In 2011, on one of my first trips to the United Arab Emirates, I sat in on a class taught by then-New York University president John Sexton on law and religion at NYU Abu Dhabi. It was a thrill to watch this legendary law professor take 20 Emirati students through a Talmudic reading of the Establishment Clause. But little did I know, I was about to be called to the stand.

“We have a special guest today. Yehuda, introduce yourself.” I said my name and title, explaining that I ran the Bronfman Center for Jewish Student Life at NYU in New York. “That’s not enough,” Sexton said. “They’ve never met a Jew before in their life, let alone a rabbi. We’re trying to analyze these Supreme Court cases. Can you explain to the class, briefly, what Judaism is?”

At this point, the questions came fast and furious. A rabbi in the classroom? The Establishment Clause was forgotten; Judaism became the subject of curiosity.

The Bronfman Center at NYU decided to offer the Jewish Learning Fellowship, a 10-week, non-credit course on Jewish texts, to students at NYU Abu Dhabi. We expected that between five to 10 students would sign up. More than 80 students enrolled within a few days after a student sent one single email.

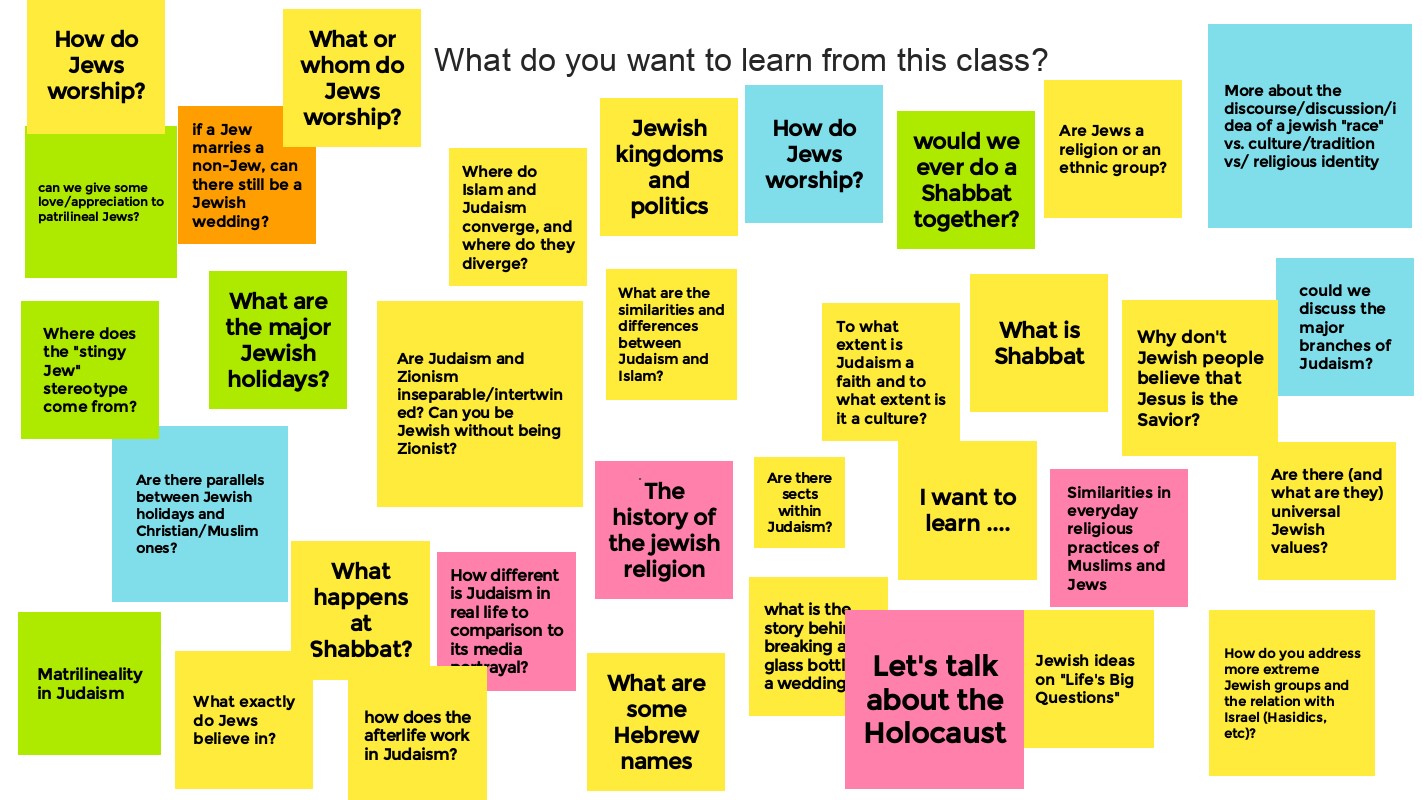

The highlight for me of every class is the “Ask the Rabbi” segment. The questions range from the most philosophical to the most practical—from questions about God and prophecy to differences in head covering. This past week in response to a question about kosher food, I walked my laptop through my meat and dairy kitchens, past the cereal box shelf and into our meat freezer. Next week, I will address a student’s question about what Jews believe about Jesus.

To be sure, we have respected the sensitivities around teaching texts of non-Islamic religions. We have made it clear that we do not aim to sow confusion in anyone’s previously held faith; we are not seeking converts. Our purpose is simply to reverse the decades of division that have planted ignorance as a hedge between Judaism and Islam.

These teaching experiences, above all others, give me hope for the region. It may sound strange to hear, but I believe that the key asset the Middle East needs in order to succeed is not oil, natural gas or a booming tourism industry; neither global finance hubs nor strong militaries. The key resource that must be carefully cultivated is intentional curiosity.

There is no time to waste, and we must also do our part. The Passover seder is at its essence an exercise in nurturing our curious instincts, as we find creative ways to prompt questions from younger members of the table, though no one is exempt:

If his son is wise and knows how to inquire, his son asks him. And if he is not wise, his wife asks him. And if even his wife is not capable of asking or if he has no wife, he asks himself. And even if two Torah scholars who know the halakhot of Passover are sitting together and there is no one else present to pose the questions, they ask each other. (Pes. 116a)

A child is deemed “wicked” if they feign curiosity. A child who does not question must be taught to ask.

Passover is the Jewish festival of curiosity. If we foster it within ourselves, we can, true to Judaism’s essence, redeem ourselves and others.

Rabbi Yehuda Sarna, NYU University Chaplain, is the Chief Rabbi of the Jewish Council of the Emirates and the Honorary Chairman of the Association of Gulf Jewish Communities.