In his important book Power and Powerlessness in Jewish History, the historian David Biale noted that the very first ancient Egyptian reference to the nation of Israel was a brutal announcement of its destruction.

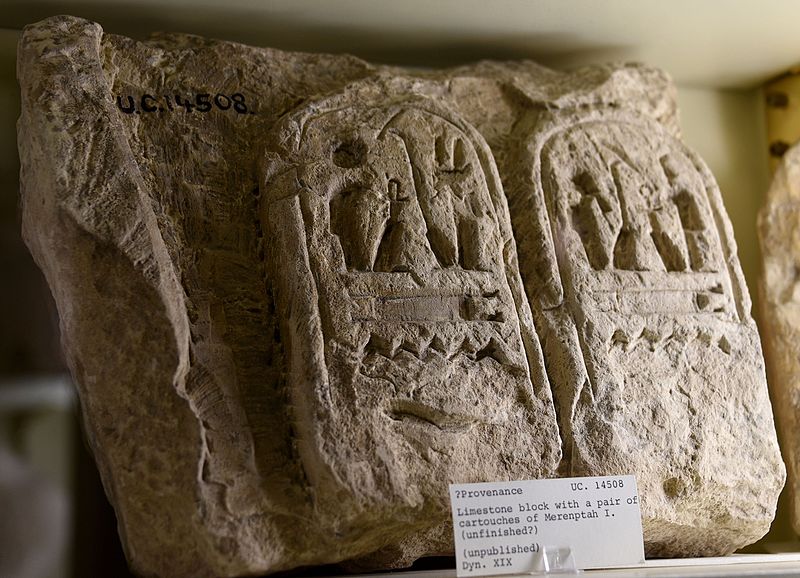

“In the stele of Pharaoh Merneptah from the late thirteen century BCE, the name of Israel appears in a list of conquered nations,” wrote Biale. “Israel, the Pharaoh declares in one of the greatest ironies in recorded history, is ‘laid waste and his seed is no more.’ ” Observed Biale: “In the same century when most historians believe the Israelites left Egypt and began to develop into a nation, the ruler of the greatest ancient empire declared them utterly destroyed.”

But in the week that Jews celebrate Pesach, there is something particularly resonant about an Egyptian Pharaoh’s claim to have successfully carried out what these days would be called a genocide. That’s partly because, in the irony pointed out by Biale, Egypt was the territory in which the Canaanite tribes actually crystallized into the nation of Israel, whose distinctiveness was shaped by their relationship to the land of Israel and their fealty to the Mosaic Law.

In addition, Merneptah’s stele is an early indication of where the Jews stood in the power rankings of nations; fairly low down, their fate tied above all to the machinations of the other, larger nations around them. As Biale says, the extent of the independence of the Israelites was nearly always determined by forces larger than themselves. “Only under [the reign of Kings] David and Solomon,” he wrote, “was full national sovereignty established by taking advantage of a temporary decline in imperial power.”

This combination of an inherited, structural weakness, along with a stubborn determination to survive, gave rise to all sorts of notions about the place of the Jewish people in the pantheon of nations. “All things are mortal but the Jews; all other forces pass, but he remains,” wrote Mark Twain in an admiring essay of solidarity published by Harper’s magazine in 1899—suggesting that not only were the Jews in an elect relationship with God, but also with human history. This, of course, was the polar opposite of Pharaoh Merneptah’s pronouncement; far from having their seed eliminated, according to Twain, the Jews are fated to be an eternal, physical presence on this earth.

Twain’s words belonged to a time when it was fashionable to conceive of history as a tortured process with an inevitable outcome; for some, this was the “Kingdom of God”; for others, it was the emergence of an all-powerful (and overpowering) modern state; and for others still, it was the promise of equality in a socialist paradise. The philosophers and political theorists who believed that history was geared towards a specific end also had pretty firm views on the place of the Jews in that process. It’s fair to say that the balance of opinion lay more with Pharaoh Merneptah than with Mark Twain; among nationalists, there was a strong conviction that the Jews needed to be actively swept away, while among Socialists and Communists, there was a supreme confidence that the Jews would disappear as a distinct group once capitalism was overthrown (with a bit of help, as the Soviet Union would graphically demonstrate, from the authorities.)

The very fact that the Jews have been the focus of a multitude of wrong-headed predictions, frequently motivated by malice, is a reflection of their relative powerlessness throughout history. This meant that other people’s opinions about who the Jews were, and their consequent decision about where the Jews were headed, counted for far more than anything the Jews did. However the Jews shaped their internal world, it was the world outside of their communities that determined their destiny.

It was this wretched imbalance that political Zionism sought to correct. Yet however much we conceive of Zionism as a modern Jewish nationalist movement, it likely wouldn’t have succeeded among the Jews themselves without the weight of Jewish tradition behind it.

If there is a seminal event in that tradition, it is the exodus from Egypt—the point at which the nation called Israel comes into being. As Jews tell it, it isn’t simply a story of survival. Nor is it a story that lends much credibility to the various prognostications of outside observers about what lay in store for the Jews. It is, rather, an occasion when we step onto history’s stage on our own terms, and in our own words. To my mind, that’s what makes Pesach special.

Ben Cohen is a New York City-based journalist and author who writes a weekly column on Jewish and international affairs for JNS.