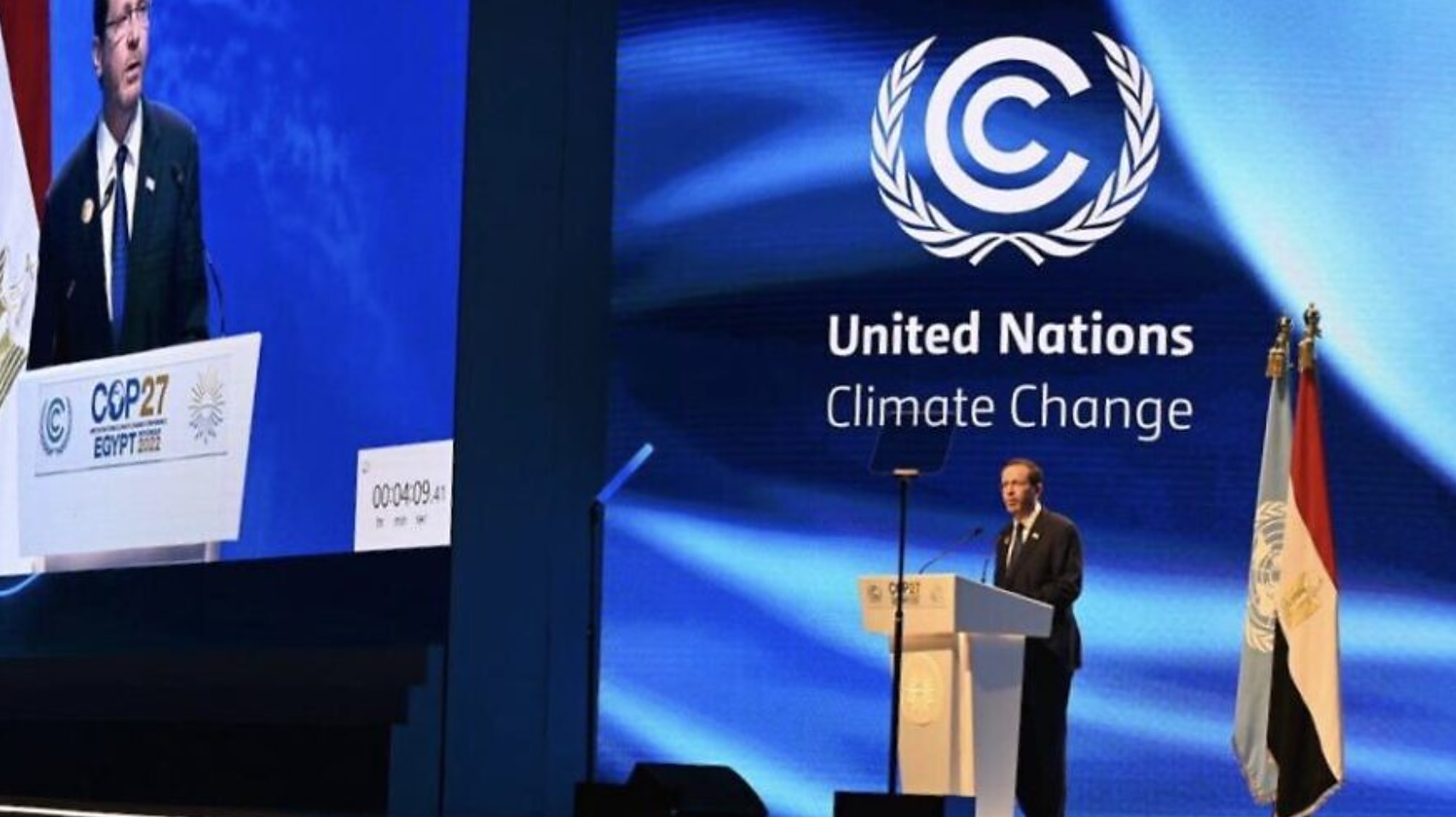

Israeli President Isaac Herzog went beyond reaffirming his country’s 2021 commitment to fight climate change at the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27) in Egypt at Sharm el-Sheikh.

On Nov. 7, Herzog presented a far-reaching vision of a sustainable energy infrastructure serving as the foundation for Middle East Peace. In a spin on Shimon Peres’s New Middle East, he termed it a “Renewable Middle East.”

“I intend to spearhead the development of what I term a Renewable Middle East—a regional ecosystem of sustainable peace,” Herzog said.

“I envision that in the foreseeable future the solar energy produced in the deserts of the Middle East will be available for export to Europe, Asia, and Africa,” he said. “I believe that the entire Middle East, all Middle Eastern nations, abundant with sun and technology, will have the ability to connect the rest of the world to a magnificent source of renewable energy.”

Ambassador Gideon Bachar, special envoy for climate change and sustainability at the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, told JNS that it’s not just rhetoric. “Creating regional resilience to climate change, working together, collaborating, finding solutions between Israel and its neighbors in the region in general is Israel’s policy,” he said. He offered the water-for-energy agreement signed between Jordan and Israel at the conference as an example.

Israel is a relative newcomer to climate change. In June 2021, then-Prime Minister Naftali Bennett announced that Israel would cut 85% of its carbon emissions from 2015 levels by 2050. At last year’s COP26 in Glasgow, Bennett upped the ante, pledging net zero emissions.

Israel debuted its first pavilion this year at the annual climate change conference, pushing various innovations. On Wednesday, the pavilion focused on Israeli space technologies that could address the climate crisis.

Bachar dismissed those pointing to Europe as a cautionary tale of what happens when traditional energy sources are rejected in favor of renewables, like wind and solar. Plunged into an energy crisis by the war in Ukraine, and fearing energy shortages in the approaching winter, Europe restarted coal plants and went on a natural gas buying spree, including from Israel.

“It’s only temporary,” Bachar assured. “Europe is doubling its efforts to go into renewables.”

However, consistently high energy prices have sparked fears not only of a citizenry struggling for warmth but of the literal deindustrialization of Europe as energy-intensive industries are looking to permanently relocate elsewhere, such as China.

In Israel, growing concerns about the wisdom of renewables prompted local scientists to found the Israeli Forum for Rational Environmentalism, a group seeking to provide a “more balanced and data-oriented discussion of climate.”

Yonatan Dubi, a chemistry professor at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and a leading member of the group, said Europe is a warning sign that Israel ignores at its peril. Of Herzog’s vision of a renewable Middle East he said, “It’s rainbows and unicorns.”

“I suggest that President Herzog spend a little bit more time learning about engineering, about the electrical grid…about the environmental harm of covering thousands and thousands of acres of land, and about transmission lines,” Dubi told JNS. “Regardless of how beautiful his vision is, at night the sun does not shine. Yet power is a necessity also at night. Therefore, this beautiful, hilarious solar power dream of his is useless.”

Dubi is concerned that deals coming out of COP27 could damage Israel in the long run. “Electricity is an essential component of life. If you can’t pay the electric bill, you will freeze to death in Europe and you will be poorer in Israel,” he said.

Noting that the Sharm el-Sheikh conference launched an initiative to help 4 billion people adapt to climate change, Dubi said that what people are forced to adapt to are the so-called climate change “solutions.” European countries have been forced to enact emergency measures, from tax cuts to cash handouts, to shield their citizens from soaring prices.

Ironically, Europe has an abundance of energy resources. It simply chose not to develop them in its pursuit of renewables, he said. In the end, it got hooked on cheap natural gas from Russia. He noted that Israel’s Ministry of Energy made a brief push toward renewables, but reality forced it to retreat. In December of last year, the ministry announced a stop to new offshore licenses for gas exploration to focus on renewables and by May had changed course as Europe begged it for gas.

Even some who are skeptical that climate change is a global danger have argued that there’s no harm in Israeli technologies benefiting from the effort to combat it. Dubi disagreed, saying that the Israeli government shouldn’t be in the business of steering technology. “Basic research is one thing,” he said. “The worst thing that can happen is that the government puts subsidies into this, like the Germans did. If you’re funneling money to this, you’re denying funding to something else. And, honestly, Israel doesn’t need this technology.”

He noted that Israel became the “start-up nation” despite the government, not because of it. (Israeli economists have argued that the country’s high-tech sector succeeded in part because it innovated too quickly for Israel’s infamous bureaucracy to catch up and regulate it.)

While the temptations for Israel to climb on the climate change bandwagon are myriad, Israel must resist, Dubi said. Tapping into the enormous wealth offered for solutions is only one temptation. He said there’s also the desire to save the world, “of doing good.” And in Israel’s specific case, it’s a pleasant change to feel the world’s welcome embrace after so often being targeted for criticism.

Dubi doesn’t doubt that Herzog is sincere in his belief that climate change is a threat to the planet, but he said Israel’s president is nonetheless misusing his position, meant to be symbolic, to advance a political goal. Indeed, Herzog is using his position to give climate change a sheen of being above politics “when this is totally about politics,” Dubi said.

“There was some NGO in Israel that gave a green score to the political parties to see how green they were, whatever that means in their eyes, and you can see the correlation between how left-wing a party is and how green it is. It’s clearly a political issue,” he said.

What’s more, it’s a political issue that’s very low among the public’s priorities, as evidenced by the failure of the far-left Meretz Party to cross the electoral threshold. “Fifty percent of their campaign was focusing on saving the planet,” he said. As a result, it will be difficult for the next minister of environmental protection to continue the policies of the current one. “It will be hard politically and hard to explain to the voters,” he said.

Dubi expects the new government to take a different direction. “I actually have some indications that this will be the case.”