For much of the 20th century, there was a “Jewish seat” in the U.S. Supreme Court. It was first occupied by Justice Louis Brandeis, who served from 1916 to 1939. He was succeeded by Justice Felix Frankfurter from 1939 to 1962 and then Justice Arthur Goldberg from 1962 to 1965. When Goldberg resigned to become U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations at the behest of President Lyndon Johnson (one of the worst decisions ever made by any justice and one that Goldberg lived to regret), he was replaced by yet another Jew, Justice Abe Fortas, who served until 1969 when he was forced to resign due to an ethics investigation.

Though there was a six-year period when there were two Jews on the court—the more conservative Justice Benjamin Cardozo, who had been appointed by President Herbert Hoover served alongside Brandeis from 1932 to 1938 when he died—the tradition of a reserved place for a Jewish justice was during those decades a tradition that presidents choose to respect. Or at least they did until Fortas, a Johnson crony whom he had hoped to make chief justice, ran afoul of ethics scrutiny. His successor, named by President Richard Nixon, was Justice Harry Blackmun, who ended the streak of Jewish justices. It would not be until President Bill Clinton tapped Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg for the court that another Jew would be one of the nine judges at the top of the American judicial pyramid.

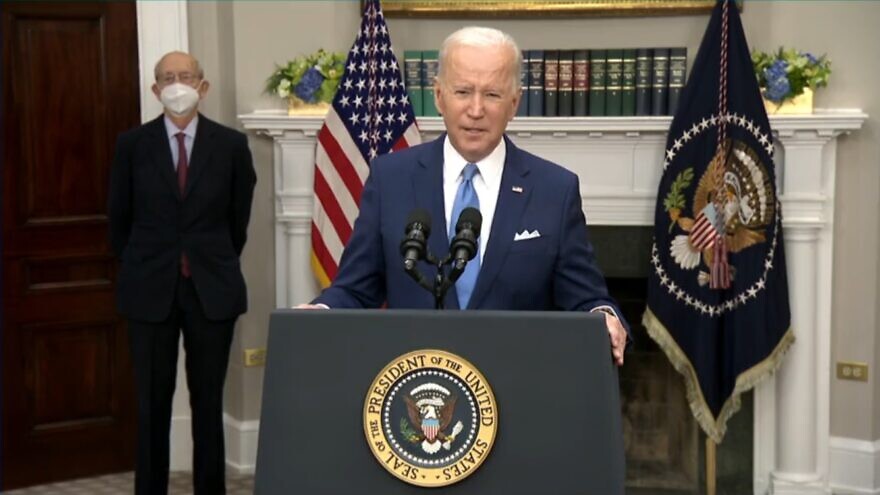

This gives President Joe Biden the opportunity to nominate a justice for the court. It comes after a campaign by liberal media and legal figures to pressure Breyer to step down now while the Democrats still have a majority in the Senate as well as control of the White House, something that may no longer be true after the midterm elections this fall.

That will make it possible for Biden to appoint a liberal to the court to replace Breyer. That won’t alter the current ideological tilt of the court in which there are six conservatives and three liberals, though Chief Justice John Roberts sometimes joins the trio on the left (which currently consists of Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor and Breyer), in cases where, unlike the majority of those litigated in the court, unanimity is not possible.

Mindful of both that assurance and the demands of satisfying his political base, especially in the post-Black Lives Matter movement era in which considerations of race have become paramount to liberals, Biden has announced that he will keep his word.

It’s not clear how many plausible candidates fit the criteria. But the assumption is that Biden is likely to be able to pick a black female judge who is capable of gaining the support of the 50 Democrats in the Senate, as well as—assuming she is not too radical—perhaps a Republican or two with Vice President Kamala Harris waiting to break the tie in favor of Biden’s nominee if necessary.

As was true of the tradition of the “Jewish seat” that prevailed for so long, since 1916, the belief that the court’s membership should not solely consist of white Christian males has become mainstream thinking. Nor is there anything wrong in principle with the notion that the members of the court should represent, as far as it is possible, a broad cross-section of Americans.

But the problem here is not so much the quest for diversity as it is with the idea that every federal appointment must be made with affirmative-action-style quotas in mind.

If the court is now widely perceived as a political forum, it’s not so much because of the activist impulses of the judges as it is because of the way the political system has changed. A dysfunctional Congress has long since abdicated much of its lawmaking responsibilities to the administrative state staffed by presidential appointees and career bureaucrats in the various government departments and agencies. It is that unelected group that is making most of the laws and regulations that currently govern American society and business. That has left it to the courts—and the Supreme Court, in particular—to act as the sole check on the executive branch, making it a sort of super-legislature in judicial garb.

And it is that shift that has also turned every Supreme Court nomination into a barroom brawl. Beginning with the way Democrats—led by Biden, then the Senate Judiciary Committee chair—turned the name of the distinguished conservative judge and thinker Robert Bork into a verb in 1987, nominees have been both demonized and subjected to unsubstantiated accusations of various kinds. Though the confirmations of Ginsburg, Sotomayor and Kagan were not marked by partisan hysteria, just about every other one since Bork has been a donnybrook.

Justice Clarence Thomas was subjected to a charge of sexual harassment that he likened to a “high-tech lynching.” Worse, his fitness for the court was questioned because President George H.W. Bush felt constrained to nominate a replacement for Justice Thurgood Marshall, the court’s first African-American, who would fit into the same racial slot. In his memoir, My Grandfather’s Son, Thomas speaks of his resentment about the way he was treated after graduating from Yale Law School when potential employers assumed he was there as a result of affirmative action rather than merit. The same was true of the way Thomas has been treated since he was confirmed, with liberal commentators denigrating one of the court’s most profound legal thinkers for holding views they think a black man shouldn’t have. They speak of him with the sort of condescension they’d call racist if it was directed at a liberal.

We’re a long way past the point when the Supreme nine were universally accepted as the best of the best in the legal field, an assumption that the careers of distinguished legal thinkers like Brandeis, Cardozo and Frankfurter more than justified. Yet even if the person that Biden picks is given an easier time than recent Republican nominees, the increasing acceptance of the idea that gender and especially race, rather than individual merit, is the most important thing about a person is a trend that we should regard with alarm.

The occupants of the old “Jewish seat” were generally thought of as having been so outstanding that they made it to the court in spite of being a member of a small religious minority group rather than because of it. Nor did anyone think of Ginsburg’s appointment—or that of Breyer or Kagan—having been the result of any desire on a president wishing to score points with the Jews. With Breyer’s resignation, the number of Jews on the court will likely be back to one from a high of three when Ginsburg served with him and Kagan. Yet even if eventually Kagan is also replaced by a non-Jew, that won’t signal anything terrible for her co-religionists.

As is the case with college admissions, the desire to promote diversity inevitably gives way to quotas in which some racial or ethnic groups are winners and some are losers, throwing the values of meritocracy—so essential to democracy as well as to the rights of minorities—to the winds. Preserving a meritocratic society is far more important than dubious and ultimately unattainable notions about racial or gender balance. No matter who sits on the Supreme Court, the consequences of such quotas, no matter how well-intended, are something all Americans should fear.