The biography of Julius Rosenwald, one of the most thoughtful and transformative philanthropists in American history, parallels the life experiences of many Jewish immigrant families of the mid-19th century—women and men who left German-speaking lands, relied heavily on family and community networks, and arrived in America with commercial skills that served them well.

Enjoying the benefits of whiteness, they arrived just in time for the physical expansion of the United States across the continent, referred to by patriotic orators as “Manifest Destiny.” Americans who moved west desired consumer goods to make life comfortable. Jews, as peddlers or settled merchants, followed these farmers, miners, loggers, and other pioneers, selling them clothing, shoes, household goods, and other personal and domestic items.

Many Jewish Americans thrived; Rosenwald’s success was monumental. As the genius behind the expansion of Sears, he became the 57th-wealthiest person in U.S. history, according to one recent estimate. Still, he identified with his fellows, consistently remarking how, as a Jew, he owed so much to America, which had played such an important part in making his luck possible.

Rosenwald gave away his riches as a new American, grateful to his country, but also as a Jew: The inheritor of a tradition that emphasized individuals’ responsibilities to their communities. Despite his own vast wealth, Rosenwald believed that an America without great gaps between rich and poor, and without sharp divides based on religion and race, would be a better place to live—safer for Jews, and for others. His charitable works reflected his conviction.

Rosenwald did not like the words “philanthropy” or “charity”—his approach to giving was informed, instead, by the world of consumer commerce. As a businessman, he believed he had a responsibility to provide goods to people who wanted them, and that consumption was a unifying force. A nation that consumes together, he would say, could find ways to stay and live together. Rosenwald’s idea of the civic good held that no one should be so poor, so disinherited, and so alienated as not to be able to afford or want cutlery, dishes, wallpapers, new dresses, and beyond.

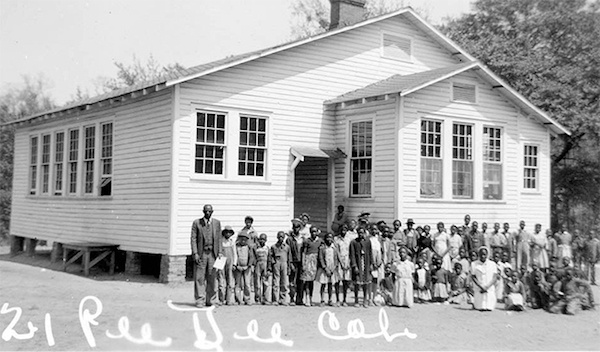

The Pee Dee Rosenwald School, in Marion County, South Carolina, c. 1935. Photo courtesy of South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

Of course, a constantly expanding population of American consumers—spanning otherwise profound divides of class, geography, and race—had helped make his fortune. Rosenwald, known to his friends as JR, grew up comfortably, but only that. His father, a German-Jewish immigrant, started out in America selling small goods house to house, a pack on his back, but eventually became the owner of a modestly successful men’s clothing store in Springfield, Illinois. JR, who was born in 1862 and grew up behind the cash register of his father’s store, aspired as a young man to make his mark in the world of business. He was struggling as a manufacturer and salesman of men’s summer suits when he got an opportunity to invest in Sears, Roebuck—a relatively new, but already successful, mail order operation specializing in the sale of watches. Buying in seemed like a good idea, but JR did not have the cash. He turned to relatives to loan him the money.

It was a fortuitous move. Rosenwald, who had a keen read on consumers, went on to oversee a colossal transformation at Sears, turning it into one of the nation’s largest retailers and becoming a very rich man in the process. He figured out how to sell to all Americans—rural, urban, and suburban; poor and well-off; immigrant and native-born—delivering a dazzling array of stuff they wanted (or learned to want through Sears’s wish book, the fabulously popular catalog). A shopper could buy almost anything from Sears, except for firearms and patent medicine: clothing, kitchen equipment, sheets and towels, blankets, mirrors, tools, musical instruments, even a house to live in with all its furnishings. These and so many other goods would come right to the customer’s doorstep, no matter where they lived.

Even before Rosenwald made his fortune, he had a vision of someday giving it away. As a young man, he dreamed of earning $15,000 a year—and, he said, he knew what he would do with the money. His family could live nicely on one-third, and he would plow another third back into the business. He thought he would give away the last third. When the time came, Rosenwald did so, with a vigor and zest that came to define his public life. He gave famously to causes that helped African Americans, but also to Jewish projects, in America and abroad. He worked to expand medical care and improve medical education, public health and hospitals. His gifts enhanced the city of Chicago. He created the Museum of Science and Industry and the University of Chicago. He made possible Jane Addams’ operation at Hull House and Grace and Edith Abbott’s Immigrant Protective League, organizations that worked directly with the city’s poorest residents.

Rosenwald had a philosophy of giving. He never made donations to endowments because he fervently believed each generation had to tackle the needs of its own age, and that those who gave should not saddle future institutions with mandates conceived in the past. He refused to allow his name to be affixed to buildings or walls, and did not want it formally and permanently attached to projects that would persist beyond his lifetime. When in 1917 he organized his foundation, the Julius Rosenwald Fund, he set it up to expire 25 years after his death and charged it with spending down the principal. Let his children, he argued, who would be wealthy indeed, create and support the organizations and institutions that they wanted to advance—not the ones he might have foisted on them.

Rosenwald did not shy away from publicly proclaiming his gifts and their scale. Ever the civic activist, he believed that announcing how much he planned to give might inspire others—particularly others with means—to act likewise. He may have been the first giver in American history to implement the match. Rosenwald would announce, with bravado, that he planned to give whatever amount to whichever undertaking, but only if others collectively raised an equal amount. He operated on the logic that supporting the public made a giver a better person—and thus, by insisting on the match, he was helping his fellow citizens.

One famous gift demonstrates how Rosenwald put his principles to work: his massive project of building elementary schools for African American children in Southern states. He embarked on the effort in 1917; by the time of his death in 1932, he had funded almost 6,000 schools. They came to be known as Rosenwald Schools, though he had never wished that to be the case. He had wanted the institutions to be known by the names of the communities they served.

Other aspects of the school project more closely reflected his dictates. There was a match: Rosenwald would build only if states provided funds as well, and included the new schools for black children in the public system, supervising them just as they did the white schools. Rosenwald’s offer functioned as a way to entice the white Southern power structure to take responsibility for the education of black children, which he saw as a step towards equalizing resources. Similarly, Rosenwald asked African American residents to help by providing sweat equity, literally by building the schools. They could help by providing lumber from their sawmills or bricks from their kilns. They could provide housing for the teachers who would come to staff the schools.

Rosenwald repeated this pattern time and time again, to the ultimate benefit of millions across the nation. The catalog of his good works, all fueled by a belief in the power of consumption, augments his portrait as a grateful American of immigrant parentage who believed that wealth brought obligations; that being a good American involved making the country a better place; and that he, a very lucky individual, had a responsibility to empower and inspire others.