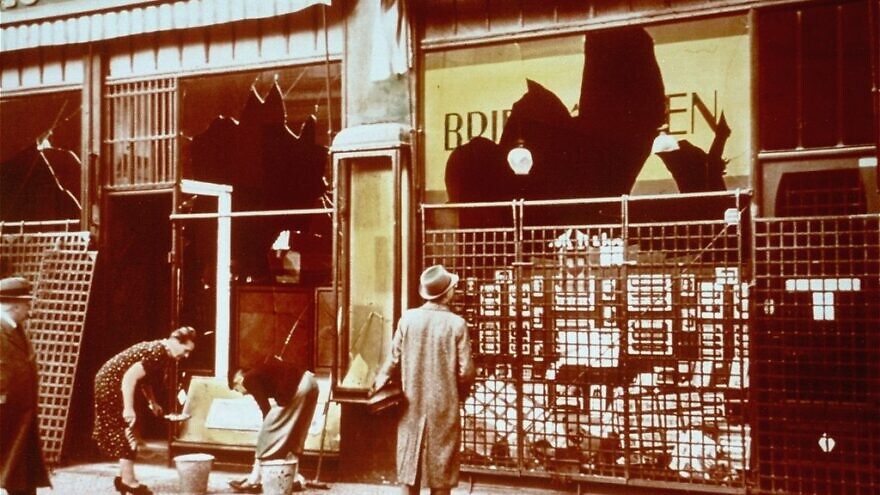

This week Germany marks the 81st anniversary of Kristallnacht, “The Night of Broken Glass.” The nationwide Nazi pogrom against that country’s Jewish community took place on Nov. 9-10, 1938, and is chiefly remembered for the destruction of so many Jewish-owned stores, buildings and synagogues—debris filling the streets with shards of glass from shattered windows and doors.

Kristallnacht is often described as the harbinger of the Holocaust that would soon consume the lives of 6 million Jewish men, women and children during the following years at the hands of Germans and their collaborators. But it might more accurately be referred to as the culmination of a process of demonization and marginalization by the Nazi regime that led to a national demonstration of intolerance and violence. Within a few years, the horror of the blood shed by the murderers would eclipse the shock of the Kristallnacht pogrom. But what must be understood about the events of November 1938 is that prior to that event, it was still possible to pretend that Germany was a civilized nation, even if Adolf Hitler and his followers, who took power in January 1933, spoke and acted like barbarians.

In 2019, the significance of this date is not in doubt. What is in question is whether it should serve as a measuring stick for us to evaluate today’s crisis of anti-Semitism. After shootings in synagogues in Pittsburgh and Poway, Calif., and the brazen attack last month on a synagogue in Halle, Germany, as well as a host of other incidents throughout Europe, it’s clear that the rising tide of anti-Semitism that has swept over the globe in recent years is not abating. Violence from the far right aimed at Jews has become a fact of life that shouldn’t be ignored.

Meanwhile, the demonization of Jews and Israel from the left has also become a part of mainstream discourse in Europe. It is also finding a foothold in the United States as BDS advocates have become louder and shockingly prominent in the form of two members of Congress: Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) and Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), who are lionized by the press as victims of Islamophobia rather than hatemongers.

To state that doesn’t gainsay the fact that Jewish life is under siege in Europe, as even well-meaning government officials have gone so far as to tell German and French Jews not to wear identifying clothing, like kipahs, or jewelry, like Star of David necklaces, on the streets so as not to make themselves targets. Nor does it minimize the threat from terrorist groups or anti-Semitic regimes like that of Iran, which still hopes to acquire nuclear weapons and therefore place the one Jewish state on the planet in peril of being annihilated. Fears about Britain being ruled by an anti-Semite like Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn are similarly justified.

But the problem in Europe is not that the continent is about to fall into the hands of Nazis. It’s that only several decades after the Holocaust, the world is still awash in anti-Semitism that legitimizes the ongoing war on Israel and Zionism, and might one day engender more hatred and violence elsewhere if left unchecked.

Our problem is not recognizing that anti-Semitism exists, but how to calibrate our response so as to avoid the twin perils of hysteria and complacence.

Kristallnacht wasn’t so much the beginning of Nazi crimes against the Jews—discrimination, arbitrary imprisonment and violence long predated that moment. But it was the point of no return beyond which foreign observers could no longer deceive themselves about the nature of the regime and what it was capable of doing. Before then, even those who were not hostile to Jews—plus some Jews themselves, including those who remained loyal to their German homeland despite the fact that it was painfully clear their love was not requited—could see Hitler’s rise as an aberration, a passing phase that would soon be either defeated or absorbed into less dangerous movements. Until then, Nazi Germany could still be, albeit with difficulty, spoken of as somehow connected to the Germany that was at the heart of European high culture and science, rather than barbarism.

Yet to think clearly about Kristallnacht requires us to be both vigilant and realistic about the nature of contemporary anti-Semitism. You don’t have to believe that a new Auschwitz is possible in the near future to understand that Jew-haters on the right, as well as their strange Islamist bedfellows, would, if they could, repeat the horrors of the past. What they are capable of doing in the present is bad enough in terms of their efforts to demonize Israel and its Jewish supporters without resorting to hyperbole that undermines any effort to raise awareness of the problem.

Nor does one enhance Jewish security by speaking of the threat from white supremacists as having the kind of support that the Nazis possessed from a massive percentage of the Germany electorate. Today’s far-right-wing killers are largely isolated politically and can count on no support from the political establishment in Germany or the United States.

Equally foolish is the attempt to link President Donald Trump to anti-Jewish violence, ignoring his pro-Israel record and repeated condemnations of white supremacists.

What is required of our Kristallnacht commemorations is a cool-headed willingness to call out hate wherever it occurs and to take whatever action is needed to ensure the safety of our communities. We must also be willing to understand that the Jews are not alone today the way they were in 1938. Nor, thanks to the existence of the State of Israel, are they powerless. Those who forget or misinterpret history so as to bolster foolish alarmism or dangerous complacence are not doing the Jews or the fight against hate any good.