Respect is always slow in coming for national leaders who are labeled as conservatives. In the United States, this has led to a dynamic by which politicians who are demonized by the left during their lifetimes are held up as virtuous examples to be emulated by the same people in subsequent decades in order to attack contemporary conservatives. That is certainly the case with Ronald Reagan, who was attacked when he was president, but is now extolled so as to diminish subsequent leaders of the GOP. But the belated recognition given to Reagan in this manner is of negligible historical value since context is always different.

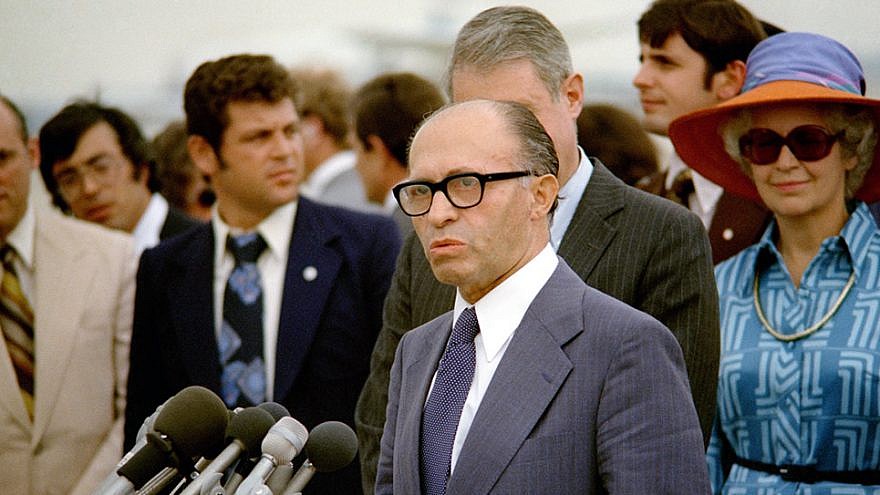

Yet the same thing has apparently happened with respect to Reagan’s counterpart in Israel: Menachem Begin. The subject of intense hatred on the part of his political opponents during his long career, Begin is now receiving his due as a member of Israel’s founding generation. Unfortunately, the motives of some of those paying homage to his memory have less to do with historical justice and more to do with efforts to paint the current head of Likud as unworthy to follow in Begin’s footsteps.

Begin has evolved from being an icon of the Jewish right to a man whose historic significance and enduring greatness have become part of the legacy of the entire country, rather than a single political movement or party. That’s a good thing—though the surest sign of this is the way his memory is being invoked as a cudgel with which to batter Netanyahu.

Netanyahu’s chief rival, the Blue and White Party’s Benny Gantz, claimed that Begin would have kicked the current prime minister out of the Likud Party. More than that, he asserted that Begin would be unwelcome in the contemporary Likud; that someone with his views would be considered “an enemy of Israel.”

Even the far-left Meretz Party is now appropriating Begin’s legacy by speaking of his advocacy for peace with Egypt, even if that debate was very different from the one about the Palestinians.

The left is also seeking to make use of Begin’s reputation as a stickler for the rule of law and his down-to-earth lifestyle to make the case that Netanyahu is unfit to walk in his footsteps. The man who was damned by Israel’s political, media and entertainment establishments as a right-wing extremist for most of his life is now a figure that today’s leftists claim to prefer to Netanyahu.

While Begin is worthy of the praise that he is belatedly receiving, the effort to portray him as the anti-Netanyahu—and the notion that the Likud of the 1970s and 80s would reject today’s version—doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

Comparing anyone from today’s Israel to those who struggled to create the Jewish state is always a losing proposition for contemporary figures. But the talk about Begin not fitting into today’s Likud is as pointless as charges that today’s Republicans wouldn’t accept Reagan. Both were products of their time and took stands on the issues as they were currently understood. Netanyahu’s judgments about Israeli politics or the country’s place in the world is a function of today’s context and challenges, not that of 1977.

While there are clear differences between the two men that do not flatter Netanyahu, not all of them favor Begin. For all of his courage, Begin knew little about financial issues, though the same can be said of most of Israel’s political leaders in his time or now. Netanyahu’s grasp of economics is one of the reasons why Israel has attained a first-world economy and relative prosperity. (To be fair, a degree from the MIT business school helps.)

The notion that Begin would have disagreed with Netanyahu’s efforts to restrain Iran, avoid Israel being forced to make dangerous concessions to the Palestinians or to give up the right of Jewish settlement in any part of the land of Israel, or even about the nation-state law, is absurd.

The same is true with respect to campaign rhetoric since Begin was never shy about lambasting his opponents in ways that were not always perfectly civil. Most of the things that are said today about Netanyahu were said about Begin with respect to democracy or peace even if their sensibilities were very different.

Begin believed that his efforts as the leader of the Irgun Zvai Leumi during the struggle for Israel’s independence—as he helped force the British out, and then avoided civil war between the Jewish right and left—eclipsed his service as prime minister in terms of importance. In that sense, nothing Netanyahu could do, no matter how long he serves as prime minister or what he achieves, will compare to Begin’s legacy.

In order to understand Begin’s importance, we need to put aside politics and facile comparisons, and recognize that what today’s Jewish world misses the most about Begin isn’t so much his ascetic lifestyle or his lawyer’s affection for parliamentary procedure as the values he embodied.

Menachem Begin was a complex figure who understood that the decisions that face the Jewish people were similarly complex. He was not so much a product of the generation of the Holocaust and Israel’s birth as he was the embodiment of the consciousness of the moral obligation to defend the Jewish people, to secure their homeland and for a stiff-necked refusal to bow to foreign pressure.

We will not see his like again because the cruel historical challenges that helped mold him are, thankfully, part of the past. If subsequent generations wish to learn from him, they should remember that he viewed his decisions in the context of Jewish history, not election cycles. That’s something today’s Israeli politicians should never forget.