Anybody who pays attention to the sorts of things honored by contemporary popular culture knows that stories about heroism are passé. But why then do we still long for them? One example comes from an incident that took place almost a century ago.

In March 1920, Arab gangs attacked the Jewish settlement of Tel Hai in the Upper Galilee. Josef Trumpeldor led the defense of the isolated farming village. He was a rare Jew who had served in the army of the Tsar and then helped lead the first contingent of Zionist Jews fighting with the British against the Turks in World War I. He returned to Russia, organized Jewish self-defense against pogroms and then headed back to Palestine, where he wound up defending newly established Jewish farming villages near the border with Lebanon.

As was fitting for a secular Jew like Trumpeldor, his words echoed those of the Roman poet Ovid’s Odes—dulce et decorum est pro patria mori (“it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”) more than any traditional Jewish text. But his sacrifice inspired generations who followed in his footsteps rebuilding and then successfully defending the Jewish homeland. Just as important, he was embraced as a hero by both the Jewish right—the Betar national youth group founded by Ze’ev Jabotinsky and later led by Menachem Begin was named for Trumpeldor—as well as by their Labor Zionist rivals on the left.

But to future generations of Israelis, the authenticity of Trumpeldor’s final utterance was called into question. He may have just cursed in Russian about his bad luck. His shaky command of Hebrew might also not have enabled him to say something so eloquent. It’s a dispute that can never be definitively settled.

More important is that many also came to doubt the validity of the sentiment behind those noble words. To the cynics of the last 20th and early 21st century, the idea of there being something glorious about bloody sacrifice for the sake of a national ideal was exactly the sort of talk that starts wars. To some, patriotism was not just old-fashioned, but also dangerous.

That is especially true for Americans who came of age after Vietnam, Watergate and countless other scandals that have robbed the nation of much of the idealism about patriotism that was once taken for granted.

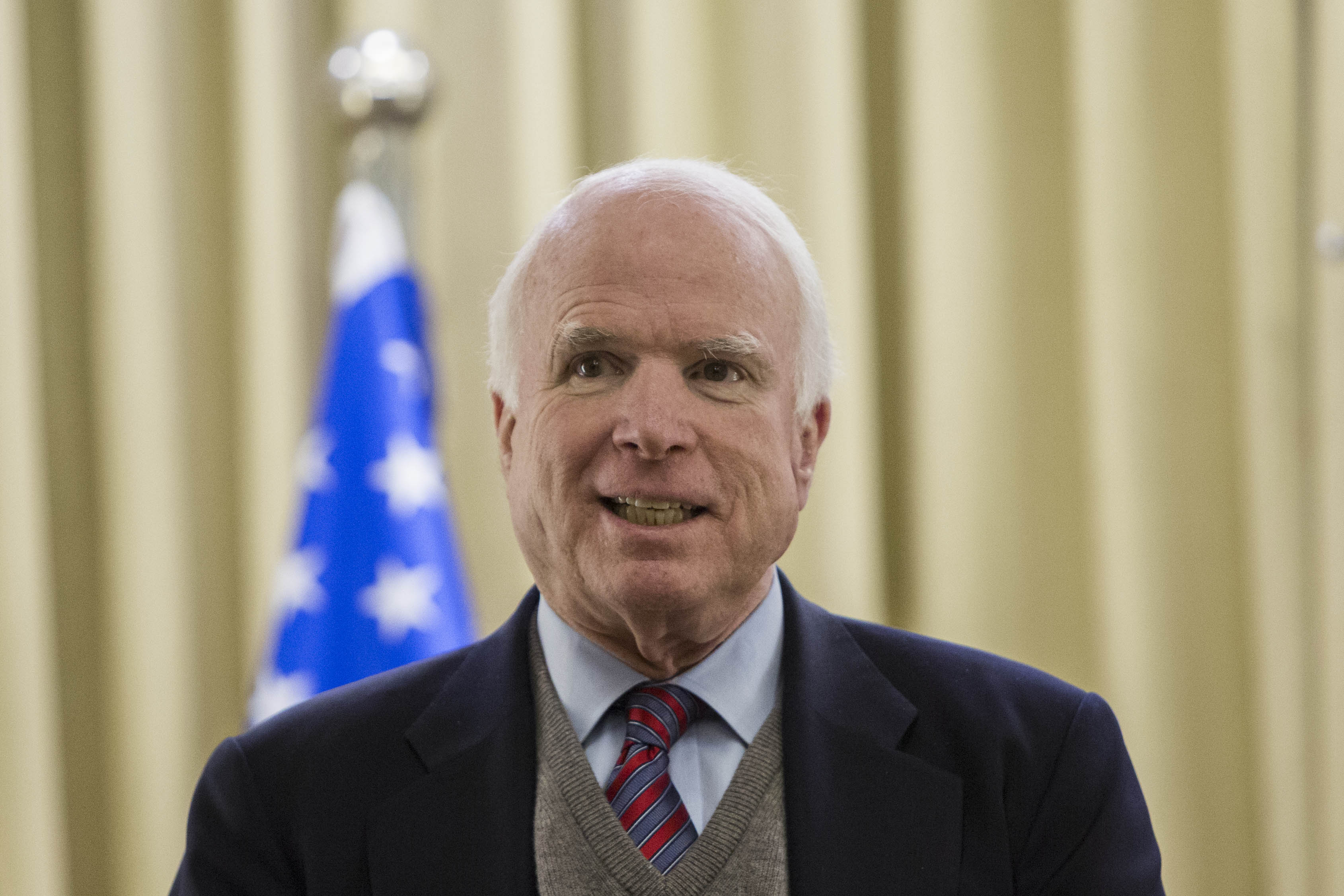

It’s in this context that we should think about the life of Sen. John McCain, who passed away this past weekend at the age of 81 after a long battle with brain cancer.

McCain was a central figure in American politics for a generation and twice unsuccessfully sought the presidency. An independent spirit, he was often an unpredictable guided missile, taking up causes that struck his fancy regardless of whether they fit in with his generally conservative approach to politics.

Sadly, in his final years, he was subjected to a torrent of abuse because of his feud with U.S. President Donald Trump, who started the spat by wrongly calling into question McCain’s status as a war hero. Some on the far right, especially on social media, even continued calling him a “traitor” after his death, though in doing so they demonstrated their own ignorance and lack of grace. That echoed the abuse he had always gotten from the far left, which viewed his unswerving support for Israel and belief in a strong U.S. foreign policy advocating American values of freedom of democracy with equal contempt.

But what is important about McCain is that he lived his life in the same spirit as Trumpeldor’s famous quotation. His was a life lived in service to his nation. There is no denying that his bravery in enduring torture and imprisonment at the hands of his North Vietnamese captors. And whether you agreed with him on every issue or not, the fact that he continued serving his country throughout the rest of his life completed a legacy that was based more on character and patriotism than anything else.

McCain mattered because unlike most politicians, his claim to office was based not so much on ideology as it was on biography. Not many U.S. presidents have been truly great men. And while we can’t be sure that he would have been a good president, the main reason he came so close to that goal was because so many thought he deserved the honor as a result of his life story. In that sense, he was very much a throwback to an earlier time in American history, when the presidency was seen more as a reward for meritorious service or heroism than a mere political contest.

We may not need presidents to be heroes, but the founders of the American republic believed that civic virtue was essential to the survival of their experiment. The manner in which Israel’s founding generation lived was a testament to the same sentiment. Cynics and those who decry even the most democratic forms of nationalism often dismiss patriotism and the idea of sacrifice for the nation. We no longer engage in hero worship of the kind that produced generations of Americans who thought George Washington never told a lie or Israelis who believed in the Zionist equivalents of that myth.

We’re right to keep even the most seemingly exemplary leaders’ feet of clay firmly in view. But we still need heroes because they are essential to perpetuating the ideals that are the foundation of American society. Nations like the United States and Israel are, after all, based on ideals more than other considerations. That’s why we need the Josef Trumpeldors and John McCains. They point the way for the rest of us towards the values to which we aspire but so often fall short.

May the senator’s memory be for a blessing.