With the uptick in anti-Semitism in recent years, much more focus has been placed on the issue in both the Jewish and secular world in order to address it. However, a new survey has found that critical gaps exist in how younger generations know about the Holocaust, calling into question the effectiveness of current Holocaust education and how it can be used to grow awareness of modern anti-Semitism and hatred.

“The survey is the beginning of a conversation we must all have, not the end,” Matthew Bronfman, who chaired the Claims Conference task force behind the survey, told JNS. “It raises many questions and highlights many areas where scholarly and empirical research is required. Having said that, we are now eight decades past the Holocaust. The world has made a promise to Holocaust survivors to ‘never forget,’ but perhaps inevitably, the world has moved on.”

He added that “it’s understandable that people might focus on their immediate concerns. But the lessons of the Holocaust have eternal value—not only for the victims and their families, not only for the Jewish community, but for humanity.”

The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, also known as Claims Conference, commissioned the firm Schoen Cooperman Research to conduct the first-ever nationwide survey on Holocaust knowledge and awareness among millennials and Generation Z in each of the 50 states. Schoen Cooperman conducted 1,000 interviews nationwide with adults ages 18 to 39 between Feb. 26 and March 28, 2020. The margin of error for the national sample is 3 percent and higher in the state oversamples.

Nationally, 63 percent of respondents didn’t know that 6 million Jews were killed during the years of World War II and the Holocaust, and 36 percent believed that 2 million Jews or fewer were killed. Furthermore, of the more than 40,000 concentration camps and ghettos built in Europe during the Holocaust, 48 percent of respondents could not name a single one. While 44 percent were familiar with the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland and 6 percent knew the name Dachau, familiarity with Bergen-Belsen (3 percent), Buchenwald (1 percent) and Treblinka (1 percent) was significantly lacking.

The survey also addressed the topic of Holocaust denial. When asked whether the Holocaust did, in fact, take place, 10 percent said it did not happen or were not sure. Meanwhile, 23 percent of respondents either believed that the Holocaust did not happen, or that it took place but the number of Jews who died in it “has been greatly exaggerated,” or they were unsure.

A little more than one in 10 (12 percent) of U.S. millennials and Gen Z agreed that they had never heard of, or don’t think they’ve heard, of the word “Holocaust” before, and 15 percent of respondents thought it is acceptable for someone to have neo-Nazi views.

Also unsettling is that 59 percent agreed that “something like the Holocaust could happen again today.”

Regarding social-media’s role in spreading Holocaust misinformation, 49 percent said they have observed Holocaust denial or distortion on social media or elsewhere online, and 56 percent said they saw “Nazi symbols,” including flags with swastikas or pictures glorifying Adolf Hitler and Nazi soldiers, in their community and/or on social-media platforms within the past five years.

“The dual crisis of critical knowledge gaps, plus broad exposure to distortion and denial on the social-media apps that young Americans frequent, was the most alarming finding of the survey,” Arielle Confino, senior vice president at Schoen Cooperman, told JNS. “Social-media platforms and apps like Facebook and TikTok are undoubtedly serving as platforms for this and are clearly having an impact.”

‘A notable amount of misinformation’

Some 67 percent of U.S. millennials and Gen Z’ers said they first learned about the Holocaust in school, which underlines the important role that educational institutions in America play in Holocaust education.

A total of 80 percent agreed with the statement that “It is important to continue to teach about the Holocaust, in part, so it doesn’t happen again”; 64 percent believed Holocaust education should be compulsory at school; and 50 percent agreed that the lessons about the Holocaust are “mostly historically accurate, but could be better.”

While the respondents did not indicate how lessons could improve, Confino suggested “pivoting away from a survivor/memoir-centric model to one that pairs firsthand accounts with historical, geographical, sociological and political context to hopefully eliminate any questions about historical accuracy.”

Bronfman believes that while teachers are now making a dramatic switch to a new “virtual” learning environment due to the coronavirus pandemic, adaptations “can and should be applied to Holocaust education.”

“I’m thinking in particular of the vast amount of online resources freely available through Holocaust museums and other institutions,” he said. “We know that personalizing the Six Million, for example, is always crucial, and there are videos of survivors’ testimony that can be incorporated into classroom learning.”

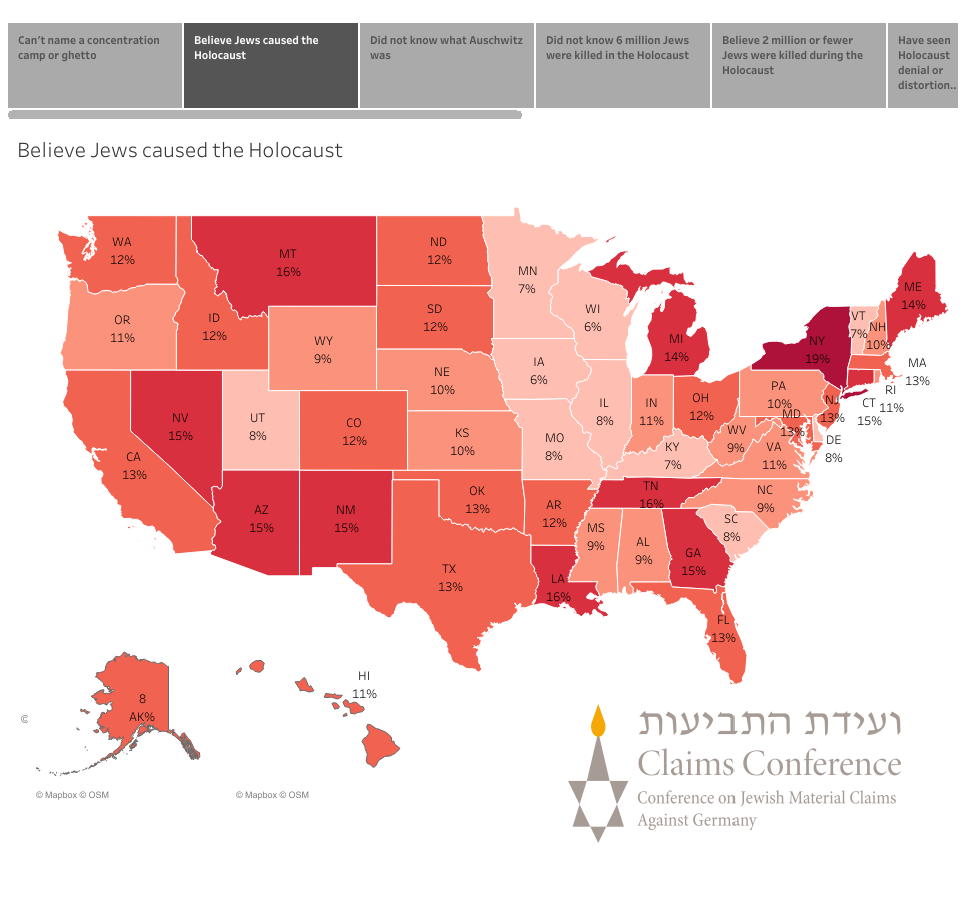

Although general support for Holocaust education existed among respondents, there remains a notable amount of misinformation about it among millennials and Gen Z. In the survey, 11 percent of respondents agreed that the Jews caused the Holocaust; 22 percent said the Holocaust was associated with World War I; and 32 percent were not familiar at all with the late famed Holocaust survivor, author and Nobel Prize laureate Elie Wiesel.

“It is my hope that these disparities in Holocaust knowledge will inspire a national movement to optimize the quality of Holocaust education and deploy it systematically across the country,” said Confino. “Currently, Holocaust curriculum is determined at the local level. And even in the states where Holocaust education is mandated, the quality of the lessons vary significantly from school to school as each locality sets its own school curriculum, and it is up to each individual teacher to decide how they want to teach the Holocaust.

“In my opinion, the current approach to Holocaust education in the United States … isn’t sufficient. We need to optimize Holocaust curriculum and teacher training with an emphasis on providing the necessary historical and geopolitical facts and context and deploy it systematically on a national level.”