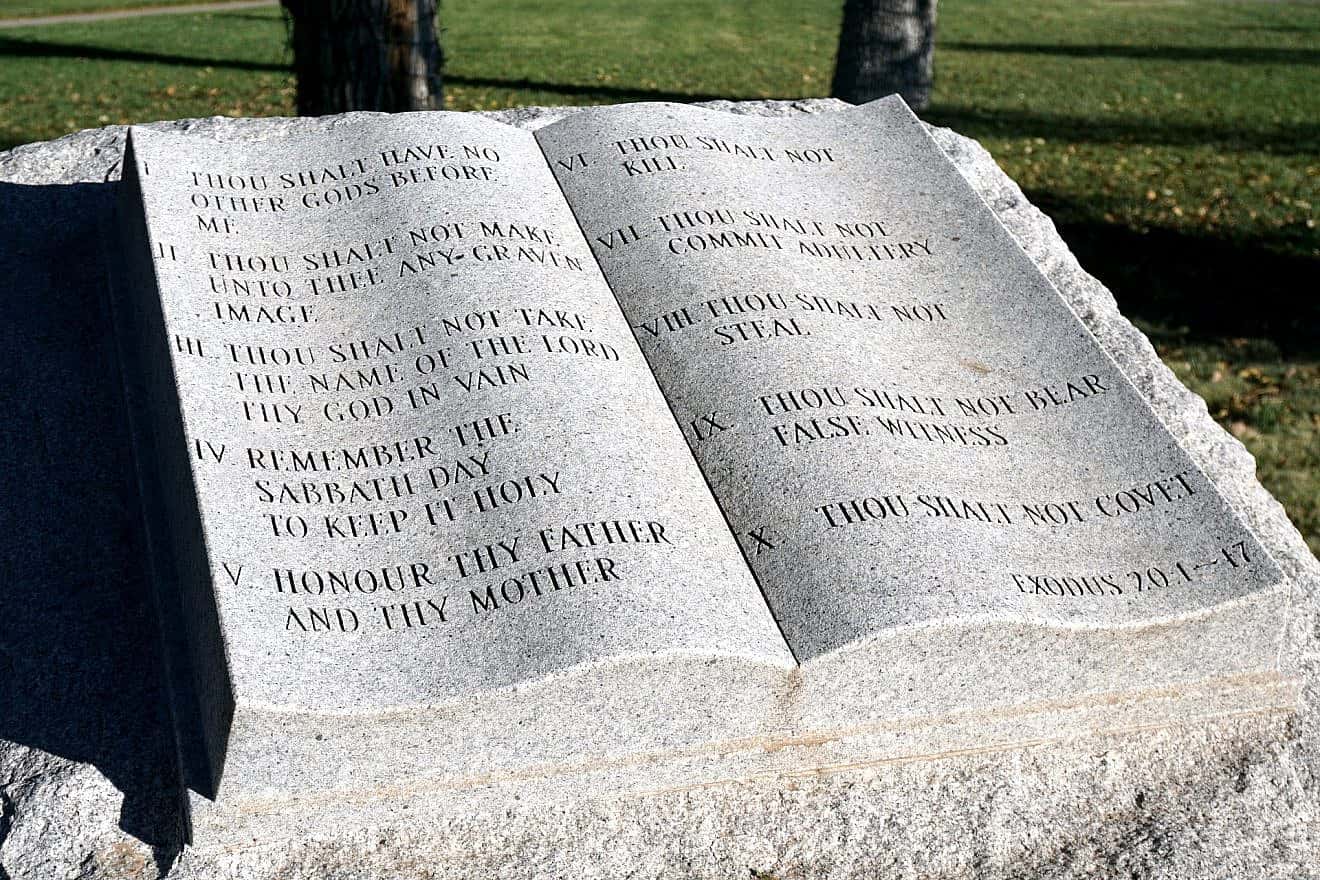

Let’s begin with the old saying that reminds us: “It’s the Ten Commandments, not the Ten Suggestions.”

This is much more than a joke. In fact, it is the foundation of our moral behavior.

I understand commandments like “Honor your father and mother,” “Thou shalt not murder, mess around or steal, etc.” But how can we be commanded to believe in God, which is the very first commandment? What if we don’t believe? What if we can’t believe? “I really would love to be a believer, rabbi, but I just can’t do it.” I’ve heard that from many people over the years.

How about the Tenth Commandment: “Thou shalt not covet”? How can we be commanded not to be jealous of someone else’s good fortune? Isn’t that a natural, spontaneous sensation?

How can we be commanded to feel or not to feel emotions? That our behavior can be controlled is plausible, but to control our emotions? To believe in a higher power when I am in doubt? When I am a natural skeptic? To refrain not just from taking but even desiring something other people have? Is that realistic? I can go along with commandments that seek to regulate our behavior, but mind control? Surely God, who gave us these commandments, understands the frailties of human nature.

There is a very important theological and philosophical principle that addresses these very questions. We subscribe to the belief that, if God commanded it, it must be possible to observe. The Creator understands human nature very well. He created us with all our strengths and weaknesses, our fortes and foibles. He knows us better than we know ourselves. If He tells us to do it, then He must know that we can do it. Otherwise, why would He waste our time and His?

It is a fundamental principle of faith that, while we all have a conscience, we also experience temptation. In classic theological language, we speak of a yetzer tov, our good inclination, and the yetzer hara, our evil inclination.

In Chassidic thought, the inclinations are usually referred to as our “Godly soul” and our “animalistic soul.” We all have both. No one is born a saint or a sinner. We have freedom of choice and we must decide which inner voice we will heed. We are all challenged daily to make the right choices in life. When faced with moral dilemmas, will we succumb to temptation or will conscience triumph? We really can go either way.

Think about the last time you did something you regretted. Take a simple, innocuous thing like eating that chocolate cake when you are on a diet. After you finished the cake, didn’t you want to kick yourself because deep down you knew that you could have resisted if you were only a bit more disciplined? I’ve had that experience all too often. It proves that we can exercise our freedom of choice with greater discipline if we want it badly enough. It’s no different when it comes to the more difficult and demanding tests of life.

If we really want to believe, we can develop and nurture the inner, latent faith we all possess. It is eminently doable. Faith needs nurturing. When we fulfill a mitzvah, we are feeding our faith; it gets stronger as we go along. The faith is there, but it may be dormant. We just need to uncover it.

My friend and colleague Rabbi Dovid Hazdan of Johannesburg tells the story of how, when Dr. Mosie Suzman died in 1994, Rabbi Hazdan came to the family home to conduct the shiva prayers. Dr. Mosie was a respected teacher, researcher and professor of medicine. His wife was the world-famous South African parliamentarian and anti-apartheid activist Helen Suzman. As Rabbi Hazdan walked through the front door, Helen told him: “I just want you to know, rabbi, that I don’t believe in God.”

The rabbi responded, “That’s OK, Helen. I don’t believe in atheists.”

Indeed, we do not. Every one of us has a neshama, a soul that is a part of God above. He gave it to us and it vivifies us. If we’re not in touch with it, it may be because we weren’t brought up that way, but it is there and very much accessible.

As it is with faith, the First Commandment, so is it with not coveting what others may have, which is the final commandment. Most of us have much more than our grandparents ever dreamed of having. When we see someone with more than we have, do we covet out of need or greed? We have so much to make us happy and content. Do we really need that car, gadget or whatever it is that beguiles us?

One of the social problems in the world today—and it is particularly pronounced here in South Africa—is prompted by the fact that the “haves” and “have-nots” live near each other and cross paths daily. South Africa has been described in recent times as “the most unequal country in the world.” The wealthiest and the poorest suburbs are not very far from each other. The many who live in poverty see the wealthy houses down the road and are envious. Often, they feel entitled to grab some of that wealth for themselves. There are many reasons why our crime rate is so high, but this social reality is one of them. We covet. We desire what others have and we do not.

But like faith, the Tenth Commandment is doable. We must be aware of our own inner struggles and realize that we always have the power to choose correctly. We really do. Please God, we will.