In November 2020, many months after cutting all ties with Israel, and with the declaration of Israeli sovereignty in parts of Judea and Samaria off the table, the Palestinian Authority agreed to renew security and defense cooperation with the Jewish state. The formal announcement came after lengthy behind-the-scenes contacts. The person behind those talks, which went on even when ties between Jerusalem and Ramallah were severed, was the Coordinator for Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), IDF Maj. Gen. Kamil Abu Rokon.

In April, Abu Rokon is slated to finish a stormy three-year term as head of COGAT. For 42 years he has been following every twist and turn of the Palestinian system, and it’s doubtful that anyone else in Israel is as familiar with it as he is.

“But the last few years have been more complicated and problematic than anything I remember from the past,” he added.

‘Aid helps security’

The COVID-19 pandemic has piggybacked on the pre-existing crises in Gaza. Currently, unemployment in the coastal enclave is 45 percent. Electricity is available an average of 12 hours a day (16 in some areas)—a dramatic improvement compared to the four hours it had in the past.

Abu Rokon was a key partner in the process that led to this development, as the person who put together an agreement that stipulated that $8 million of the Qatari aid money sent to Gaza each month would go directly to pay Israeli energy companies that supply the diesel fuel to run the P.A.’s power plant.

According to Abu Rokon, the aid money is divided into three parts.

“$8 million goes to keep the power plant running; $10 million goes to help needy families, which get $100 each based on a list we approved; and the other $7 million goes to pay salaries of the civil servants who keep the public infrastructure in the Gaza Strip running,” he said.

Despite this aid, however, Abu Rokon describes the situation in the Strip as “a serious but stable humanitarian crisis.”

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency, for example, feeds 1.3 million people in Gaza a day, supplies schools for 300,000 children and employs 20,000 adults. Abu Rokon says that after the United States slashed funding for UNRWA, the organization was forced to “beg,” as he put it, for an extension for its payments and other commitments.

Abu Rokon has been fighting to increase Gaza’s fishing zone to allow the residents a way to make a living, and he is also battling to have Gazan laborers allowed into Israel.

“When I took over the role, 1,800 merchants would leave Gaza for Israel every day, and by the time COVID hit that number was up to 7,000. I thought we should let more in. I said, ‘Let me bring in 10,000 laborers a day, and I’ll get you a deal with Gaza.’ That didn’t happen because of COVID, but also because the Shin Bet [security agency] objected to it out of concern that Israel allowing in workers would be exploited to carry out terrorist attacks from Gaza.”

According to Abu Rokon, Gaza has been weathering the pandemic quite well in terms of public health, something he attributes to stricter discipline there.

“To everyone’s surprise, the situation there is fantastic. There are almost no fatalities, and there is very little spread,” he said.

“Gaza isn’t Judea and Samaria. In Judea and Samaria, the Palestinians behave like people do in Israel—they walk around, come and go, have parties. In Gaza, there is strict discipline, so they have a very low COVID rate,” he added.

Asked whether a deal could nevertheless be cut with Hamas to exchange vaccines for the return of Israeli civilians and the bodies of Israeli soldiers being held by the terror group, Abu Rokon said that while in his opinion Hamas would agree to link the two things, doing so would not be advisable.

“It’s a very sensitive issue,” he said.

Israel should make humanitarian aid to Gaza conditional upon a solution to the problem of its missing and captive citizens, he said. He quoted former IDF Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. (res.) Gadi Eisenkot, who said that Israel should freely help the Gazans in five basic areas: electricity, water, sewage, food and health care.

“I think that this aid also helps our security,” he said, adding, “The protests at the border fence started because of the distress in Gaza, and our role is also to keep southern Israel calm.”

In the meantime, the Gazans have started receiving vaccines from other sources, some of which come from the quota Israel delivered to the P.A., and some from donations from the rest of the world. Mohammad Dahlan, a rival to Palestinian Authority leader Mahmoud Abbas, sent them 25,000 vaccine doses, and the World Health Organization intends to send them 40,000 more. Abu Rokon does not think that Israel needs to vaccinate everyone in Gaza, but does support a vaccine initiative for everyone in Judea and Samaria.

Q: Explain that.

A: The Gaza Strip is closed off, but Israel and Judea and Samaria are one epidemiological unit. Therefore, we started vaccinating the Palestinians who work in Israel. By the way, we aren’t paying for those vaccines, the money comes from part of the taxes their employers pay on their behalf. But we made it clear to the Palestinians that it was their responsibility to get vaccinated.

Q: Why?

A: Because we don’t need the world to come down on us. We don’t control them. They’re an independent entity.

An uprising in Gaza? No chance.

“A year and a half ago, there was an attempt to challenge them [Hamas], and Hamas really gave it to them. Hamas is very powerful, and people don’t dare stick their necks out. I don’t think it will happen,” said Abu Rokon regarding the possibility of a popular revolt in Gaza.

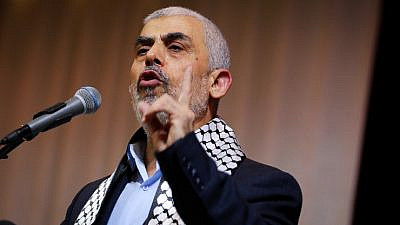

Last week, Gaza held another round of Hamas elections, that resulted in Yahya Sinwar beating Nizar Awadallah in a close race.

“The old guard united against the existing system and put up a fight. I’m just reminding you that Awadallah was behind the Gilad Schalit incident,” said Abu Rokon.

Q: Which of them would have been better for Israel?

A: Neither. They’re a terrorist organization, and that’s how they should be treated. It’s imprinted on their brains.

Q: Does Hamas want a long-term ceasefire deal with Israel?

A: I don’t think it’s an option. First, the problem of the missing and captives has to be solved, then they need to acknowledge existing agreements and say they reject terrorism. At the moment, they won’t accept these terms, so they’re a terrorist organization.

Q: It won’t happen?

A: In my opinion, no. They are motivated by hardline Islamist ideology. Their main goal right now is to take control of Judea and Samaria and establish an Islamist state there.

Q: In the meantime, they are screwing over their own citizens.

A: There are quite a few projects that could move ahead. A gas pipeline to Gaza, industrial zones. We’ve made it clear to them and every possible player that these won’t happen until the matter of our missing and captives is resolved.

Q: And what is their answer?

A: They don’t answer. They’re stuck in their ideology. Why do they take money and dig attack tunnels rather than investing in hospitals?

Palestinian elections

For now, the main challenge he foresees is the upcoming Palestinian general election, set for May 22.

“Hamas really wants these elections, so they’re going along with things that they could have insisted on having their own way, like legal oversight, because their goal is to get into Judea and Samaria. They’ll cooperate with anything that can lead them there,” he said.

The current expectation is that Hamas will win some 40 percent of the vote, with 60 percent going to Fatah, he said. He noted that the results of the 2006 election defied expectations and said, “There could be a surprise this time, too.”

Such a surprise, he explained, would not occur because of popular support for Hamas, but because of the Palestinian public’s alienation from the P.A., internal rifts in Fatah and Hamas’s well-oiled political machine.

“They [Hamas] don’t’ have a majority among the population, but they are very well organized and they have a goal,” he said.

Abu Rukun says that Israel is not intervening in the internal Palestinian matter, but he does not envision a situation in which Israel would continue to abide by agreements made with the P.A. if it were under the leadership of Hamas.

“If that happens, automatically there would be no … security coordination, so we would have to ask ourselves what the agreements were still worth,” he said.

Q: And Abbas doesn’t understand that?

A: Abbas is 86, and he doesn’t want to be remembered as the one who split the Palestinians and lost the Gaza Strip. He is busy with his legacy. He also wants to keep all the factions in the Palestinian political system, and apparently [to] curry favor with the new U.S. administration, which supports democratic processes. Other than that, he’s a little detached. It reminds me of what happened to [former Egyptian President Hosni] Mubarak before the Arab Spring.

Q: Explain.

A: The people who bring things to him and issue things in his name don’t understand the alienation between them and the Palestinian population.

Q: But the population in Judea and Samaria wants to live in freedom, not under a radical Islamist regime like in Gaza.

A: That’s true, but most people are busy with their day-to-day lives. I assume that most of them don’t really believe that Hamas would take over. They’re busy with themselves.

Q: If Hamas wins the elections, what should Israel do?

A: We’re preparing for every scenario, including the possibility of a rise in terrorism. I remind you that even when the P.A. cut ties with us last year, we continued to function and provided solutions.

Q: Whom do you expect will succeed Abbas as P.A. leader?

A: I am betting on Nasser al-Kidwa [Yasser Arafat’s nephew, who represented the Palestinians in the United Nations and was the P.A.’s former foreign minister].”

Q: Not Mohammad Dahlan?

A: I don’t see any chance of that. Hamas is letting him bring people into Gaza and toss money around there, but they aren’t suckers, and he has almost no traction in Judea and Samaria.

‘The Palestinians are like us’

Abu Rokon, 62, lives in Isfiya, a Druze-majority town in the Haifa region. He has three children and three grandchildren (“one of them named Kamil, after me”). April will mark his third departure from the IDF, and he hasn’t yet decided what he will do next.

“At the moment, I don’t think I’ll hold another public position,” he said.

He enjoys very good relations with the top P.A. brass.

“When Naftali Bennett was defense minister, he told me they loved me. I said that was right, and that I used it for the sake of Israel’s security interests.”

He tells his staff that their job is to prevent a humanitarian crisis among the Palestinians, “Because it would reach us.”

According to Abu Rokon, the Palestinians—after an initial angry response—accepted the Abraham Accords and are now expecting them to result in aid for themselves. But anyone who thinks that they will demonstrate flexibility and become willing to make political concessions, he said, should think again.

“Unfortunately, they are losing time. Soon it won’t be possible to do anything,” he says.

Q: Is it solvable? Is there willingness?

A: Where, with us or with them?

Q: You handle “them.”

A: Yes. I think that they really want to make progress.

Q: Their actions don’t indicate that. Look at how they went to The Hague.

A: They did that because of the impasse, and because they wanted to shake up the system and exert some influence. I have no doubt that our military is the most moral in the world, and if The Hague has any questions about it, they should look into what [Syrian President Bashar] Assad did or what they’re doing in Iran, and then get back to us.

Q: Do they take an interest in our election? Are they involved in our elections?

A: At every meeting, they take care to say that Israel’s elections are an Israeli matter. There is Muhammad al-Madani, Abbas’s adviser on Israeli society. In my opinion, he is in touch with the Israeli side, but I don’t think they’re really involved.

Q: What does the average Israeli reading this interview not know about the Palestinians?

A: They are an educated people, similar to us. It’s not Jordan or Egypt. We live close to one another, work with each other. The Palestinians aren’t the devil. Most of them are good people, who just want to live. The young generation wants to be left alone. They want rights. They want to live like any other young people in the West. They want economic security. I was in Hebron two weeks ago. Everything there is broken—the markets, the shopping malls. All the display windows. It’s like Istanbul.

Q: You’re basically saying that what the accords didn’t do, economics will.

A: If I were a Palestinian, I probably wouldn’t say that, because they have national aspirations, but the economy is definitely the major thing. In 2030, 3 million people will be living in the Gaza Strip. We need to think two steps ahead. The economy leads to stable security, and our job is to give the political echelon the flexibility and the freedom to work. I think that there is an opportunity right now to move toward bigger things with the Palestinians.

This article first appeared in Israel Hayom.