Does time—even an entire generation or multiple generations—actually heal all wounds? The question is a prominent one for trauma experts who study the Holocaust.

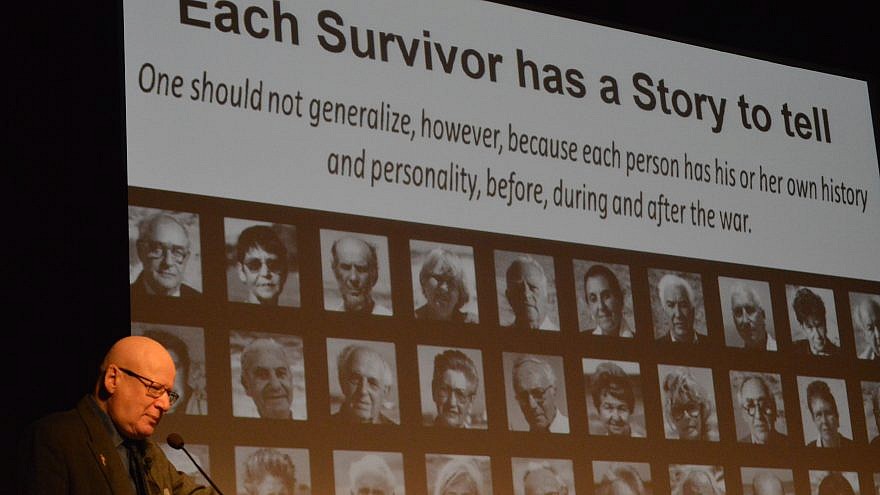

Natan Kellermann, Ph.D., a leading researcher on transgenerational trauma and the Holocaust, explained during a recent conference devoted to the subject that “there are those [Holocaust-era wounds] that remain painfully open,” and that the “suffering of survivors didn’t end with the war.”

On Feb. 7, nearly 200 people gathered at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles for “Inheriting Genocide,” a daylong symposium on transgenerational trauma with a focus on survivors of the Holocaust and the Armenian genocide survivor populations.

The study of transgenerational trauma—the transfer of trauma from those who experienced it to future generations—first began in the 1960s with children of Holocaust survivors in Canada. Kellerman and many other experts also believe the suffering it didn’t end with survivors.

When his PowerPoint presentation reached a slide of an arm with Auschwitz concentration camp tattoo numbers, Kellermann said, “I think of myself as a small child, maybe 5 years old. As a child I see this arm, maybe the arm of my mother or my father. I think how come my parent has a number on their arm? From where did it come? Who gave it to them? At this point, it might not be such a big deal. But I can imagine a child who lives with that number forever.”

Born in Sweden to Holocaust survivors, Kellermann has dedicated more than 30 years of his life to studying transgenerational trauma. He is the former chief clinical psychologist and current director of research for AMCHA, the largest provider of mental-health and social-support services for Holocaust survivors in Israel, reaching more than 10,000 clients.

Kellermann also spoke about decades of research and controlled studies that have yielded biological markers in second- and third-generation trauma survivors. Those studies, in addition to MRI scans, have shown that certain stress responses in the brain are inherited, causing anxiety, depressive episodes and varying post-traumatic-stress disorder symptoms.

But Kellermann emphasized that much of this situation is difficult to identify and explain, likening it to the lingering or delayed effects of nuclear waste or “radioactive effects.” He did note, however, that Holocaust survivors and their children aren’t disproportionately or more seriously affected than other trauma survivor groups.

Salpi Ghazarian, director of the University of Southern California’s Institute of Armenian Studies, spoke about the importance of including a diverse array of narratives in the discussion around transgenerational trauma. “The sooner we all realize so much of who we are is similar, including those of us who have suffered immense injustice, whether it’s descendants of slaves, Native Americans, Jews or Armenians, the easier it’ll be to do what we all want—to see that this kind of injustice doesn’t continue,” said Ghazarian, whose grandmother survived the genocide against Armenians perpetrated by the Ottoman government in the early 20th century.

Dr. Andrei Novac, a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Irvine, did point out a specific trend relevant to descendants of Holocaust survivors, who made up a sizable portion of his audience based upon a show of hands.

“Statistics show that, of course, as [Kellermann] said, children of Holocaust survivors don’t have a specific pathology, but in fact, socially, in some subpopulations they are more likely to be professionals, be successful, and join the health and mental-health fields, or the ‘helping professions,’ ” said Novac.

The next show of hands among the crowd aimed to determine how many attendees were mental-health professionals—and almost every hand rose.

Two of them belonged to Connie and Noah Marcos, both children of Holocaust survivors who have raised three of their own children together.

“You can imagine the level of transgenerational trauma present in our family,” said Connie, a practicing psychiatrist in Los Angeles.

Her husband, Noah, chief medical officer at the nonprofit Los Angeles Jewish Home, which cares for a group of residents that has the highest proportion of Holocaust survivors of any similar provider in its county, believes that the conversation around transgenerational trauma is just getting started.

“It’s a fascinating topic, and I think it will continue to grow because the stimulus is always happening. Every week, you hear about different events, attacks on different groups happening around the world,” he said.

During a discussion featuring service providers, including social workers and psychologists who work closely with trauma-survivor populations, panelists relayed statistics concerning the challenges facing Holocaust survivors, including how there are more than 127,000 survivors in the United States, 25 percent of whom live below the poverty line.

The panel highlighted organizations like Jewish Family Service of Los Angeles, which offers services for low-income Holocaust survivors, including counseling, assistance with reparations and claim forms, intergenerational programs, crisis intervention, social programming and financial assistance. That organization, along with USC’s Edward R. Roybal Institute on Aging, the Jewish Federations of North America, the Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles and the Museum of Tolerance, co-sponsored the symposium.

Eli Veitzer, president and CEO of JFS of Los Angeles President and CEO, said the event “has been building bridges with other [social-service] provider communities, including the Armenian provider community. This is how we’re beginning to learn from one another about the work we’re doing, best practices and the communities we’re serving.”