Part XI

Identity Crisis of German Jewry

The price of emancipation required Jews to suppress every external vestige of their traditions, customs, and culture, which had an adverse effect on their self-esteem and self-image, asserts historian Ismar Schorsch. Yet to combat antisemitism at the end of the century required Jews to publicly affirm their Jewish identity. If they explicitly engaged in self-defense, they would be viewed as having violated the terms of their admission to German society.

“Civic responsibilities must not suffer on account of religious practice,” is how political activist lawyer Emil Lehmann suggested Jews navigate this delicate balance. His attitude explains the conflicting feelings of hesitation, reluctance and aversion German Jews experienced in deciding how to respond to antisemitism.

At the beginning of the German Empire in 1871, German Jews did not have a national network of organizations to assist small communities that were in need of assistance due to the financial crisis, Schorsch said.

Deutsch-Israelitischer Gemeindebund

In 1869, the Deutsch-Israelitischer Gemeindebund (DIGB—union of German Jewish communities) was established in Leipzig to provide a forum for local communities to air their pressing concerns relating to the “legal status” of German Jews. In 1882, the Gemeindebund moved to Berlin.

Political Parties Committed To Racial Antisemitism

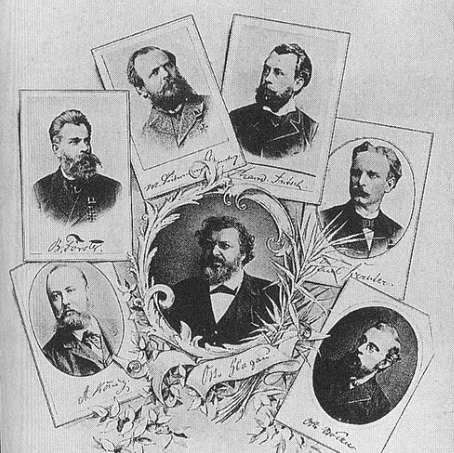

During the time that Adolf Stöcker founded the Christian Social Party in1878, there were a number of new political parties that emerged specifically devoted to racial antisemitism, Schorsch notes. These included Ernest Henric’s Social Reich Party (1880); Alexander Pinkert’s German Reform Party in Dresden; and Bernhard Förster and Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg’s the German People’s Association.

During 1880 and 1881, Förster, Sonnenberg and Henrici circulated a petition called “The Emancipation of the German People from the Yoke of Jewish Rule,” demanding the immigration of Jews be either suspended or limited, barring them from serving in important government positions, restoring a Jewish census and ensuring the Christian character of the Volksschule, the universal, free and compulsory educational institution. The organizations collected signatures and sent copies to mayors, judges, editors and local and district government officials throughout Germany.

This campaign compelled the liberals to respond, Schorsch said. The liberal intellectuals were the most supportive of the Jews, historian Uriel Tal said. They were the educated class and the liberal professions, especially those involved in creating social values and transmitting them to the next generation, including the general population.

They viewed preserving the right of “autonomous self-determination” as “the indefeasible right of all men and all citizens, including Jews, by virtue of natural law,” Tal states. From the beginning of the 19th century, this principle provided the foundation for the emancipation of all segments of German citizens, as well as for the Jews, “over and against the dominant Christian society.”

On Nov. 13 and 14, 1880, the liberals published a declaration in the major Berlin newspapers denouncing this uncontrolled animosity, which jeopardized the exigent process of national and religious reconciliation, Schorsch said. Seventy-three venerated Christians signed the petition.

In addition to Maximilian von Forckenbeck, the lord mayor of Berlin, and Nobel Prize laureate Theodor Mommsen, there were 17 university professors, 15 members of the Berlin Chamber of Commerce, 10 municipal officials, nine lawyers, six legislators, five high-level bureaucrats, four school directors, three Evangelical clergy and two physicians who signed the petition.

Despite this very public rebuke against the antisemitic petition, the petition was delivered on April 13, 1881, with a declared total of 225,000 names to Otto von Bismarck, chancellor of the German Empire. But there was no ideological consistency in the “Berlin Movement,” as this antisemitic movement was called, asserts historian Shumel Ettinger. It was a confusing mixture of “conservative romantics and racial radicals.” When the Reichstag elections were held that year, not even one candidate on the antisemite list was elected.

Responding to Social Unrest

During the end of 1880 and the first months of 1881, the leaders of the Gemeindebund became increasingly hesitant about publicly confronting the infectious nature of the social unrest, Schorsch said. In July 1881, the board agreed that antisemitism had not succeeded in establishing support, except in a number of politically and religiously conservative areas like Berlin, Breslau, Dresden and specific districts in Westphalia and Pomerania. Yet the antisemitic movement had significant influence because of its close relationship with officials within the government.

The verbal assaults ultimately led to a series of anti-Jewish incidents, Schorsch said. On April 18, 1881, an old synagogue in Neustettin (Pomerania) was burned to the ground. Antisemites charged the small Jewish community of Neustettin with torching the synagogue to collect the insurance money to build a new one. In July, antisemitic riots erupted in the city and quickly expanded to other communities in the provinces of West Prussia, Pomerania and Brandenburg. On this occasion, the government intervened resolutely. The rioters were apprehended and penalized, and the cities were directed to compensate their Jewish citizens. All antisemitic speeches in Pomerania and West Prussia were forbidden by order of the Minister of the Interior.

Attempts by the Crown Prince of Germany and Christian liberals to repudiate the antisemitism did not halt the unrest. This convinced the Gemeindebund that Jews should not approach the kaiser, chancellor, Reichstag or any other member of the government and not participate in any future deliberations in the legislatures. The possibility of gaining a positive outcome looked quite bleak. They asked that the problem not be discussed in any public forums, because attention would likely “distort the dimensions of the movement,” Schorsch said.

Dr. Alex Grobman is the senior resident scholar at the John C. Danforth Society, a member of the Council of Scholars for Peace in the Middle East, and on the advisory board of the National Christian Leadership Conference of Israel (NCLCI). He has an MA and PhD in contemporary Jewish history from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.