? Sadly, the response of too many people confronted with these thorny issues is to remain silent or to pretend that the work of art isn’t really pushing hatred of Jews, but hatred of “capitalism,” “imperialism,” “Zionism,” “corruption” or some other codeword.

Because the anti-Semitic images in the mural are so obvious and crude, there wasn’t much of a debate to be had anyway. The real question is why the realization that struck everyone involved in the “Judensau” dispute—that the sculpture itself is a horror, even if there are disagreements about what to do with it—didn’t manifest with the Documenta organizers until the scandal over a mural that contained a contemporary rendition of the “Judensau” had already erupted.

Some will say that the row over anti-Semitism at Documenta—going far beyond the mural into the pro-BDS sympathies of its Indonesian curators, and their invitations to Palestinian groups trading in similarly anti-Semitic tropes—merely proves that more needs to be done to educate people about anti-Semitism. Critically, that involves not just the ability to identify Jew-hatred, but to speak out it against it regardless of the context in which it appears. In Germany, the land of the Holocaust, apparently, that is still too big of an ask.