Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People is soon to be released in theaters around the country, starting with March premieres in New York City and Los Angeles.

The 85-minute documentary traces Pulitzer’s life as a Jewish immigrant from Hungary to his rise as the powerful publisher of both the St. Louis Post-Dispatchand the New York World. It capsulizes some of his famous campaigns, his innovations in the art of newspapering, and his battles with such luminaries as William Randolph Hearst and Theodore Roosevelt.

Directed by Oren Rudarsky, the documentary skillfully weaves together historic photos, voice reenactments, and newspaper front pages and headlines with interviews of 13 experts on the publisher. Among them were his descendant Emily Pulitzer and Hasia Diner, one of the nation’s foremost historians of the Jewish experience in the United States.

Pulitzer came to the United States in 1864 as a recruit for the Union Army in the American Civil War. He taught himself English by reading the works of British novelist Charles Dickens. After the war, he headed west from New York City, supporting himself with a series of such jobs as shoveling coal on a barge, burying victims of cholera, and clerking in an immigration office. An excellent chess player, he once kibbitzed as he watched former Union General Carl Schurz play chess at the Mercantile Library in St. Louis. Impressed, Schurz, a future U.S. senator from Missouri, took him under his wing.

Pulitzer went to work for a German-language newspaper in St. Louis, and as a joke, a civic group nominated him to run for the state Legislature. To their surprise, he won. Impressed that someone so recently an immigrant could be elected to make the state’s laws, Pulitzer ever after was a champion of democracy. He later served as a police commissioner in St. Louis before purchasing the Dispatch, which he merged with the Post to create the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Almost immediately, Pulitzer recognized that to be successful, a newspaper had to be willing to make enemies. That he did, by publishing the names and incomes of people who paid no taxes, identifying them as “tax dodgers” in his headline. He married Kate Davis, an Episcopalian, who was a distant cousin of the former president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis. Admitted to Episcopalian society, Pulitzer celebrated by taking his wife on an extended European tour for their honeymoon.

While maintaining ownership of the Post-Dispatch (which would stay in his family for three generations until 2005), Pulitzer moved to New York where he purchased the New York World, paying $400,000 for the paper. His brother Albert had preceded him to New York, where he too published a newspaper, The New York Journal. Albert turned down Joseph’s entreaty that they merge their two papers, prompting Joseph to stage a raid, hiring away three of Albert’s most important staff members. Years later, when William Randolph Hearst purchased the Journal, he did the same thing to Joseph Pulitzer, hiring his writers, editors, illustrators, and cartoonists.

Pulitzer’s arrival in New York City came at a fortunate time when the city had become so large that people had to commute to work, occasioning in their schedule time to read a newspaper. Pulitzer championed working men and women, even supporting their unions – except for those unions that wanted to organize at his newspaper.

He urged his reporters to dig up stories about life in New York, not only about the politicians, but also about common, every day people, admonishing the reporters to “never lack sympathy for the poor.”

Almost immediately after arriving in New York, he campaigned for the Brooklyn Bridge to be free for pedestrians, urging city officials to remove the 1-cent pedestrian toll. “A penny is a working man’s lunch,” he thundered.

His next big campaign was to pay for the pedestal on which the Statue of Liberty sits in New York Harbor. France had donated the statue without a pedestal, and when the government turned a deaf ear for pleas that it be mounted appropriately, Pulitzer asked his readers to donate their pennies and dimes to build the pedestal. One hundred twenty thousand people donated to the fund.

Nellie Bly applied for a job as a reporter and was told by the World she could have one if she came up with a scoop. Feigning insanity, she got herself admitted to the government-run insane asylum, and later wrote of the horrific conditions there, prompting successful demands for reform.

At one point, Pulitzer got himself elected to Congress, but resigned early in his term, realizing that he could wield far more power as the publisher of a large newspaper.

The World not only published stories about the working class, but also doled out advice for immigrants, explaining to them how the American political and economic systems worked. It also published dress patterns, sheet music, and even cut outs that could make reading the newspaper a three-dimensional affair.

One cartoon that ran in his newspaper was called “Hogan’s Alley.” In the multi-charactered scenes was always one vagabond little boy wearing a yellow coat. Soon people asked others if they had seen the latest installment featuring the Yellow Kid. After Hearst stole away cartoonist Richard F. Outcault, and his newspaper began featuring the same character, the “yellow kid” became symbolic of the type of sensationalism both newspapers engaged in. Thus was born the term “yellow journalism.”

New York’s high society was generally hostile to Pulitzer’s coverage of the poorer residents of New York City, with one latter-day commentator suggesting “by covering the disenfranchised, Pulitzer empowered them.” He also built up a tremendous circulation, bringing the number of copies sold per day from 15,000 to over 400,000.

Among Pulitzer’s biggest advertisers were department stores, which grew along with the newspaper industry. So too did newspaper coverage help expand the reach of the entertainment and sports industries, as well as the stock market.

Flushed with success, Pulitzer built a towering building with a gold dome for his newspaper, which could be seen from 40 miles away. It was said that the first two structures immigrants saw sailing into New York were both Pulitzer influenced projects: The Statue of Liberty and the New York World building.

However the sights that greeted immigrants soon were denied to Pulitzer. He went blind, and also developed extreme sensitivity to noise. He sound-proofed his homes and his yacht to protect himself against stray noise. But music was one sound that he continued to love: he kept up his attendance at concerts.

He became ever-more demanding as a result of his disabilities, prompting his wife to complain at one point that there was “not a servant in the house who worked harder than I have.” She added that she felt like a slave.

In the head to head battle with Hearst, Pulitzer paid for reporter Nellie Bly to travel around the world, sending dispatches along the way.

The two newspapers competed with each other over which could beat the drum louder for a war with Spain following the sinking of the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana harbor. The World’s circulation hit 820,000 copies per day, with between five and seven editions rolling off the press.

However, after the war, Pulitzer regretted that the United States had become a colonial power, winning from Spain not only Cuba, but also such far-flung possessions as Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. Pulitzer argued that as a colonial power America’s attention was diverted from providing for its own citizens health, education and welfare.

Pulitzer’s battle with Theodore Roosevelt came after the United States fanned a revolution in northern Columbia, which eventually resulted in the creation of the new nation of Panama, which immediately negotiated with the United States the right to build a canal.

The newspaper publisher charged that there was considerable corruption in the building of the canal, suggesting that as much as $40 million was pocketed by corrupt agents. Roosevelt, who considered the canal his greatest achievement, was furious with Pulitzer, and urged his attorney general to file a “criminal libel” suit against Pulitzer – a class of libel then unknown.

In 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously sided with Pulitzer on grounds that the U.S. Constitution had guaranteed freedom of the press. While the victory was sweet, Pulitzer could not savor it for very long. Within less than a year, he died aboard his yacht.

In Pulitzer’s will, he set aside money for the creation of a school of Journalism at Columbia University and for the awarding of a Pulitzer Prize.

He was a giant in journalism and a mighty friend of the working classes.

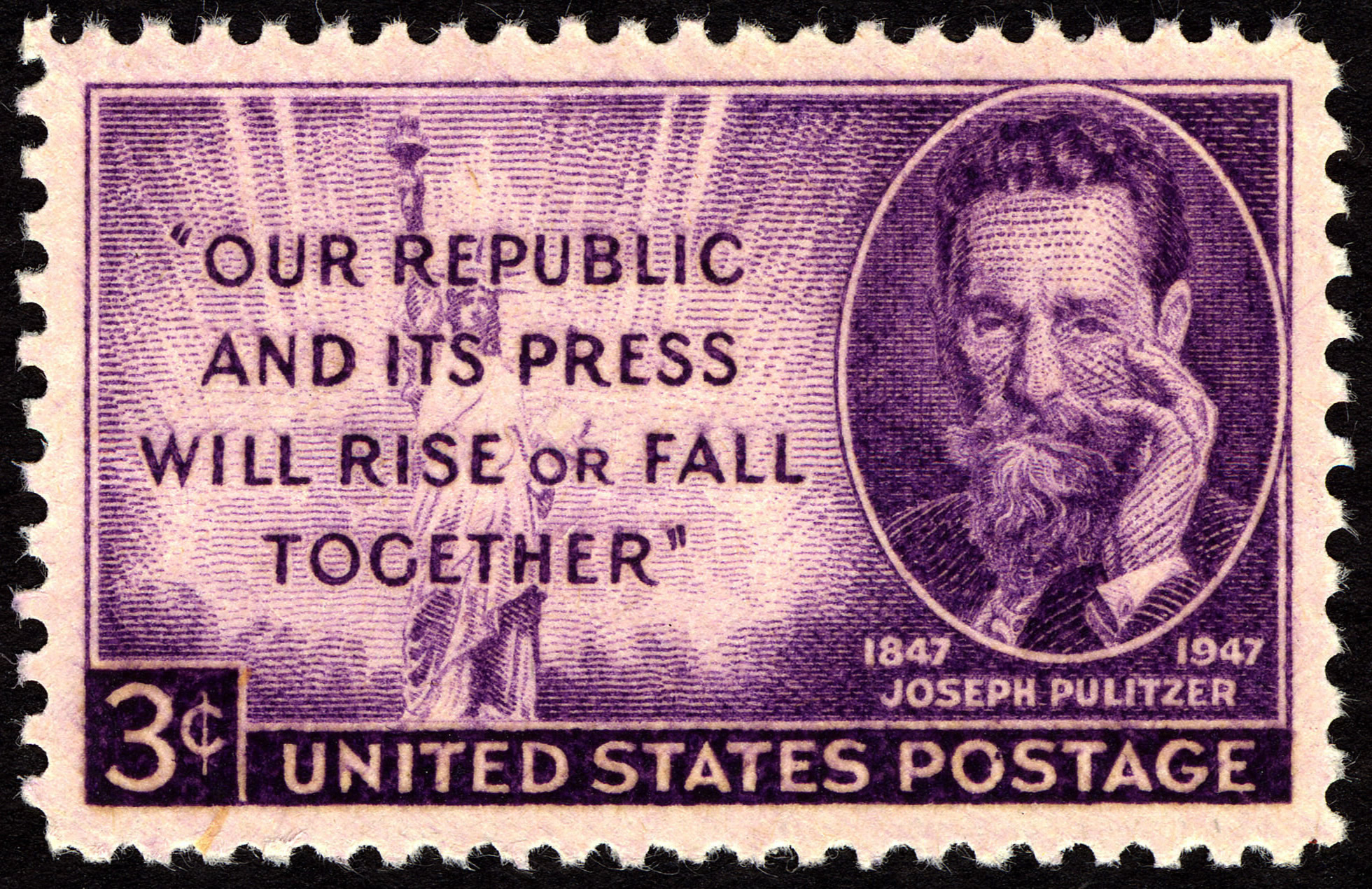

Joseph Pulitzer