Poland’s government won an important victory on the battleground of history last week. It succeeded in persuading the entertainment-streaming service Netflix to amend a newly released World War II-based documentary that implied, through one of its maps, that the six extermination centers built by the Nazis on Polish soil were located in an independent, sovereign country, rather than one under German occupation.

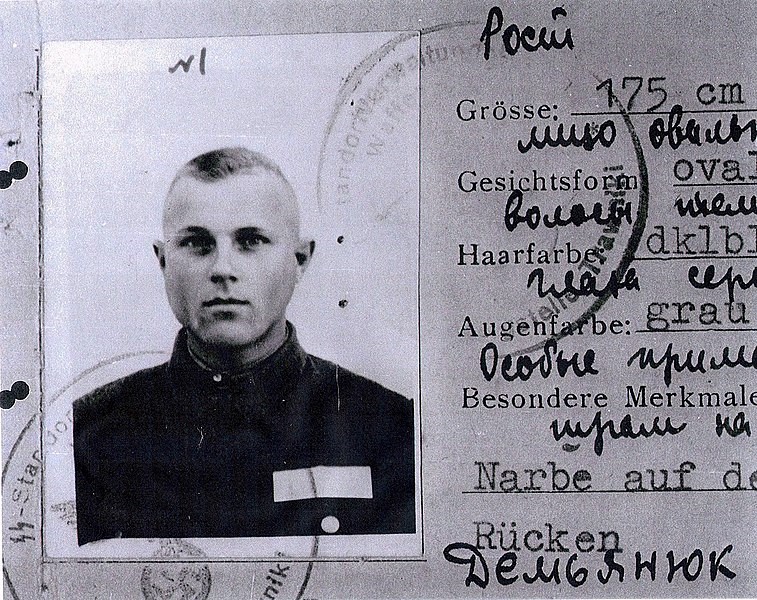

The offending map was included in “The Devil Next Door,” the widely praised documentary produced by the Netflix studios about Nazi war criminal John Demjanjuk. The former U.S. citizen was eventually convicted of assisting in the murder of 28,000 Jews at Sobibor—one of the six death factories constructed by Nazi Germany during its occupation of Poland, alongside Auschwitz, Chelmno, Treblinka, Belzec and Majdanek.

The problem with the map as rendered by Netflix was that it showed Poland as a unified country with sovereign borders—an absolute travesty of that country’s actual situation during World War II. As a furious chorus of Polish complaints led by Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki correctly pointed out, Poland was eliminated as a sovereign country through its partition at the hands of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. When the Germans invaded Poland, they did not install a puppet government, as was the norm elsewhere, but split the country into districts under direct German rule.

In a letter to Netflix CEO Reed Hastings, Morawiecki argued that viewers would be “deceived into believing that Poland was responsible for establishing and maintaining these camps, and for committing the crimes therein.”

Within a few days of receiving Morawiecki’s letter, Netflix conceded its error and promised to fix it. A revised map would “make it clearer that the extermination and concentration camps in Poland were built and operated by the German Nazi regime who invaded the country and occupied it from 1939-1945,” a statement from the company explained.

Poland’s leaders responded warmly. Writing on his own Facebook page, Morawiecki remarked that mistakes “are not always made of bad will, so it is worth talking constructively about correcting them.” Similarly, on Twitter, the Polish foreign ministry recorded its “appreciation” of Netflix’s attention to “difficult and important topics.” To anyone who isn’t tuned into the finer details of the Polish World War II debate—and that is most people—the spat with Netflix would seem to have been resolved by a welcome combination of sober historical research, mutual respect and an accent upon factual accuracy as the one element of the historical narrative that really matters.

Matters such as these, however, are rarely so simple. In Poland’s case, a legitimate complaint such as the one against Netflix also serves as a gateway for the very “rewriting of history” that so alarms Morawiecki, in terms of other critical aspects of the Nazi occupation.

For more than a decade, successive nationalist governments in Poland have made it a priority to assault some of the myths and careless formulations that have arisen around the Holocaust in Poland. For example, most Poles detest—and rightly so—the lazy description of Auschwitz as a “Polish concentration camp,” when it is more properly understood as a Nazi extermination camp built on occupied Polish soil by the invading Germans.

There are other vague, generally accepted notions about World War II that infuriate the Poles as well. On the thorny issue of collaboration with the Germans, two main points are made. Firstly, because Poland was under direct German occupation, historians cannot talk about “collaboration” in Poland as they would do with Croatia, France, Hungary and other European nations where puppet rulers were installed by the Nazis. Secondly, the risks of resisting the Nazis were far greater in Poland, where hiding or otherwise aiding a Jew would result in a sentence of death; the same offense against the Reich in France, by contrast, carried a much lighter sentence.

In Jewish circles, Polish anger over these issues has invariably received a sympathetic hearing. For example, Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust memorial, frowns upon the use of the phrase “Polish concentration camp,” as do the leading Jewish advocacy organizations—the American Jewish Committee, the World Jewish Congress and the Anti-Defamation League among them—that have built close relationships with Polish institutions since the end of the Cold War.

But accompanying these legitimate complaints is an aggressive tendency to police the research and discussion of the Holocaust so that any probing of Polish collaboration is denounced as historical revisionism. Through its Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) Law passed in 2017, to speak of Polish collaboration with the Nazis—the “Blue Police” units established by the Germans, the Szmalcownik bandits who preyed on Jews in hiding—is now a criminal offense. Increasingly, Polish historians emphasize that the 3 million Jews from Poland who were murdered by the Nazis were “Polish citizens,” which conveniently overlooks the widespread discrimination and violence directed at the Jews of pre-war Poland by thousands of their fellow Poles.

In tandem with these developments, Polish relations with Israel have nose-dived. In the furor over the passage of the IPN Act, several leading Holocaust historians accused Poland of callously whitewashing its reputation to suit its present nationalist agenda; the dispute even became a domestic issue, as Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was taken to task for allegedly prioritizing his desire for close trade and defense links with Poland over the truth of the Holocaust. Ironically, when, last February, Netanyahu did briefly mention the facts of Polish collaboration with the Nazis, the government in Warsaw promptly responded by canceling a summit of Eastern European nations that was being hosted by Israel.

When it comes to debating the issue of Holocaust collaboration, Poland will not settle for anything less than complete exoneration for its nation—a goal that doesn’t comport with the historical record. Just as it is true that there were no Polish units in the SS—unlike the Lithuanian, Ukrainian and other national units—it is also true that several thousand of the 3 million Polish Jews murdered by the Nazis were delivered to their executioners by non-Jewish Poles. Truth is not selective.