One of presidential candidate Joe Biden’s major election promises was a U.S. return to the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA), a multilaterally negotiated agreement regarding which former President Barack Obama was enthusiastic, but from which his successor President Trump withdrew in 2018.

On Sept. 20, 2020, candidate Biden wrote: “I will offer Tehran a credible path back to diplomacy. If Iran returns to strict compliance with the nuclear deal, the United States would rejoin the agreement as a starting point for follow-on negotiation. With our allies, we will work to strengthen and extend the nuclear deal’s provisions, while also addressing other issues of concern.” Furthermore, he declared rejoining the nuclear deal as a priority for his administration.

Simply put, Biden undertook to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal as is, with no preliminary negotiations on “extending and strengthening” it or on other issues of concern. All these will be put on the table only after the United States rejoins the deal—namely, after lifting the Trump-imposed sanctions on Iran. All this, in return for Iran’s “rollback” of its violation of the deal’s provisions, such as enriching uranium beyond JCPOA-permitted levels.

Biden’s statement defines a U.S. return to the nuclear deal as a “starting point for follow-on negotiations” but leaves open the question of whether it will also be Iran’s “starting point.” Biden required no prior commitment from Iran for any “strengthening and extending” of the deal, or in fact any prior commitment to negotiate. What will President Biden do if Iran flatly refuses to consider any change in the deal or to negotiate other “issues of concern”? His statement remains mute on this question.

Yet Biden’s statement contains some criticism of the original nuclear deal. Specifically, Biden hints at weaknesses in the existing stipulations that need “strengthening.” He points out that the agreement needs to be “extended,” and that there are other “issues of concern” that need to be addressed. Some of the weaknesses of the original agreement were obvious even during its negotiation, and some became clear immediately after its conclusion and ever since.

In its Dec. 5 issue, The Economist listed three reasons why U.S. conservatives, as well as Israel and the Gulf states, are opposed to a U.S. “clean return.” First, some of the limitations on Iran have already expired or are due to expire in the next few years. Second, the exclusion of Iran’s missile program from the nuclear deal. Third, Iran’s aggression across the region and in particular its support of armed proxy militias like the Houthis in Yemen and Hezbollah in Lebanon.

In short, critics believe that a new and improved nuclear deal is required, that will extend its duration, impose limitations on Iran’s missile programs and require Iran to moderate its regional policies.

It goes without saying that a “clean return” will deprive the Biden administration of any leverage over Iran regarding negotiations on, or implementation of, any changes in the existing nuclear deal. Nevertheless, immediately after the elections, speaking as president-elect, Biden did not change his position. In an interview with Tom Friedman in The New York Times on Dec. 12, 2020, he said that “There are talks about missiles of various ranges and other matters that destabilize the region” but “that the best way to bring back a modicum of stability to the region” is “to deal with Iran’s nuclear program.” Thus, a return to the existing nuclear deal with no strings attached seems to be a cornerstone of Biden’s foreign policy.

Moreover, it stands to reason that Biden as well as his European allies will move towards Iran rapidly, under the gun of the June Iranian presidential elections. Following the elections, Iran’s incumbent President Hassan Rouhani and his foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif (the team that led the nuclear deal negotiations to its conclusion in 2015) will step down. Both have a clear motivation to see the United States rejoin the nuclear deal now, thereby restoring their prestige and public standing that was bruised by Trump’s withdrawal. While still in office, this duo is likely to speak softly and make some vague promises about future negotiations, as lip service to Biden’s election promise of returning to the nuclear deal as a “starting point.” This will provide the new U.S. president with the moral justification for a “clean return,” against critics in the United States, in Israel and in the Gulf states, including Saudi Arabia.

The June 2021 deadline results from the fact that all five contenders for Iran’s presidency belong to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Hitherto there was some semblance of a balance of power between the so-called “hardliners” and the erroneously-labeled “moderates” in Iran’s leadership. In reality, this was nothing more than a tenuous balance between the ideological-military establishment headed by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and the economic-diplomatic faction in Iran’s government that to date has nominated all of Iran’s presidents. Many of these presidents have been considered “moderate” by the West because they used more friendly language towards Western diplomats and civil society organizations. Some of them, most notably Rouhani, were willing to make some real concessions.

This tenuous balance will collapse once the ideological-military faction takes over the presidency. In somewhat simplistic media language, the “moderates” will be excluded—perhaps permanently—from Iran’s decision-making processes. It is not unlikely that an Iranian president who hails from the IRGC will flatly refuse to promise or even hint at any further negotiations once the United States has lifted sanctions. This will make it harder for Biden to justify a “clean return,” since it will not be a “starting point for follow-on negotiations.”

It should be noted that this deadline is a self-imposed target. Once an IRGC president is in power, the likelihood is very low that he will honor any commitments from the Rouhani–Zarif era. In other words, the Biden administration is rushing to return to the nuclear deal while there is still a soft-spoken Iranian president to give the United States cover for doing so; while there is still a chance to coax some vague and vacuous promises of follow-on negotiations from Rouhani and Zarif.

In fact, this “window of opportunity” may be even narrower than previously envisaged. While violating some JCPOA provisions (ever since the reimposition of U.S. sanctions), the Iranians nevertheless have been careful to adhere to two key stipulations: no enrichment beyond 3.5 percent and permitting IAEA inspectors to visit their nuclear installations. But following the killing of Iran’s top nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh in November 2020, the Iranian parliament (which essentially is an organ of the IRGC) legislated an increase in uranium enrichment levels to 20 percent and the barring of IAEA inspectors from some of their tasks.

On Jan. 2, 2021, Iran announced the resumption of 20 percent enrichment “as soon as possible.” A week later, on Jan. 9, it threatened to expel all IAEA inspectors by Feb. 21 unless sanctions are lifted by that time. Once these two measures—higher enrichment levels and the end of watchdog inspections—are implemented it will be much more difficult to roll back Iran’s transgressions.

Thus, the latest Iranian threats are obviously meant to pressure Biden into rejoining the JCPOA “cleanly,” without delay.

Motivations and obstacles on the road to rejoining the JCPOA

The eagerness of the new Democratic administration to rejoin the nuclear deal derives from a combination of contemporary liberal articles of faith and pragmatic considerations.

One typical article of faith among Western liberals is that nuclear weapons are the ultimate evil, dwarfing conventional threats. Therefore, curbing nuclear proliferation justifies “conventional” concessions. Another article of faith is that diplomacy and negotiations are the preferred tools for settling disputes and that the lack thereof inevitably leads to war. The third article of faith is the essence of the U.S. alliance with Europe. For the new U.S. administration, rejoining the nuclear deal signifies a return to the liberal camp of nations that pursue policies based on values rather than interests.

Beyond ideology, the new Biden administration has several pragmatic reasons to rejoin the JCPOA. One of the original aims of the deal was to prevent the nuclearization of other Middle Eastern countries such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Turkey. Another key aim of the deal’s architects was to craft something that was more than just another routine arms control agreement. They were after a deal that augured a “detente” between the West and Iran; a new path of moderation for Iran, leading it to transition from a “rogue” state to a peaceful and respectable member of the international community.

President Obama, in his “Implementation Day” statement in January 2016, called on the Iranian people to take “the opportunity to begin building new ties with the world. We have a rare chance to pursue a new path—a different, better future that delivers progress for both our peoples and the wider world. That’s the opportunity before the Iranian people. We need to take advantage of that.”

As several U.S. analysts have pointed out, from Obama’s perspective, the details of the deal did not matter. What mattered was the very existence of an agreement, however indirect, between the United States and Iran; an agreement its architects hoped would become the first step in the “reconstruction” of Iran and its reintegration into the global community, expecting that this would soften Tehran’s policies on other matters.

Taking Biden at his word, the rush to rejoin the nuclear deal stems from the desire to “return a measure of stability to the Middle East,” which probably means Biden’s concern regarding an Israeli preemptive attack on Iran’s nuclear installations, and in the long run regarding the nuclearization of more Middle Eastern countries. That a U.S. reversal may destabilize the Middle East apparently is not being considered by Biden administration officials.

Still, the “clean return” policy may hit some serious obstacles, the most significant possibly being Iran’s own policy. According to official Iranian media releases, the U.S. walkout from the JCPOA was an illegal violation of a United Nations Security Council decision and an act of aggression against Iran. Rouhani thus expects that “the U.S. will bow to the Iranian nation.” The “bowing” will be expressed in procedure. According to Rouhani, “Iran will return to the nuclear deal within one hour of the US doing so,” thus demanding that the U.S. rejoin the deal—in other words, cancel sanctions—with no strings attached, and without a prior Iranian undertaking to roll back its violations and without IAEA verification. This version of a “super clean return” will probably meet some objections even within Biden’s administration.

Moreover, in his first speech of 2021, Khamenei demanded that “The United States … compensate Iran for the damages it has endured since President Trump withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018.” A similar demand was voiced earlier by Foreign Minister Zarif. Yet the most significant obstacle to a “clean return” may be an Iranian demand for assurances that the United States will never again leave the JCPOA.

Catherine Ashton, former E.U. foreign minister, recently revealed that the Iranians had worried even during the original negotiations over the nuclear deal about a U.S. walkout. Remember that President Obama never sent the nuclear deal to Congress. He committed the United States to join the agreement through a U.N. Security Council resolution and by lifting economic sanctions on Iran through presidential decrees. This allowed Trump to reimpose sanctions by issuing another set of presidential decrees. Consequently, Iran may demand that the United States legally bind itself to the JCPOA by an act of Congress as a precondition for “rolling back its violations.”

Zarif hinted as much immediately after the Nov. 3 elections, when he said that Iran may demand “assurances” before “it allows the US to rejoin the previous nuclear deal.” Even with its newly won parity in the Senate, the Biden administration may find it difficult to get formal congressional approval for such binding JCPOA commitments.

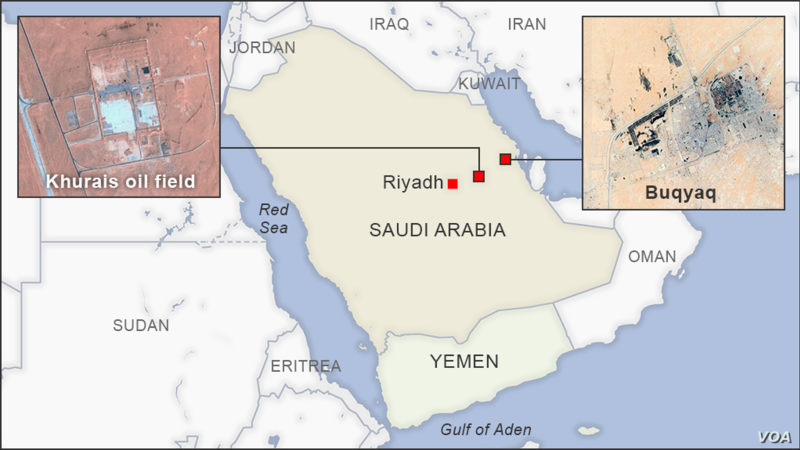

Ever since the devastating September 2019 attack by Iranian unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) on Saudi Arabia’s oil installations, the awareness has grown among many observers (including dovish analysts) that Iran’s threat to regional and global security is not limited to its nuclear ambitions. Therefore, what is needed is more than just limits on Iran’s military nuclear program, but limits on Iran’s conventional capabilities too, including its entire spectrum of destabilizing weapon programs like ballistic missiles and UAVs.

A “clean return” to the JCPOA that leaves Iran free to pursue its destabilizing non-nuclear threats may be hard to swallow for the U.S. administration and Congress, as well as in Europe. Even French President Emmanuel Macron, who in September 2019 suggested opening a $15 billion credit line for Iranian economic recovery, stipulated that first Iran would have to end its JCPOA violations, extend the duration of the agreement and enter negotiations on “regional security.” Macron’s statement anticipated Biden’s own list of Iran deal “weaknesses” by a year. In other words, a “clean return” might be objected to by some of America’s European allies.

No such objections were voiced at the Nov. 23, 2020, meeting of German, British and French foreign ministers. Reportedly, the foreign ministers did not discuss any “issues of concern” regarding Iran except the ways and means for paving America’s way to rejoining the nuclear deal. One of the suggestions made was a “super-clean return,” meaning an Iranian rollback of its violations in return for U.S. lifting of sanctions, even without the U.S. formally rejoining the JCPOA. These foreign ministers did voice concerns about prospective Iranian demands for “assurances and compensations.”

Finally, there are regional concerns to consider. Israel’s position in this matter may not count for too much in an administration eager to expunge Trump’s legacies. But the position of other U.S. allies in the region, including Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, may have greater weight in the Biden administration.

In any case, there is an obvious conflict, even a deadlock, between Biden’s minimum demand that Iran end its JCPOA violations first, and Iran’s minimum demand that the United States end sanctions first. Another conflict concerns the guiding principle of U.S. policy. Is a return to the JCPOA a “starting point for follow-on negotiations,” as per Biden, or is it the endpoint for “U.S. violation of U.N. Security Council decisions,” as per Iran?

The overwhelming majority of analysts believe that a “clean return” process is destined to be much more difficult than envisaged. It has an inbuilt deficiency, namely that the ending of sanctions strips the United States of leverage on Iran for follow-on negotiations. To work around this problem, some proposals have been floated (among others by The Economist and Financial Times) for a modified rejoining process that might be dubbed “conditional return.” This would have the Biden administration show good faith by unilaterally cancelling some of the sanctions ahead of any Iranian agreement to roll back its violations, while leaving the rest of the sanctions in place until Iran agrees to follow-on negotiations. Naturally, the two British newspapers that floated this idea also proposed that the “good faith” part of the plan be the lifting of European sanctions on trade with Iran.

Israel and the Iran nuclear deal

Was Obama’s nuclear deal beneficial or detrimental to Israel’s security? Opinions differ among Israeli analysts and leaders. One school of thought is that the sole existential threat to Israel is a nuclear Iran, hence the deal improved Israel’s security. This is the view of Haaretz editors who have argued that “The Iran nuclear deal lifted the single existential threat on Israel, since only nuclear weapons constitute such an existential threat.” This view is apparently shared by the IDF High Command, as reflected in a recent statement by Lt. Gen. (res.) Gad Eizenkot, former IDF chief of staff. He wrote that “Iran is not an existential threat to Israel,” referring to a non-nuclear Iran.

Another (apparently minority) school of thought believes that Israel is facing an existential threat not only from Iran’s nuclear-weapons program but from its conventional weapons build-up, too. Recent technological advances render small, densely populated nations like Israel susceptible to nuclear-scale “unacceptable damage” from precise conventional weapons. Indeed, the intentional exclusion of missiles from Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran was perceived by those in this latter school (and by others) as a “green light” for Iran’s ballistic and cruise missile programs and their aggressive use across the Middle East.

Seen from this perspective, Obama’s nuclear deal did not reduce the existential threat to Israel, but rather shifted its main thrust. Since Iran’s nuclear and non-nuclear threats are connected, U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal (while motivating Iran to resume its drive towards nuclearization) diminished Iran’s capacity to enhance its threatening non-nuclear capabilities. Unless the “weaknesses” of the original nuclear deal are corrected, Biden’s return to the deal will not improve Israel’s security but rather shift the thrust of the Iranian threat to Israel from the nuclear to the non-nuclear domain.

Still, even those Israelis who see a nuclear Iran as the sole existential threat hope for a revised deal that will correct the “weaknesses” pointed out in Biden’s September 2020 statement. By way of example, it is important to understand how just one of those “weaknesses”—the ignoring of Iran’s ballistic and cruise missile programs, including drones and UAVs—greatly threatens Israel.

Indeed, there is a fundamental gap in perception of the Iranian threat that places Israel and other Middle Eastern states on one side of the argument, and the United States and Europe on the other. For the latter, the only prospective threat from Iran is a future nuclear arsenal capable of hitting European and U.S. targets. For this threat to materialize, the Iranians need both nuclear weapons and long-range missiles to deliver them. Since Iran’s conventional missiles have not been perceived as threats, the architects of Obama’s nuclear deal did not see any need to put any limitations on them. For Israel, Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states, the Iranian threat is far more complex, consisting of three components: The threat from nuclear missiles, the threat from non-nuclear missiles and the threat from missiles in the hands of Iran’s proxies. From Israel’s perspective, Obama’s nuclear deal reduced potential threats to Europe and the United States at the cost of increasing the Iranian threat to Israel and the Gulf states.

Israel has never objected to an agreement that would stop Iran’s military nuclear program. Rather, it has objected to the specific agreement crafted by the Obama administration, which Israel’s prime minister called “a bad deal.” One of Israel’s main objections was to the exclusion of Iran’s missiles—most of which are nuclear-capable—from the deal, as well as the deal’s complete disregard of Iranian transference of missiles and technologies to its regional proxies. A “clean return,” even if accompanied by vague promises for “further negotiations,” will practically stamp a seal of approval on Iran’s missile programs and regional belligerency. It stands to reason that Israel will voice its reservations about this to the Biden administration.

How will the new U.S. administration react to Israel’s reservations? As noted above, the Biden administration is robustly motivated towards a “clean return.” Its motivations derive from ideological and pragmatic considerations, but also from the fact that many senior Biden administration officials were directly involved in negotiating the Obama nuclear deal; they have a personal stake in its revival. The desire to expunge Trump’s key policies from the U.S. ledger also will play a major role in future policy.

If the “clean return” process proceeds smoothly—and this depends to a large degree on Iran’s response—it is reasonable to assume that Israel’s objections will be politely rebuffed. At most, Israel will receive some “compensation,” perhaps in the form of U.S.-led regional diplomatic initiatives. If, on the other hand, the “clean return” process hits the anticipated obstacles, the administration may move to a policy of “conditioned return.” If the “sweetener” of lifting some sanctions is symbolic rather than substantial, Biden will still retain leverage to demand follow-on negotiations. In such a situation, the administration might be better attuned to the concern of its Middle Eastern allies—their insistence on curbs not only for Iran’s nuclear programs but also its missile programs.

The limitations Israel and other Middle Eastern countries wish to impose in Iran’s missiles are of two kinds: general and range-related. In the first category, Israel and Saudi Arabia may demand the limitation of missile and technology transfer from Iran to its proxies. Another request may be the revision of the single paragraph in the Obama nuclear deal that relates to missiles. This paragraph calls for Iran to refrain from developing and testing “missiles designed to be capable of carrying nuclear warheads.” In other words, the agreement mentions only such missiles that are specifically designed to carry nuclear warheads.

Each time the West has protested over Iranian ballistic missile and space-launch tests, the Iranians respond with two defenses. First, that the nuclear deal “calls to refrain” rather than “forbids” Iran from developing and testing missiles. Second, that the tested missiles are not specifically or deliberately designed to carry nuclear warheads. The Iranian response is formally accurate. In fact, the wording of the Obama agreement permits the Iranians to develop ICBMs, as long as they are not deliberately designed to carry nuclear warheads. The ambiguous language was not accidental, but rather a sophisticated ruse employed by U.S. negotiators to waive Iran’s missiles out of the deal without appearing to do so to non-expert readers.

It will be reasonable for Israel to request the phrasing to be simplified and tightened to “missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads,” dropping the words “designed to be.” The internationally accepted norm for a nuclear-capable missile is a payload of 500 kg. and above, regardless of what that payload is. Most of Iran’s ballistic and cruise missiles fall into this category.

As for range limitations, it stands to reason that this will be quite controversial. The United States is about 7,000 kilometers away from the nearest point in Iran. The distance between Iran’s western border and the nearest European Union member (Bulgaria) is 1,450 kilometers. The Iranian leadership has announced a self-imposed limitation of 2,000 kilometers on the range of all their missiles, whether ballistic or cruise. The European Union has never protested this, although it puts some E.U. territory in Bulgaria, Greece and Romania within Iran’s missile range.

In a discussion of this issue with Israeli analysts, former senior officials of the Obama administration have voiced their opinion that the range limitations on Iran’s missiles should be 2,000 kilometers “because the Iranians will never agree to anything else.” It seems likely that this will be the position of the Biden administration.

If formalized in a new nuclear agreement, this range limitation will put an international seal of approval on all Iranian missiles with ranges below 2,000 kilometers. In other words, acceptance of all Iranian missiles that threaten Israel and the Gulf states. From Israel’s perspective, it is better not to specify any range limitation rather than specify a limitation that enhances the security of Europe and the United States at the cost of reducing Israel’s security.

Israel would do well to coordinate its position on Iran’s missile-range limitations with Saudi Arabia and Gulf states, even if in the end this position is rebuffed by the Biden administration. Such coordination will build additional confidence between Israel and other Middle Eastern countries threatened by Iran’s missiles.

Conclusion

A U.S. return to the Iran nuclear deal will decisively shape the future of the Middle East and Israel’s security environment, for better or worse. A “clean return” is apt to diminish U.S. clout and destabilize the Middle East. If the U.S. administration “bows to the Iranian nation” by rushing back into the Obama nuclear deal with no substantial correction of its “weaknesses,” the ayatollahs will justifiably regard this as a historic victory. Iranian prestige and standing in the region will be enhanced immensely, and Iranian coffers will overflow with income from oil exports and the renewal of international trade.

Iran after a “clean return” will be stronger and more dangerous, posing a growing existential threat to Israel and other Middle Eastern countries—even if its nuclear program is delayed. It is reasonable to assume that a “clean return” that amounts to an Iranian victory also will discourage Arab states from further normalizing relations with Israel.

If, on the other hand, the Biden administration negotiates a revised nuclear deal that fixes the obvious weaknesses of the JCPOA; if the duration of nuclear limitations is extended; if Iran’s missile programs are restricted; and if its missile transfers to its proxies are ended—the Middle East will become significantly more stable. The security of Israel and the Gulf states will be enhanced. This will allow the United States to further disengage from the Middle East with lower prospects of being drawn back in (as happened following the rise of the Islamic State). Only a “conditioned return” that does not leave Iran as a regional hegemon may improve global security.

Uzi Rubin was the founding director of the Israel Missile Defense Organization, which managed the Arrow program. He subsequently served as Senior Director for Proliferation and Technology in the National Security Council (1999-2001), and directed several defense programs at the Israel Aerospace Industries and in the Defense Ministry. He was twice awarded the Israel Defense Prize (1996 and 2003), and was also awarded the U.S. Missile Defense Agency “David Israel” Prize (2000). He has been a visiting scholar at the Stanford Center for International Security and Arms Control, where he directed a study on missile proliferation.

This article was first published by the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security.