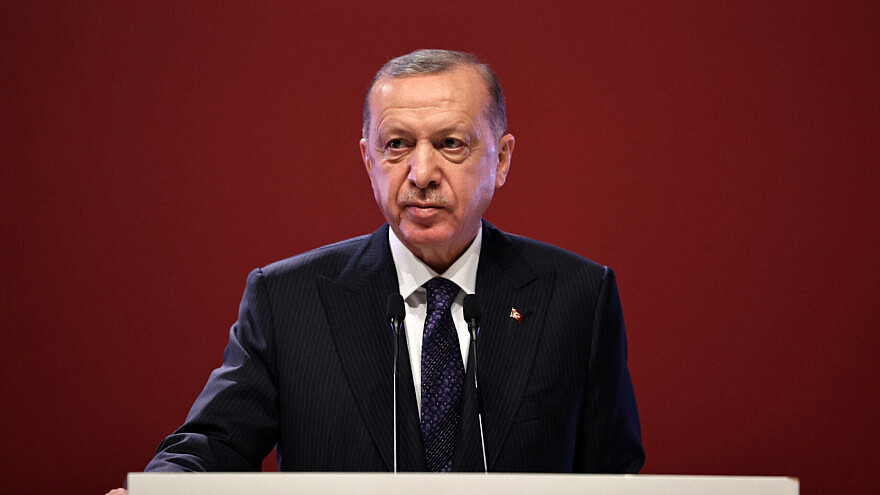

It turns out the reports on the impending end of the Erdoğan era were greatly exaggerated. Those who were hoping for a crushing defeat of the Turkish president in last week’s election had their hopes dashed as Recep Tayyip Erdoğan heads for a runoff with his main challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu on May 28. They will have to wait for nature to do its thing, as the 69-year-old leader is apparently not in great health.

Despite the polls and predictions, the advantage that Kilicdaroglu had heading into election day disappeared after the votes had finally been counted, with Erdoğan topping his rival 49.5% to 44.9%. Erdogan also managed to keep control over the parliament with his allies. Now polls show that the incumbent is likely to cruise to victory in the second round.

Some have tried to explain away this situation by claiming that Erdoğan has used his incumbency to turn Turkey into an authoritarian state that lacks checks and balances, without an independent judiciary or media. That perception has been shaped in part by the fact that his detractors have often been sent to prison, and he has used the state’s apparatuses to boost his image and win over voters.

It seems that Turkey under Erdoğan has become a partial and limited democracy, which manifests itself only once every four years in elections where the opposition has no chance of winning.

But it turns out that like in many places around the world, voters are content with the situation, having put Erdoğan in first place. The Turkish electorate wants an authoritative leader who projects strength at home and abroad and gives the people a sense of national pride and a sense of security in his leadership.

Identity politics have defined the elections. Thus, while the opposition has tried to cast its battle against the incumbent as a fight to save democracy and restore the economy, the president drove home the message that he is the guardian of the walls of Turkish nationality and Islam.

He has also tried to portray Kilicdaroglu as someone who has been prepped up by Kurdish terrorists and the West and therefore poses a threat to Turkey’s fundamental values. Kilicdaroglu is secular and belongs to the Shi’ite-Alawite minority, rather than the Sunni like the vast majority of Turks.

Most Turkish voters, especially in rural areas and poor neighborhoods in the cities, relate to the conservative, religious and nationalist message in Erdoğan’s campaign, not the liberal and Western message of his opponent. That’s why they answered his rallying cry to support him and save their country. After all, for them, Erdoğan is a hero who is their champion, fighting the fight of the average people against the rich and educated (mostly secular) elite in the establishment that dominates the big cities.

To understand just how strong this bifurcation is, just look at the voting among those in southern Turkey: They gave their support to Erdoğan despite the fact that their homes were ravaged by an earthquake because of his government’s failure to prepare for such a calamity. Meanwhile, in Ankara and Istanbul, voters sided with Kilicdaroglu, as did the Kurds in the east.

The Turks have become used to Erdoğan, and even his detractors don’t wish to return to the days when the military controlled the state, supposedly in order to safeguard democracy and Western secular values. Things are bad in Turkey but back in the day, the economy was in a much worse state. In fact, back then political opponents were persecuted and even executed.

It seems as though the world—and even Israel—has also gotten used to the president. He surely talks the talk, but he rarely walks the walk in his threats. In practice, he has managed to strike a delicate balancing act between East and West and between Russia and the United States. Above all, he has made sure not to cross any red lines.

Even when relations with Israel were at rock bottom, they were never severed: Trade and tourism flourished. So, it appears that the world also concurs with Turkish voters’ decision to go with Erdoğan, despite everything.