When the late German writer Günter Grass decided, seven years ago, to publicly denounce Israel as the greatest threat to the planet’s existence, he chose the medium of poetry to do so. Starting from the observation that there was lots of fuss about Iran’s nuclear program, but none about Israel’s, Grass deemed himself the victim of “a troubling, enforced lie/leading to a likely punishment the moment it’s broken/the verdict ‘Anti-Semitism’ falls easily.”

According to Grass, the guilt the world felt at the past persecutions of the Jews, and especially the Germans, meant that there was a reluctance to speak the plain truth: “Israel’s atomic power endangers/an already fragile world peace.” Nonetheless, Grass threw himself forward as courageous enough to say just that, despite knowing in advance of the opprobrium that would be poured on his head by the political guardians of the Western guilt complex (i.e., the Jews). “I’ve broken my silence/because I’m sick of the West’s hypocrisy,” he declared. “And I hope too that many may be freed/from their silence.”

The furor that followed Omar’s comment was largely unhelpful. There were far too many patronizing calls on the congresswoman to apologize for what she said—as if she’d naively strayed into language about the influence of pro-Israel forces on Capitol Hill that most Jews find anti-Semitic.

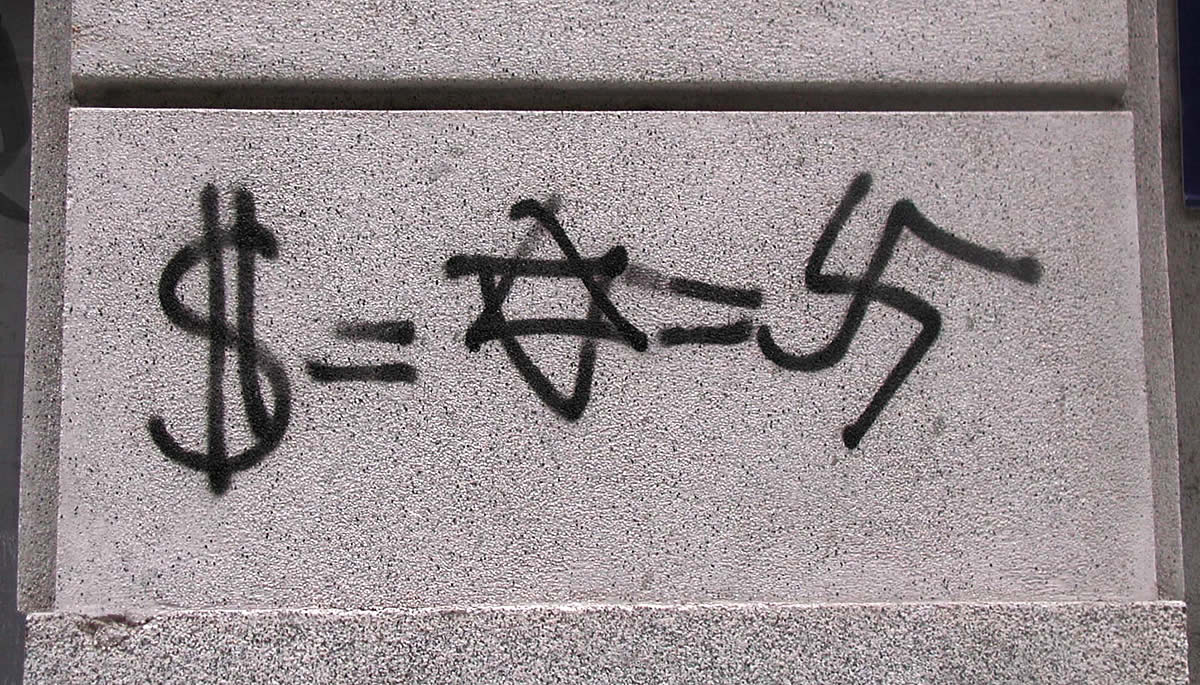

To the contrary, Omar’s statement reflected the enduring nature of one specific anti-Semitic trope in a country that, at least when compared with Europe, pretty much despises them. That trope, which feeds on the 250-year dispute about the role of special interests in American politics, concentrates on the mobilization of American Jewish political and financial influence on behalf of Israel, at all costs and under any conditions.

Omar is not the first U.S. legislator to have trafficked in this image, which is rooted in the anti-Semitic idea that Jewish power is, by definition, financially driven, tribal in interest and ruthless in the effects that it has upon non-Jews. James Abourezk—a Democrat from South Dakota who became the first Arab-American elected to the U.S. Senate—was a consistent opponent of American policy in support of Israel during his tenure from 1973-79. In a 2006 interview, he gave this explanation for why legislative opposition to the U.S.-Israel alliance was so difficult to muster. “I am realistic enough to know that, because the Congress is pretty much reliant on money from radical Zionists, stopping the flow of American taxpayers’ money to Israel will not come soon,” he said. (That, incidentally, is among the more mild of the many observations that Abourezk has made about the scope of pro-Israel influence in America.)

There was also Paul Findley, a former Republican Congressman from Illinois who became a professional opponent of “Zionist interests” after he lost his bid for re-election in 1981. Although he attracted the disapproval of AIPAC and other pro-Israel groups because of his budding political relationship with the late PLO leader Yasser Arafat, Findley acknowledged that such opposition to his re-election “was only one of several factors” in his defeat. But apparently piqued by AIPAC officials bragging that they were responsible for such—a routine tactic used by political fundraisers—Findley went on to found the Council for the National Interest, whose mission is to persuade American legislators that said national interest is fatally compromised by a relationship with Israel imposed from above by powerful financial interests working on behalf of a foreign power.

Findley also wrote a book about his experience. Much like Günter Grass later on, Findley needed a touch of melodrama to sell his story, so he called it They Dare to Speak Out: People and Institutions Confront Israel’s Lobby. Alongside Findley’s story were the accounts of other U.S. officials and politicians—among them Adlai Stevenson, the Rev. Jesse Jackson and one of the original Jewish proponents of anti-Semitism in America, Dr. Alfred Lilienthal—who had run afoul of the “lobby’s” control of both policy towards and speech about the Middle East.

That ever-present threat is why, of course, one has to summon the courage to say “what must be said.” It is why one must “dare to speak out.” Above all, it clarifies why—in the words of The Israel Lobby, a notoriously flawed 2006 study by the political scientists John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt—“Congress almost always votes to endorse the lobby’s positions, and usually in overwhelming numbers.”

Now that Ilhan Omar has dared to speak out—from within the walls of the U.S. Congress, this time—some will wonder whether is a watershed moment that disrupts the close relationships that many U.S. legislators have with Israel. For my part, I am skeptical. A Gallup poll last March revealed that 74 percent of Americans retain a favorable view of Israel. The findings were “as strongly pro-Israel as at any time in Gallup’s three-decade trend,” the company noted. Despite Rep. Omar’s best efforts, the elephant in the room—American public opinion that is as warm towards Israel as the Europeans are cold—isn’t going anywhere.