How would the State of Israel survive, much less thrive, in a land where water resources were so scarce?

The genius who solved this riddle was Walter Lowdermilk. Raised in the rugged, arid terrain of Arizona, Lowdermilk majored in chemistry at one college, then engineering at another. That instruction was followed by a Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford, which permitted him to study German forests. Then he worked to prevent the cycle of floods and famines faced by Chinese peasants.

These varied experiences and training prepared Lowdermilk for his life’s occupation: joining together the arts of soil conservation and water management. Those skills were further honed during his tenure with the U.S. Forest and Wildlife Service’s Soil Conservation Service.

An extended stay in British Mandate Palestine inspired his influential 1944 bestseller Palestine, Land of Promise. It presented a detailed plan for water use and land reclamation. In his book, Lowdermilk claims that the Jewish people, “demonstrated the finest reclamation of old lands that I have seen in three continents … by the application of science, industry and devotion … [they have acted against] great odds and with sacrificial devotion to the ideal of redeeming the Promised Land.”

The book sparked interest in and admiration for the pioneering settlers, and, along with Lowdermilk’s meetings with American leaders, it convinced a broad swath of the Western intelligentsia that a great and populous country could be built by Jews amid the “human-made” deserts of Palestine. Integral to this, he explained, was use of the Jordan River to provide drinking water and electricity, and the Litani River to irrigate the Negev.

Lowdermilk even outlined a visionary and now a possible proposal to build a canal for hydroelectric power extending from the Mediterranean to the Dead Sea. In all, he set forth what has been called “the Lowdermilk Plan”: an outline for the creation of the nation’s water system.

He also criticized the White Paper of 1939, warning that limiting Jewish immigration to Palestine would lead to massacres of Jews by Arabs.

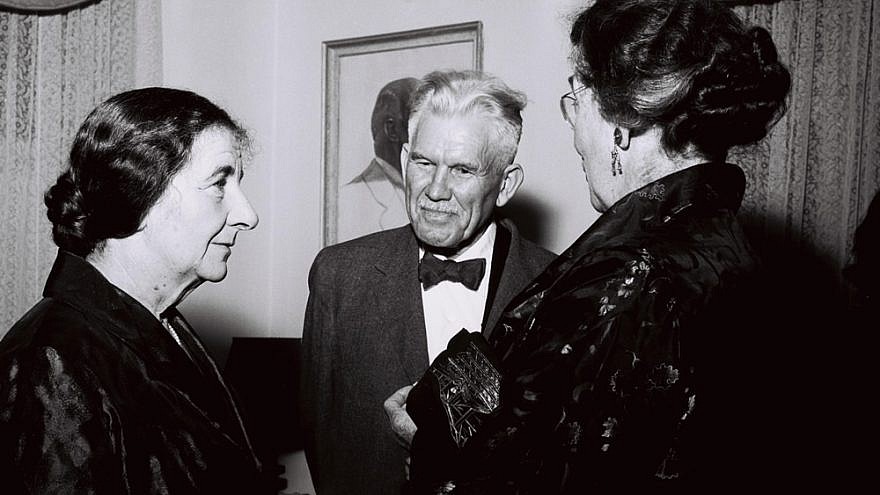

Lowdermilk returned to Israel in 1951. Now called “the father of the Israel water plan,” he stayed through 1957, guiding the setup of Israel’s Soil Conservation Service and helping to establish the Technion University’s School of Agriculture and Engineering, which was later named after him.

His writing provided impetus for the construction of the National Water Carrier. In appreciation of his many contributions to the Jewish state, Israel Minister of Development Mordecai Bentov put it best: “We don’t need powdered milk. We need Lowdermilk.”