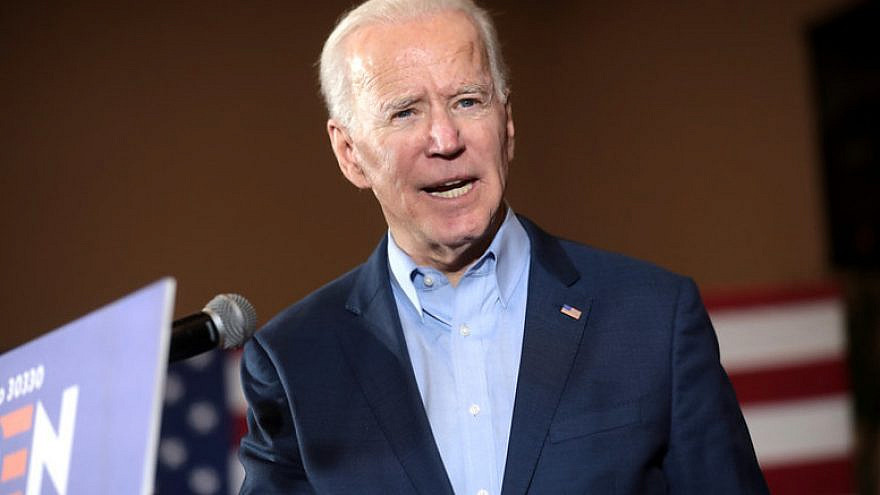

As he begins his second year in office this week, President Joe Biden looks toward the horizon and sees multiple challenges and threats. Three of the most worrisome:

Russia’s strongman, President Vladimir Putin, having taken the Crimean Peninsula and Donbas region from neighboring Ukraine now has troops poised for a possible further invasion of that former Soviet state.

Iran’s strongman, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who commands military proxies in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and Yemen, is continuing to develop nuclear weapons, which are key to furthering his neo-imperialist ambitions.

China’s strongman, President Xi Jinping, having stamped his boot on the people of Hong Kong, is now considering the deployment of his increasingly powerful military to do the same to the people of Taiwan.

In a fiery speech last week, Biden boasted that he’s “worked in foreign policy my whole life.” He warned of forces “that value power over principle,” pose a “grave threat” to “our democracy,” promote “subversion” and are possibly preparing for an “onslaught.” We must choose “democracy over autocracy, light over shadows, justice over injustice!” he declared.

What are we to make of such rhetoric? An election year has begun, and Biden would doubtless prefer not to talk about the fiasco of the Afghanistan surrender and withdrawal, the absence of security on the Mexican border, the highest inflation rate in 40 years, unionized teachers refusing to return to the classroom and confused pandemic policies.

But does he sincerely believe that those who oppose a bill to nationalize election procedures are, as he put it, “on the side” of Jefferson Davis, the rebel leader and slavery defender, while those who agree with him are “on the side of Abraham Lincoln”?

He went on to pledge that he would fight “all enemies—foreign and, yes, domestic”—equating elected American lawmakers with Putin, Khamenei and Xi.

Beyond slandering his former colleagues, such comments trivialize the life-and-death crises in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Asia. After all his years on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, is it possible that Biden doesn’t get that?

Whatever the answer, Putin, Xi and Khamenei must be mightily encouraged to see the American house continuing to divide. They must be pleasantly surprised to hear Biden say that America lacks “voting rights,” will fail without his “reforms” and that the millions of Americans who disagree are racists and traitors. That sounds not unlike the messages they’ve long been propagating about the American experiment.

Over the days since the Atlanta speech, criticism of the president has come from across the political spectrum. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell called Biden’s remarks “incorrect, incoherent and beneath his office.” Sen. Mitt Romney, a moderate Republican, lamented that Biden was going “down the same tragic road taken by President Trump, casting doubt on the reliability of American elections.” Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, a moderate Democrat, rebuked Biden for “pressuring us to see our fellow Americans as enemies.” Sen. Dick Durbin, a Democrat of the left, acknowledged that the president “went a little too far.”

If Biden’s political advisers are worth their salt, they’ll urge him to stop denigrating Americans who differ with him as … well, “deplorable” is the word that comes to mind. If he does not change direction, invitations to campaign with Democratic candidates in competitive districts are likely to be few and far between.

More consequentially, the president’s national security and foreign policies require significant adjustment if he is to do better in 2022 than he did in 2021. That should start with the recognition that America’s enemies are making common cause—cheering each other’s victories and building on them. Deterrence cannot be achieved simply by sending diplomats to talk fests at posh hotels while declaring, “America is back!”

Among the most urgently needed actions right now: Supplying Ukraine and Taiwan with the military equipment and weapons needed to make them “porcupines”—difficult for an invader to digest.

If the Ukrainian and Taiwanese leaders have the means to mount a prolonged and determined defense of their homelands, Putin and Xi may conclude that “strategic patience” is preferable to what Lenin called “adventurism.”

As for Iran’s rulers, Biden should understand by now that attempts to appease, bribe or seduce them will be unavailing. My colleague at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, Mark Dubowitz, and former Pentagon senior adviser Matthew Kroenig made the case in a Wall Street Journal op-ed last week for a realistic alternative: “coercive diplomacy.” That means “putting the military option back on the table, along with a renewed sanctions offensive.” Without those tools, American diplomats have no leverage.

More broadly, the president’s highest priority should be ensuring that the United States remains significantly more powerful—both militarily and economically—than its adversaries. The strongmen in Moscow, Tehran and Beijing find weakness provocative—maybe irresistible.

One more point: Biden won the White House largely because millions of people thought he would be “sane and normal and principled”—as New York Times columnist Gail Collins described him the day before the Atlanta speech (which was anything but). They certainly expected he’d know better than to confuse political opponents in Washington with predators in the global jungle.

Many people also expected he’d at least attempt to reunite an increasingly polarized nation. As he begins his second year in office, he’d be wise to consider what he must do—and what he absolutely must not do—if he is to have any chance of accomplishing that worthy mission.

Clifford D. May is founder and president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), and a columnist for The Washington Times.