The varying experiences of desperate European Jews who made their way to Canada between 1933 and 1955 are highlighted in a new online resource produced by the Montreal Holocaust Museum (MHM).

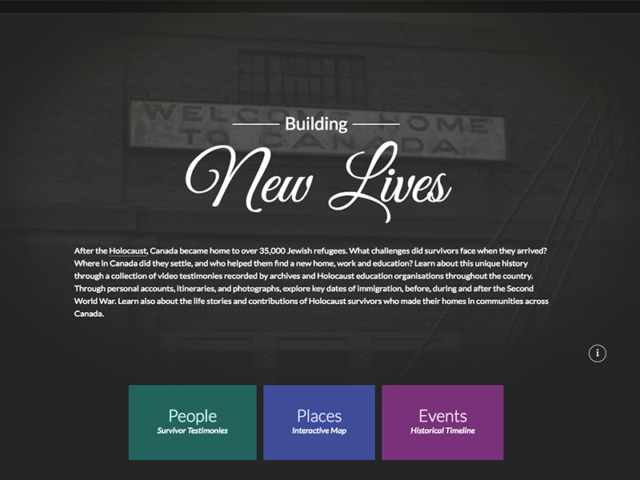

Building New Lives is a “virtual exhibit” that reminds viewers that over 35,000 Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution came to this country during that period, the great majority of whom arrived after the war.

Despite the hardships they faced in getting here, and the indifference and hostility they often met from Canadians, the exhibit’s message is that these refugees did well for themselves and for the country.

MHM executive director Alice Herscovitch said the project is different from the museum’s other educational resources, in that it focusses on how Jews managed to flee Europe before, during and after the war, and the challenges all of them faced as immigrants to Canada.

Through their videotaped testimonies – as well as maps, historical context and a raft of photos – these individuals’ journeys are brought to life. Building New Lives also explores Canada’s response to the Jewish refugee crisis and the evolution of immigration policy.

“Our hope is that today’s refugees will see that it’s not easy, that it takes time, but it is possible to make a real contribution to this country. We hope all Canadians will learn we have a responsibility toward today’s refugees,” Herscovitch said at a launch event for the new website on March 14.

Building New Lives, which is funded by the Virtual Museum of Canada, has been under development for three years.

Available in English and French, the content was gathered from archives across the country. Besides the MHM, contributors include the Sarah and Chaim Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre in Toronto, the Ontario Jewish Archives, the Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada and the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. Several universities and other institutions, as well as some living survivors, lent material and expertise to the project, as well.

The stories are wide ranging. Gerhart Maass got out of Germany in 1938 and landed in Depression-era Montreal when he was 19. He recalls that Jews shunned him for years because they felt the German Jews had not done enough to help the Jews of eastern Europe. At the same time, he remembers signs in the Laurentians saying, “No dogs or Jews allowed.”

“The sense I did not belong anywhere was a frightening, traumatic experience,” he said.

Then there is Elliott Zuckier. Born in Poland in 1928, he survived the ghetto, slave labour, Auschwitz and a death march. He languished in a displaced persons camp before he was lucky enough to be among the 1,200 youths who were brought to Canada as war orphans in 1947, under the joint sponsorship of the Canadian government and the Jewish community. He was billeted with a Jewish family in Calgary, where he spent the rest of his life.

Sarah Engelhard, one of the few Jews who were let in during the war, attended the launch. “It’s a miracle I’m here,” she said.

Her family lived in Toulouse, France, under false identities until 1942. When their was cover blown, they fled over the Pyrenees on foot (her brother was just a toddler) to Spain and hid in Barcelona for two years.

In 1944, when Engelhard was 12, they were among 450 refugees in the Iberian Peninsula who were granted visas to Canada and voyaged aboard the fabled Serpa Pinto to Philadelphia. Armed guards prevented them from touching American soil before they were hustled onto a sealed train to Montreal.

Maps illustrate the survivors’ routes to freedom, often through several locations in Europe, and where they ended up settling in Canada.

There’s also a timeline containing three periods – 1933-1939, 1939-1945 and 1945-2000 – which track the major events in Europe and Canada that affected the fate of Jewish people.

Adara Goldberg, a historian who narrates this section, is the author of the 2015 book, Holocaust Survivors in Canada: Exclusion, Inclusion, Transformation, 1947-1955, and a post-doctoral fellow in Holocaust and genocide studies at Stockton University in New Jersey.

During the Nazi era, Canada admitted only about 5,000 Jewish refugees, less than any other Western country, she noted.

Canadian Jews wanted to save European Jewry, but integrating them into their own communities was another matter.

– Adara Goldberg

Goldberg acknowledged that the Jewish community was not always welcoming, either.

“Canadian Jews wanted to save European Jewry, but integrating them into their own communities was another matter. That meant listening to their stories, and about those who did not survive. There was a great disconnect in experience,” she said.

Herscovitch does not agree that it is getting harder to talk about the Holocaust, or that “people are tired of hearing about it,” as one audience member regretfully put it.

“There is more, not less, interest in the Holocaust today. People want to learn about it and reflect on what’s going on in the world today,” said Herscovitch.

“There were 68,000 downloads of our pedagogical material last year.”