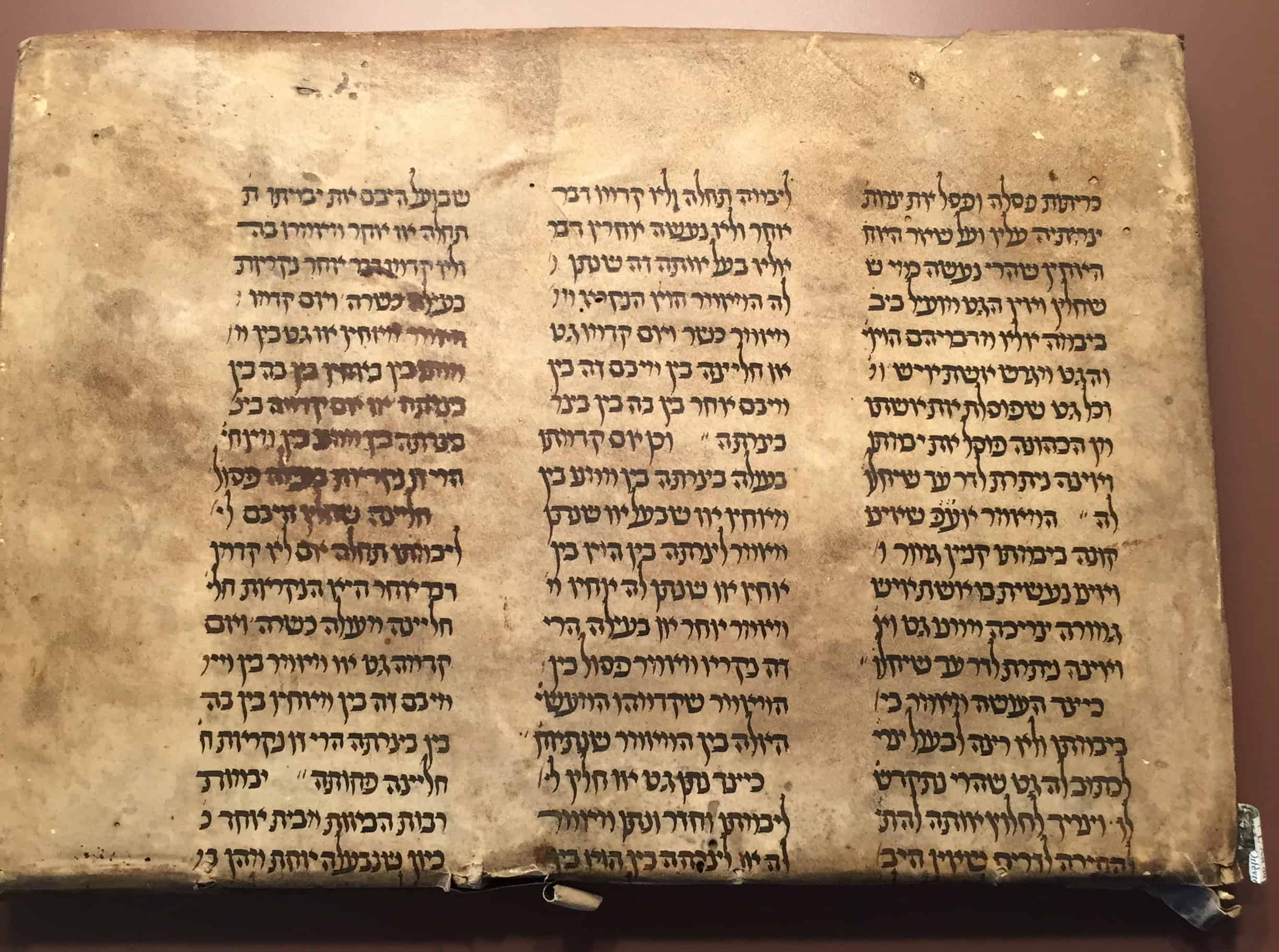

Marianna Stell was reshelving a book at the Library of Congress in 2017 when a “beautiful, even manuscript hand” on the shelf caught the reference librarian’s attention. After consulting with colleagues in the Hebraic section, she learned that the Hebrew text used to bind a late 16th-century Latin book came from the early 16th-century Beit Yosef.

The latter is “a monumental code of Jewish law” written by Rabbi Joseph Caro (1488-1575), “one of the most important Jewish figures of all time,” wrote Ann Brener, then a Hebraic specialist in the national library’s African and Middle Eastern division.

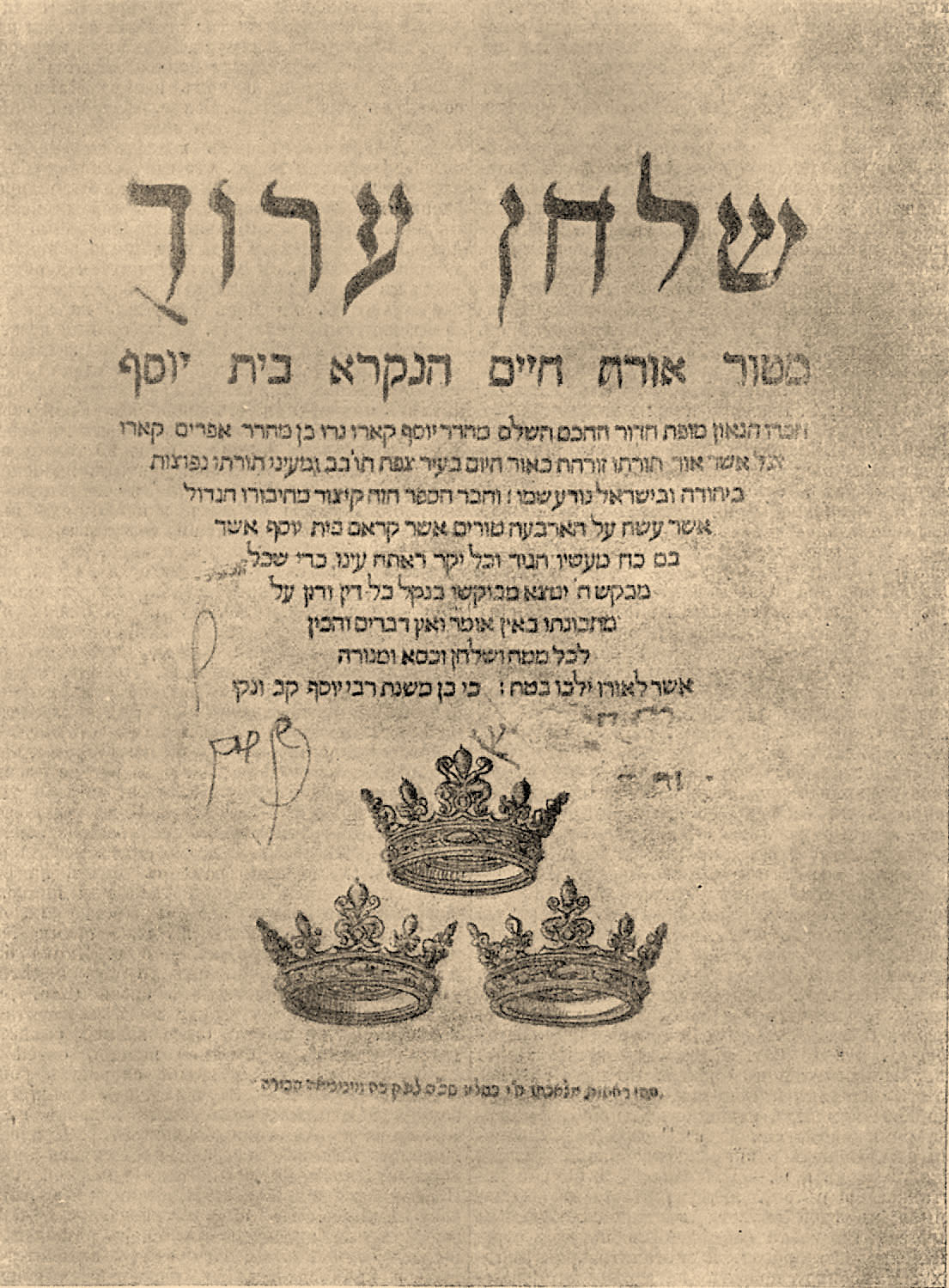

Caro is best known as the author of the Shulchan Aruch, wrote Brener, author of the 2024 book Books Like Sapphires: From the Library of Congress Judaica Collection. She suggested that the page of Caro’s work may have come to play supporting actor either due to its confiscation by ecclesiastical authorities, an anti-Jewish riot in Frankfurt where it was published or an Italian Hebrew print shop selling it for “waste binding.”

Next year is the 450th anniversary of Caro’s death, and experts told JNS that the table is set for another four-and-a-half centuries of prominence for Caro’s Shulchan Aruch, the “prepared table.”

Studying with angels

Caro, whose name is variously spelled in English, was born in Spain. Four years after his birth year, Spain expelled its Jewish population, and Caro’s family fled to Turkey. Some 34 years later, he moved to Israel, settling in Safed, the city associated with Jewish mysticism and the Kabbalah.

Like other major Sephardic rabbis, Caro had his feet planted firmly in both Jewish ritual law—halachah—and Kabbalah.

He is said to have prayed that he would die as a martyr, al kiddush Hashem, and he claimed in his esoteric diary Maggid Mesharim, “Preacher of Righteousness,” which was published posthumously in 1646, that he had angels for study partners. Beneath the Yosef Caro synagogue in Safed, a restoration of a study hall dating to Caro’s life, there is reportedly a subterranean space that will only be revealed in the messianic era.

“Together with his great assiduousness in Torah study, Rabbi Caro lived a somewhat ascetic life of numerous fasts and self-infliction,” wrote Moshe Miller on the Chabad.org website. He added that the angel, maggid, “promised him that he would have the merit of settling in Israel, and this promise was fulfilled,” although it also promised Caro “that he would merit to die a martyr’s death sanctifying God’s name,” which “did not transpire for an unspecified reason.”

Historic ‘halachist’

Shulchan Aruch is “widely considered to be the most important code of Jewish law until today,” according to the National Library of Israel. Caro’s work has been cited in multiple amicus curiae briefs submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Edward Fram, professor of history at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and author of the 2022 book The Codification of Jewish Law on the Cusp of Modernity, told JNS that Caro’s work remains timely “due to his scholarship, which is not to be underestimated, but no less significantly, because his work became a springboard for further discussion of the law, much of it in the margins of the printed text.”

“As for the future, one hopes that people will rise to the challenges that we will inevitably face, and perhaps develop new ideas for decision making and presentation of the law, just as Caro did in his time,” Fram told JNS.

“It’s an understatement to say that Rabbi Joseph Caro was a complex, fascinating and consequential Jewish scholar,” Alyssa Gray, professor of codes and responsa literature, and chair in rabbinics at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, told JNS.

Caro’s life “overlapped with and was influenced by significant world-historical shifts, notably the Spanish expulsion (1492), the early modern rise of the Ottoman Empire and a shift of the Jewish center of gravity from Europe to that Empire and the emergence of printing,” added Gray, who is co-editor of the Association for Jewish Studies journal AJS Review.

Gray told JNS that Caro’s “geographical movements are crucial to his legal work, the content of which similarly traverses a range of geographically (and chronologically) disparate Jewish legal cultures: Muslim and Christian Spain, Provence, Christian northern Europe and Italy, all refracted through the prism of his Ottoman and Eretz Israel contexts and communal involvements.”

Caro’s “analytic magnum opus” the Beit Yosef, offers a “detailed analysis” of the 14th-century Arabah Turim by Jacob ben Asher, with “Caro’s supplements, edits, revisions and post-14th-century updates,” according to Gray. Caro’s work uses ben Asher’s “as a convenient ‘hook’ on which to ‘hang’ its own aggregation, analysis and sifting of the entirety of the literature of Jewish law, to the extent Caro was able,” Gray added.

“Beit Yosef was to be a lawbook for the whole Jewish people,” Gray said. “The cultural, historical, geopolitical, intellectual and technological contexts of its writing were all serendipitously conducive to the possibility of realizing that aim, although, of course, Caro realized he had no authority to impose his lawbook outside of the circle of those over whom he may have had direct influence.”

Although Caro saw Beit Yosef as “the primary, more important lawbook,” its complexity likely led him to compose the Shulchan Aruch, which he saw, perhaps too modestly, as “a vehicle for presenting Beit Yosef’s conclusions ‘in a concise way,’” so that both seasons scholars and young students could use it regularly, according to Gray.

“However, contemporary scholarly study of the Shulchan Aruch shows that it is more than a mere digest,” Gray told JNS. “It is a thoughtfully composed work that reveals Caro’s own legal and religious tendencies, notably pertaining to care for the poor and the religious and Jewish legal prominence of Eretz Israel.”

“Caro did not intend Shulchan Aruch to be used for legal determination, but the Jewish people had other plans,” she said.

The work’s accessibility, coupled with its shorter length and the printing press, spread it more widely than Beit Yosef.

“Its author’s residence in Eretz Israel may also have added to its popularity,” Gray said. “Beit Yosef and Shulchan Aruch were the last law books seen as authoritative by practically the whole Jewish people, a process facilitated by the fairly quick addition of the Polish scholar Rabbi Moses Isserles’s notes to the printed Shulchan Aruch text and the later engagement with that work by a geographically and culturally diverse array of Jewish legal commentators in succeeding centuries.”

“The Shulchan Aruch in particular became—and still is—practically synonymous with ‘Jewish law,’” said Gray, who has no doubt that Jews “committed to studying and living according to Jewish law will continue to lean on the Shulchan Aruch.”

“Even if halachah-abiding Jews go back to viewing Shulchan Aruch the way Caro had initially hoped or if they even simply begin to view it as just one important lawbook among many, one is hard-pressed to imagine a world of Jewish legal observance and study without the presence of the Shulchan Aruch,” she said.

The ‘next Rav Yosef Caro’

Caro acknowledged readily that a “major dilemma” he faced composing Shulchan Aruch “was how to deal with the massive amount of rabbinic literature that had been produced after the completion of the Talmud 1,000 earlier,” Ephraim Kanarfogel, university professor of Jewish history, literature and law at Yeshiva University’s Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies, told JNS.

Caro based his “pithy” second major work, Shulchan Aruch, on his “discursive and encyclopedic” Beit Yosef commentary, according to Kanarfogel. “It is possible to suggest that the overwhelming success of the Shulchan Aruch rests in no small measure on the Beit Yosef which preceded it,” he said.

In his introduction to Beit Yosef, Caro suggested strongly that he “went out of his way to locate and include the views of Rishonim,” early rabbinic commentators, “everywhere, in well-known and lesser-known works,” according to Kanarfogel, who has published extensively on the history of Jewish law and on medieval Jewish history and rabbinic writings.

That “remarkable collection of sources” and Caro’s analyses “allowed him to then produce an all-encompassing, enduring code of Jewish law that could be assessed and appreciated by all its readers,” Kanarfogel said.

Unlike Maimonides, whose Mishneh Torah aimed to provide a “fully authoritative summation of Jewish law” but which listed its sources very rarely, Caro provided “most, if not all, of his sources, according to Kanarfogel.

“Subsequent halachists have dealt with, and will continue to deal with, the ongoing proliferation of halachic materials as the generations move forward,” he said, noting that Jewish law is disseminated today on computer files as well as other published forms.

“The ‘next Rav Yosef Caro’ will need to be someone not only of remarkable erudition, vision and piety, but also one who can effectively determine, as Rav Yosef Caro did, the best way to locate, organize, analyze and present these myriad halakhic developments in a cohesive and usable form,” he added.