Toward the end of his life, I heard Isaac Bashevis Singer give a reading to a packed auditorium at MIT. Afterward, a member of the audience rose to ask a question. “Please, Mr. Singer, say something in Yiddish!”

“Nu,” said Singer. “What should I say?”

“Anything!” the woman said. “We just want to hear someone speak to us in Yiddish.”

For this woman, the mere sound of Yiddish evoked a world as distant and mystical as Middle Earth. The wizened, bald author might as well have been a native speaker of Elvish.

Never mind that thousands of Hasidim still carry out their daily lives in Yiddish. Or that the world in which our ancestors lived was rarely if ever mystical. The closest most Americans today will come to Yiddish literature is Fiddler on the Roof, a simpler, sweeter version of Sholem Aleichem’s far darker and more disturbing tales. (Have you ever heard about Shprintze, the daughter Tevye pimps out to a rich young man, who uses her for sex then refuses to marry her? Shprintze tries to tell her father how unhappy his scheme has left her; when he won’t listen, she drowns herself in the river. Funny, Shprintze never made it to Broadway.

Having read (in translation) most of Sholem Aleichem’s oeuvre, along with both Singers’ (Isaac Bashevis and Israel Joshua), and Chaim Grade’s, I fully expected that when I picked up the new anthology Have I Got a Story for You: More than a Century of Fiction from the Forward, I would discover at least a few gems. After all, the editor, Ezra Glinter, combed through 120 years’ of the archives of the foremost Yiddish-language newspaper in America to ferret out the strongest fiction. Even so, I was stunned by the unrelentingly high quality of all these stories. And who could have predicted that nearly half the authors would turn out to be female? If any up-and-coming literary scholars are searching for unjustly ignored feminist writers, yoo-hoo, here they are! All on its own, the table of contents of this anthology could provide the inspiration for eleven dissertations.

Again and again, the authors included in Glinter’s book remind us that writing in Yiddish was a radical act. Whether in Europe or America, Yiddishists were thumbing their noses at an establishment that decreed that high-class literature could be penned only in “real” languages—Russian, German, French, maybe even Hebrew—but never in a jargon of the streets, an earthy and profane grandmothers’ tongue like Yiddish. For an educated Jew in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, writing a serious story in Yiddish was often a statement of ethnic pride, like an African-American writer of the Harlem Renaissance choosing to write in black urban dialect, or a composer today writing a musical about our nation’s founding fathers in rap.

Not only do the stories in this anthology resist sentimentality, most are harrowing in their realism. Given the authors’ socialist politics, it isn’t surprising that they portrayed their characters as torn by conflicts engendered by the larger social, political, or economic forces that surrounded them. Yet the focus remains on the individual. And the authors—thank God—leave their readers mulling complex questions rather than trying to browbeat them with didactic answers. (Strangely, the only story that suffers from heavy-handedness is Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “The Hotel” [trans. Ezra Glinter], which strikes me as that author’s weakest work.)

The stories in this anthology tend to be so hard-hitting that the folksy title, Have I Got a Story for You, clever as it may be, eventually strikes a misleading tone. The same might be said for the title of the first entry, “Golde’s Lament” (trans. Myra Mniewski), which leads a reader to expect a Jewish mother oy-veying her way through a complaint about an ungrateful daughter or her burdensome list of chores. Instead, the story is a compelling psychological study of a woman whose husband is due to depart the next day for America … without her or their children. Instead, the man will be traveling as the “husband” of a woman whose real spouse has already emigrated. The reasons for this ruse, bureaucratic and financial, are not entirely convincing. Is something going on between the wealthier woman and the protagonist’s husband? Or is the left-behind wife giving in to paranoia?

Published in 1907, “Golde’s Lament” is as beautifully crafted as a story one might find in this week’s New Yorker. Yet I had never heard of the author, Rokhl Brokhes. Why? Because she was a woman? Because she wrote in Yiddish? Because she was a Jew? Because the eight-volume edition of her work that was due to be published in the early 1940s was consigned to oblivion by the German invasion of the Soviet Union? Because Brokhes herself was consigned to die in the Minsk ghetto during the war that followed? Because all of the above?

The torture Golde suffers should be familiar to anyone who has ever been in love. But Golde’s jealousy might never have found an opening to infect her if the protective shell surrounding her domestic life hadn’t been shattered by immigration. With Jews uprooting themselves from the world in which their roles had been fixed for so many centuries, hurrying to a land beyond the sea where no one knew them, they suddenly seemed free to reinvent themselves as whatever they were creative or chutzpadik enough to imagine they might become. “Modernity can be seen as the subject of nearly all of modern Yiddish literature,” Glinter writes (p. 81). In the years immediately before, during, and after World War One, Jewish authors confronted not only immigration to the New World, but also “the rise of Jewish socialism and the labor movement, the entry of Jews into higher education and the professions; a swiftly changing relationship to traditional Judaism; the challenge of Zionism; and new and different forms of both emancipation and anti-Semitism” (p. 81). As Glinter repeatedly reminds us, nearly every writer in this collection—at least the men— underwent a traditional Jewish education before breaking away to a more secular life. If the work here strikes us as oddly contemporary, that may be because nearly every contemporary story or novel written by an American who isn’t straight, white, male, and middle class explores similar questions of identity.

Nor were Yiddish authors shy about examining the ways in which romantic and sexual mores were changing, especially as applied to women. Far from being viewed as tokens, Glinter notes, “Female authors were so prized that the Forward took pains to highlight the gender of its contributors” (p. 82).

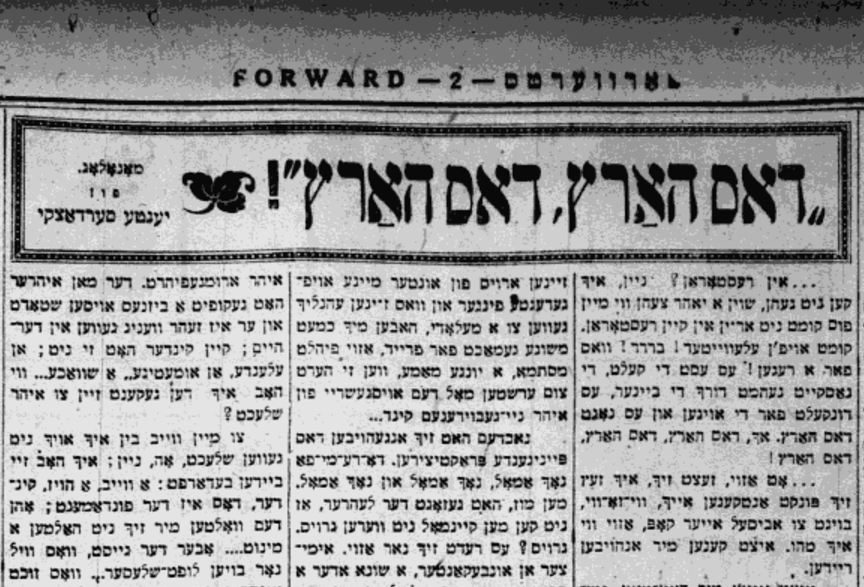

Take Yente Serdatsky. Born in 1877, Serdatsky was apprenticed to a seamstress at thirteen, yet she still found the time to tutor herself in German, Hebrew, and Russian literature. After the Revolution of 1905, she deserted her husband and children and moved to Warsaw, then to the United States, where she ran a soup kitchen and published stories about young women trying to live their lives to the fullest, or, at the least, maintain their independence. In one of the three stories by Serdatsky included in this volume, a young widow struggles to decide whether to have an affair with a married union organizer who, conveniently for him, believes in free love.11

“His love for other women was the holiday of his life,” the narrator explains, “the inspiration behind his daring work for the sake of the masses.” Sleep with me, he promises the young widow, and you will enter a world in which free, intelligent women become artists, earn a lot of money, attend the opera, and “spend time in cafés having intellectual conversations with knowledgeable men who relate to them as they would to close friends. …” Even those who are not as beautiful as she is, he says, “wield power in affairs of love” (p. 129). Is the union organizer offering the widow a way to free herself from convention and relieve her agonizing loneliness? Or is he feeding her a self-serving line? We’re never quite sure, and neither is the widow. Should she give in and sleep with this man? Shouldn’t she? As I read Serdatsky’s story, I couldn’t help but think that Grace Paley (she of blessed memory) didn’t show up out of nowhere. Even as Paley was growing up, feisty feminists like Yente Serdatsky were making a case for the literary importance of urban Jewish women’s lives and loves.

Or consider Lyala Kaufman, who is usually relegated to her role as the daughter of Sholem Aleichem and the mother of Bel Kaufman, one of the first bestselling American female Jewish authors. Who knew that after publishing a remembrance of her father in the Forward, Lyala went on to pen more than 2,000 sketches of Jewish American life. Virtually none of which have been translated or collected. Are they masterpieces? No. Are they emotionally and psychologically complex glimpses of what it meant to be a Jew in the first half of the twentieth century? You bet they are.22

At least I had heard of Lyala Kaufman. Miriam Raskin was entirely news to me. Born in 1889 in Belarus, Raskin joined the Jewish Labor Bund, participated in the Revolution of 1905, survived a year in prison, and made it to the United States. Here, she published stories such as “She Wants to Be Different” (trans. Laura Yaros), the portrait of strong-willed Eva, who delights in the independence she has achieved as the owner of her own beauty salon. Although she is willing to be escorted to social events by her chubby, shlubby boyfriend, Novick, Eva isn’t about to marry him, having already fled a husband who wanted to bend her to his will. After all, Eva thinks herself superior to other women, entertaining a persistent (if vague) hope that something extraordinarily will still happen to her. Are we meant to admire Eva for her bravery? If so, then why do we suspect she is overly impressed with her superiority, that she is overlooking Novick’s finer qualities and consigning herself to a life of loneliness? Happily for the reader (if less happily for Eva), the answer remains ambiguous.

While the authors in this anthology aren’t timid in criticizing the sexism that constricts the lives of their female protagonists, they also don’t hesitate to portray genuine love between the sexes. (One of the authors, Sholem Asch, is famous for having written a play involving a lesbian affair between a prostitute and the daughter of a brothel owner.33 Sadly, none of the stories in this collection go so far as to take on homosexual love.) In “Friends” by Hersh Dovid Nomberg (trans. Seymour Levitan), a man who has found marital bliss invites his best friend, a bohemian poet, to dinner. So effective is his attempt to convince this friend of the benefits of bourgeoisie married life that the man takes to hanging around at all hours, showing his appreciation of the businessman’s wife. When the woman dies, her husband nearly loses his mind from grief.

He fell into a hard, heavy sleep, but suddenly woke, as if from something awful, and suddenly he seized his head and began howling between the four walls and the empty bed that heard him. How did this happen? When did it happen? How? …

This is death, death, he said to himself, as if he just now properly comprehended the import of the short word. That’s what it is—death. (p. 91)

Gradually, the widower comes to realize that his friend is almost as riven by grief as he is. All doubt fades: the friend and the wife truly were in love. The question becomes whether it comforts the man to have company in his mourning, or whether his joy in his marriage has been ruined.

Even when the stories in this anthology leave the domestic sphere for the wider world of war, the focus remains on the individual. In ways that American readers wouldn’t fully appreciate until the appearance of novels by Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer, and Joseph Heller, authors like Sholem Asch and David Bergelson portrayed battlefields devoid of glory.

“For decades the factories had been manufacturing weapons,” the narrator of Asch’s “The Jewish Soldier” (trans. Saul Noam Zaritt) informs us. “ … Great wise men sat sequestered away in rooms where they deliberated day and night on how to make bigger weapons and bigger bombs, which would be filled with even more terrible things that could bring about more annihilation” (p. 176). A paragraph later, the narrator paints a picture of the cavalrymen who will soon suffer the annihilation these great machers have planned, scores of soldiers “all of different nationalities and lands—Russians, Ruthenians, Lithuanians, Poles, Jews. All looked the same now, in the same gray, earthen uniforms and each with a rifle in his hand and a knapsack on his back.”

Finally, among these thousands of men, the author narrows his focus to just one soldier, “the Jew Asnat,” a young intellectual who has, against all good sense, signed up for the Russian army, perhaps to prove that he is as patriotic as his gentile countrymen, or because he longs to claim a homeland, or for no reason at all. A full year after he has joined the army, Asnat is no wiser about his motives than he was before. Should Jews fight for a country that denies them their humanity? Should they attempt to prove they are as brave and patriotic as their fellow citizens? Or should they say to hell with Mother Russia and flee, hide, fight for the other side? One minute, the gentile soldiers are abusing a Jewish comrade, holding him down and stuffing pork in his mouth. The next, as death approaches, the men literally kiss and make up and swear allegiance to each other’s gods. Accustomed as we are to hearing about our male ancestors fleeing conscription in the Tsar’s army, these stories of Jews who actually signed up and fought are a revelation.

Although “The Jewish Soldier” can’t help but remind readers of the stories of Isaac Babel, the more dominant influence throughout Glinter’s anthology seems to be Anton Chekhov. If anything dates these stories, it is their straightforward, unabashed, Chekhovian rendition of human suffering, their lack of irony in conveying the full range of human emotion, their authors’ refusal to judge their characters. And yet, for these very reasons, the stories consistently come across as daring and fresh.

Finally, the last few entries in this anthology prove that even in the twenty-first century, Yiddish literature can still speak to young Americans. Blume Lempel, who died in 1999, contributes an erotic feminist folktale that might have come from the pen of Angela Carter or Leslie Marmon Silko. With its wildly poetic magical realism, “A Journey Back in Time” (trans. Ellen Cassedy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub) describes a woman’s capture by a woodsman who picks her up and throws her over his shoulder “as if I were a wild animal he’d shot and killed.” Back in his cabin, the man’s shadow assumes the shape of a billy goat, or “a pagan god with singed wings” (p. 388). His tongue slowly draws lines on the woman’s brow. And all the while, Barbra Streisand croons seductively from the gramophone.

The complexity of the decision of contemporary authors such as Mikhoel Felsenbaum and Boris Sandler (the most recent editor of the Yiddish Forward) to write fiction in Yiddish deserves more discussion than Glinter provides. Oddly, in their familiarity, these last few stories in the anthology seem less groundbreaking than their predecessors. The shleppy anti-hero of Felsenbaum’s “Hallo” (trans. Eitan Kensky) could have stepped from a comic novel by Gary Shteyngart (not surprising, perhaps, given that both authors grew up in the Soviet Union), while the sexually precocious narrator of Sandler’s “Studies in Solfège” (trans. Barnett Zumoff) could have issued from the laptop of any one of an army of young Jewish males happily composing their memoirs this very day in Brooklyn. And yet, the reader can’t help but marvel that a language so easily dismissed as quaint can so easily be adapted to meet the demands of life in the twenty-first century.

If you want to take a trip down nostalgia lane, I will mail you a ticket to the current Broadway revival of Fiddler (even if this one closes, I’m sure there will be another revival soon). But if your system is averse to schmaltz and you want to gain more complicated insights into what it was really like to be a Jew in Europe and America for the past hundred and twenty years, then I advise you to go out and buy a copy of this new anthology.