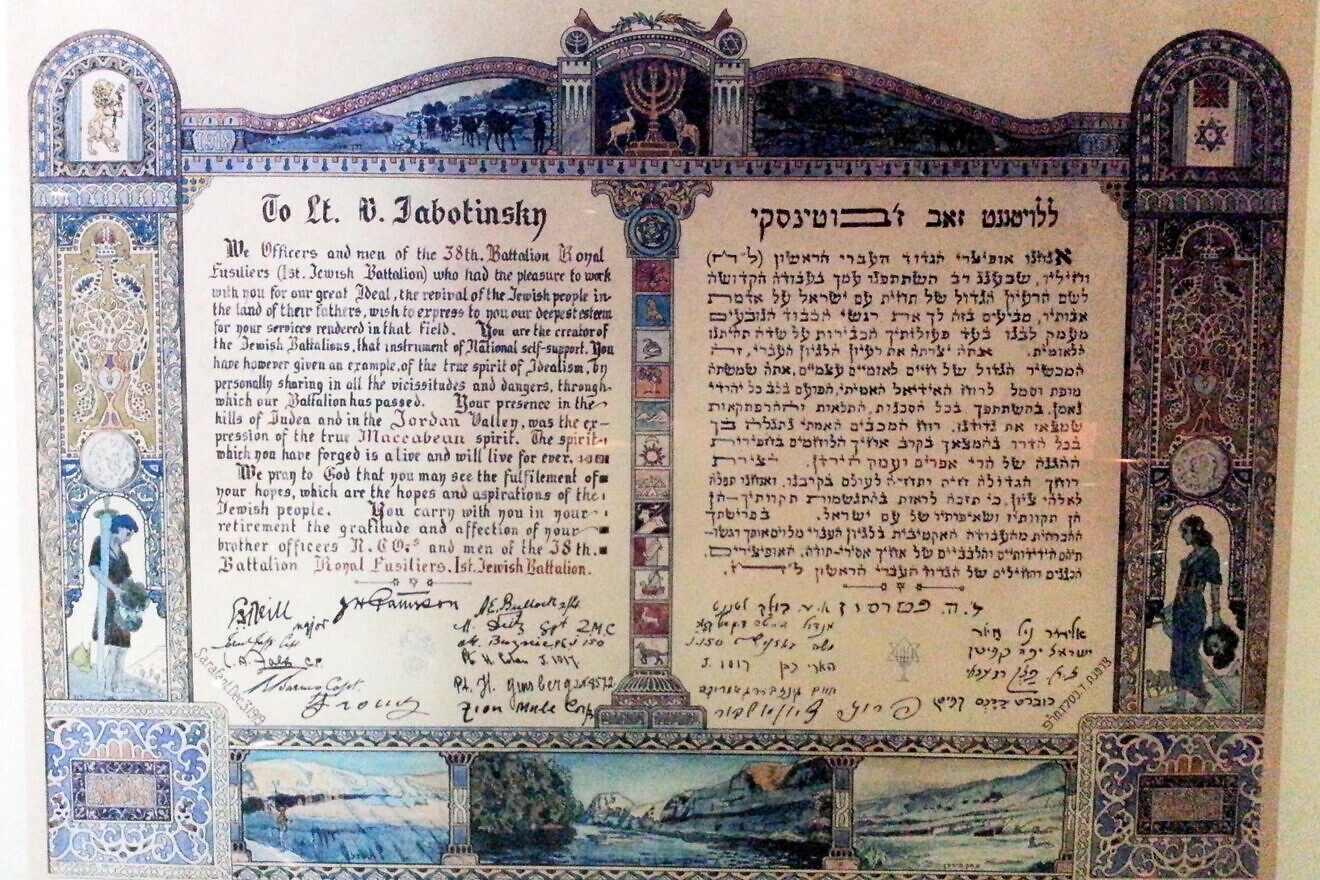

This week a century and one year ago, Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s article “The Iron Wall” was published in the Russian-language weekly, Razsvet, on Nov. 4 in Berlin. So famous has it become that last month, The New York Times highlighted its influence on Israel’s security doctrine on Oct. 18 by noting that “the Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky articulated an idea that has come to define the way Israelis protect their country.”

Moreover, so well-known has it become that many pro-Arab propagandists—Jewish and others—quote from it to justify their claims. For them, it confirms that there exists a “Palestinian people” and that Zionism was indeed a “colonization project.”

However, a second part of that essay appeared the following week, on Nov. 11. It was titled “The Ethics of the Iron Wall.” In it, Jabotinsky zeros in not on the need for an impenetrable barrier that would provide security from Arab aggression, but on the justness of his political solution within the future Jewish state and his ideas on accommodating the Arab minority.

In doing so, Jabotinsky pens political, social and moral wisdoms that serve us well not only today but in many varied situations.

For Jabotinsky, the fundamental approach is that of the Helsingfors Program, which was formulated in 1906. What he envisioned for the Arabs was what he demanded that Russia adopt for its Jews. That included status as a national minority to provide the Arabs in the reconstituted Jewish state with cultural, material and political means for a sound national life. Israel-to-be was envisaged as a liberalized, democratic country with autonomous rights for its non-Jews, who would exercise their political rights as well as cultural, educational and even administrative autonomy.

He later expanded and detailed his outlook in 1940 as part of his last book, The War and the Jew, in the chapter “The Arab Angle Undramatized.” Yet for Jabotinsky, the responsibility for an equitable outcome, for both Jews and Arabs, rested with the latter: “Even if they [the Arabs] believed in good-neighborly coexistence, the first and main question remains: do they want to have ‘neighbors,’ even good ones, within the country they consider their own.”

Jabotinsky was not one to disallow Arabs any agency or release them from a commitment to share in the formation of a state that sought to grant a minority the fullest of rights without disregarding the conflict in the background. After all, murderous riots had already taken place in 1920 and 1921 in Jerusalem and Jaffa.

He then turned his attention to Jews overexcited to placate the Arabs to the extent that they would be endangering the Zionist project. He wrote:

“The political naivety of the Jew is fabulous and incredible: he does not understand the simple rule that one should never ‘go to meet’ someone who does not want to go to meet you.”

He provided an example:

“Jewish publicists and politicians, even nationalists, considered it their duty to support the autonomous aspirations of their enemies in every way: for, you see, autonomy is a sacred thing … we consider it our duty, as soon as we hear the ‘Marseillaise,’ to freeze at attention and shout hurray even if this melody was played by Haman himself and Jewish bones were cracking in his barrel organ. We consider this to be political morality. This is not morality, but depravity. Human society is built on reciprocity: take away reciprocity, and the right becomes a lie.”

He added in a somber, if not depressive tone:

“The world must be a world of mutual responsibility. If we live, then everyone does so equally. And if we die, then everyone will so equally. There are no ethics according to which the greedy are supposed to eat their fill, and the modest to perish under a fence.”

He considered the tendency to agree to concessions by his rival, Chaim Weizmann, to be “particularly sad.” For Jabotinsky:

“The scope of concessions to Arab nationalism that we can agree to without killing Zionism is extremely modest. We cannot give up the desire for a Jewish majority, we cannot allow Arab supervision of our immigration, we cannot allow a parliament with an Arab majority, and we will never join any Arab federation.”

In today’s atmosphere of the cries to eliminate Zionism, to boycott Israel, to hound it and its supporters out of academic, cultural and diplomatic forums, Jabotinsky’s final summation of more than a century ago is remarkable:

“If there is a landless people in the world [the Jews], for them even the dream of a national home is an immoral dream. The landless must remain landless forever; all the land in the world has already been distributed, and that is the end. This is what ‘ethics’ demands. In our case, this ethic ‘looks’ especially curious … when homeless Jewry demands Palestine for itself, this turns out to be ‘immoral’, because the natives find this inconvenient for themselves.

“Such ethics belong among cannibals, not in the civilized world. The land does not belong to those who have too much of it, but to those who have none. … Truth, carried out by force, does not cease to be the sacred truth. This is the only objectively possible Arab policy for us. There will be time to talk about an agreement later.”

Jabotinsky then ends with a philosophical “Iron Wall”:

“All sorts of catchwords are used against Zionism. People invoke Democracy, majority rule, national self-determination … the Arabs being at present the majority in Palestine, have the right of self-determination, and may therefore insist that Palestine must remain an Arab country. Democracy and self-determination are sacred principles, but sacred principles like the Name of the Lord must not be used in vain, to bolster up a swindle, to conceal injustice.

“The principle of self-determination does not mean that if someone has seized a stretch of land, it must remain in his possession for all time, and that he who was forcibly ejected from his land must always remain homeless.”

This 1923 article rounds out Jabotinsky’s thinking on what has turned out today to be the most basic challenge facing Israel and its defenders, which is the moral right of Jews to return to their homeland despite it being occupied by Arabs. His insight and analysis all remain applicable and, I would insist, appropriate even after the passing of 101 years.

Whereas in his first section the main, but not only, issue is the external security threat, this second section outlines an internal manageable relationship between Jews and Arabs.

Realizing that a century on, Zionism’s opponents have not changed may be desponding. Still, Jabotinsky’s approach—in its assertiveness and forthrightness—still provides an uplifting antidote to the current onslaughts on the right of Jews to our national identity and statehood.