What’s going on in Wadi Hummus? Behind the tumult and the Supreme Court ruling that approved Israel’s demolition of 12 buildings in Wadi Hummus on July 22 stands the murky and unusual legal status of the place and its residents.

Wadi Hummus, an unofficial extension of the Sur Baher neighborhood in eastern Jerusalem, is not included in the municipal territory of Jerusalem but is adjacent to it.

Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration have not been applied to Wadi Hummus as they have been to thousands of other acres in the former territory of Jordanian Jerusalem and villages in the Jerusalem area. These were “annexed,” of course, after 1967 and became part of Israeli Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty—unlike Wadi Hummus, which remained outside the “annexation” borders.

The situation in Wadi Hummus, which is in southern Jerusalem, is the opposite of the situation in the Shuafat refugee camp and Kafr Aqab in northern Jerusalem. In the north, Shuafat and Kafr Aqab have remained outside the security fence even though they are part of municipal Jerusalem, and even though Israeli sovereignty applies to them.

In the south, in Wadi Hummus, the situation is the opposite: Wadi Hummus, which is not part of Jerusalem and not under Israeli sovereignty, was enclosed, at the request of the local Arab residents, within the security fence (the “Jerusalem belt”). The residents even appealed to the Supreme Court on the matter.

The two Jerusalem locations in the north situated outside the fence and the non-Jerusalem location in the south enclosed within it have suffered over the years from an absence of government, from neglect, criminality, poverty and a lack of effective building supervision. All three areas have become a kind of no-man’s-land, “stuck” between Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

In Wadi Hummus, an area of about 100 acres, an estimated 5,000 people now reside, comprising one-third to one-fourth of the residents of Sur Baher. Over the years, the area has become an eastern expansion of Sur Baher, a neighborhood in which construction is relatively restricted. From the standpoint of the Sur Baher residents, the extensive construction in Wadi Hummus offers a solution for their housing shortage.

The decision to build the security fence was made about 17 years ago, during the administration of Ariel Sharon. Such a barrier was deemed necessary due to frequent terrorist attacks throughout Israel and particularly in Jerusalem. The route of the fence, which cuts through Jerusalem, was determined based both on security considerations and serving “Israeli interests.”

The length of the fence was planned to be 104 miles, but many sections are yet to be built. However, a majority of the sections along or close to the jurisdictional boundary of Jerusalem have been completed.

In Sur Baher, the state planned to run the security fence along the jurisdictional boundary, but vigorous lobbying activity, including an appeal to the Supreme Court, by residents who opposed detaching Wadi Hummus from Sur Baher changed that decision. The result was that Wadi Hummus was included within the route, even though it is not part of Jerusalem.

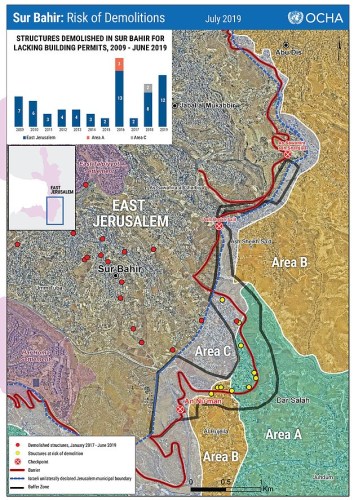

Some of the Wadi Hummus residents are originally from Sur Baher and hold Israeli residency cards. Others are from the West Bank and are not Israeli residents. The result is a legal and bureaucratic imbroglio in which Wadi Hummus, a tract of only a few tens of acres, is enclosed within the security fence, is not an official part of Jerusalem and includes areas A, B and C of the West Bank.

According to the Oslo Accords, in Area A, security and civilian control belong to the Palestinian Authority; in Area B, security control belongs to Israel and civilian control to the Palestinian Authority; while in Area C, official security and civilian control belong to Israel.

Judiciary Confusion

Over the years, the courts, too, have had trouble with this mix. For example, on the same day in 2009, two Jerusalem District Court judges handed down contradictory rulings pertaining to the Wadi Hummus residents. One judge decided that the residents should be granted the Israeli residency rights, while the other determined that they should not.

In an additional ruling, the Supreme Court assented to the state’s position and laid down that the Wadi Hummus residents who held P.A. documents were not entitled to the status of permanent Jerusalem residents and hence had to renew their residency permits for Wadi Hummus every six months.

In actuality, the Jerusalem municipality—to which Wadi Hummus does not officially belong—provides the neighborhood with minimal services, such as garbage removal, but has no planning and licensing authority there. Yet the P.A., in whose territory most of Wadi Hummus is located, has trouble communicating with residents, who are on the other side of the fence in a kind of Israeli enclave.

At the end of 2011, about six years after the security fence was built in the area, the army issued an order prohibiting construction in a strip extending 100 to 300 meters on both sides of the fence. According to the NGO B’Tselem and other sources, “This order was needed to create an open buffer that [the army] required for its activity since the Wadi Hummus area is prone to illegal entry from the West Bank to Jerusalem.

“According to IDF data at the time the order was issued, there were already 134 structures in the area designated as prohibited for building. Since then, tens of additional structures have been built, and as of mid-2019 there were already 231.”

Some of these buildings have multiple stories, some are mere skeletons. They were built at a distance of tens of meters from the fence and scattered among the areas defined as A, B and C.

At the end of 2016, the IDF demolished three buildings in the neighborhood and announced its intention to raze another 15. In 2017, residents appealed to the Supreme Court. They claimed that most of them had received building permits from the P.A., which was formally responsible for the area in which the structures were built. While the case was being argued in court, the state announced that four of the buildings would be only partially dismantled and that the demolition orders for two others would be canceled.

A few months ago, Supreme Court justices Menachem Mazuz, Uzi Vogelman and Isaac Amit rejected the residents’ appeal and allowed the state to carry out the demolitions.

In his ruling, Justice Mazuz wrote that “the authority of the military commander to apply his authority for security reasons, including imposing restrictions on building based on military security needs, also applies to Areas A and B.”

Mazuz noted that “any building that is carried out in contravention of the order prohibiting building, even in Areas A and B, is illegal, and it is clear that a civilian permit from the Palestinian planning authorities does not detract from the authority of the military commander in this regard.”

According to Mazuz, “The petitioners sealed their own fate when they began and continued building the structures that are the object of the petitions without receiving special approval from the military commander and while ignoring the order.”

The story of Wadi Hummus, like the stories of Kafr Aqab and the Shuafat refugee camp in the north, is a stark illustration of the confusion caused by the security fence not running along Jerusalem’s municipal boundary.

In a recent report, David Koren, who served as an adviser to former Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat on eastern Jerusalem affairs, summed up the facts regarding this incongruence:

Notable enclaves outside the fence and within the municipal boundary:

- The area of Walaja in the south of the city—an area of about 120 acres that includes residences.

- A large area that includes all the neighborhoods of the Shuafat refugee camp, Ras Khamis, Ras Shehadeh and the Hashalom neighborhood. This area, of about 220 acres, is very densely built up.

- An area that includes all of Kafr Aqab, Al-Matar, Ze’ir and Kalandia in the north of the city and covers about 320 acres.

The total area of all the territories that are beyond the security fence but within the City of Jerusalem’s jurisdiction is estimated at 850 acres, and the number of residents of these territories comes to between 120,000 and 140,000.

Notable enclaves outside the municipal boundary but inside the fence:

- Har Gilo and all the land that surrounds it, which includes the entire community, in an area of about 173 acres.

- Wadi Hummus (in the vicinity of Dir al-Amud and Dir al-Muntar in the southeast of the city), about 100 acres.

- An area east of Neve Yaakov that includes about 370 acres.

The total of all land beyond the municipal border but within the fence comes to 2,394 acres. The number of Arab residents of these areas comes to about 7,000.

Nadav Shragai is a veteran Israeli journalist.

This article originally appeared on the website of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.