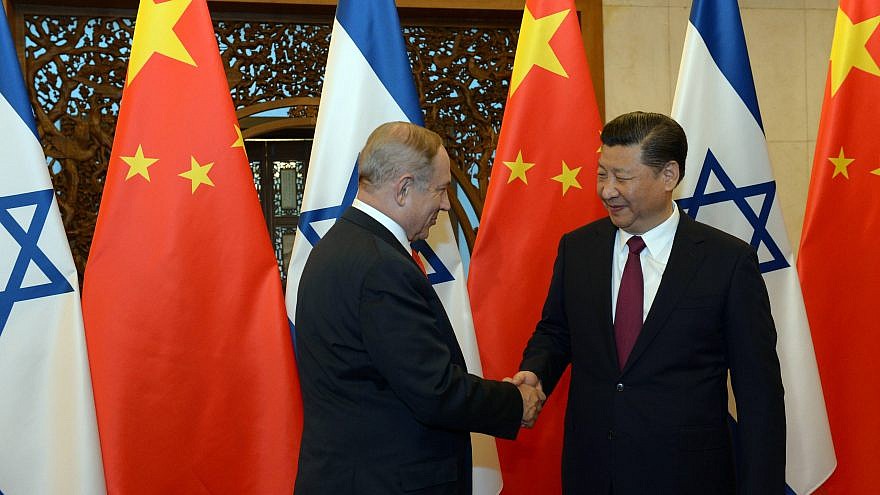

Is there more to the Israel-Chinese relationship than technology?

Roi Feder thinks so. He serves as Israel’s managing director of APCO Worldwide, a global consultancy group, and has helped numerous Israeli industries navigate their way through China’s markets. He contends that Israel has much to offer China, and that it’s a mistake to view the Israel-China relationship through a narrow lens of technology only. Feder has identified at least five areas of potential cooperation, including energy, manufacturing, trade, transportation and finance.

In Feder’s view, what Israel needs is its own Belt & Road Initiative—referring to the Chinese Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) adopted in 2013, and perhaps best thought of as giant economic corridors that on a map follow paths remarkably like the Silk Road, an ancient network of trade routes connecting East and West. “The programs of development … will be a real chorus comprising all countries along the routes, not a solo for China itself,” Chinese President Xi Jinping said on March 28, 2015.

Feder wants Israel to be part of that chorus, and by Israeli BRI, he means finding ways where Israel can plug into China’s global initiative.

Key role as a transshipment hub

Energy is the first area of mutual benefit. Thanks to the discovery of massive offshore natural-gas fields, Israel has become an energy exporter. In February, Israel signed a $15 billion deal to export natural gas to Egypt. In 2019, Israel will make a final investment decision on a 2,000-kilometer pipeline linking its gas reserves to Europe via Greece and Italy. Also in the works is the EuroAsia Interconnector, a project to link Israel’s electric grid to Europe.

“The notion that Israel will actually be able to export electricity to Europe is mind-boggling,” says Feder. He notes that there are plans to lay a data superhighway along the same route.

Energy feeds into Feder’s second area of potential interest to China: Israel as a manufacturing hub.

“There’s a need to have cheaper manufacturing capabilities closer to markets,” says Feder. He recalls a conversation he had with a Japanese foreign-affairs’ official, who thought it was a no-brainer when Feder suggested that companies like “Mitsubishi, Hitachi and Motorola set up hubs in this part of the world, which are closer to European markets.”

Israeli energy conglomerate Delek already appears to be thinking along these lines. The main owner of Israel’s offshore gas fields, it announced this year a feasibility study to set up an aluminum factory in the Negev, “not because there’s any specific need for aluminum, but because it’s a way to use energy beyond just exporting it,” says Feder.

Third, Israel could play a key role as a transshipment hub. Israel is building two new ports: one in Haifa Bay, the second in southern Ashdod. The two private ports will bring the total number of Israeli ports on the Mediterranean to four and break the state-owned monopolies that control the current ports. A Chinese company won the tender to construct the new port in Ashdod. And given that a second Chinese company will take over operations at the Haifa port once it’s completed, it seems that China recognizes Israel’s potential in this area.

Israel, which historically has been separated from the Arab world, could become a land bridge, acting as a corridor for trade between the Gulf States and Europe, according to Feder. Most of the infrastructure is in place with a railroad extending from Haifa to Beit Shean in the Jordan Valley. “Israel is now building a bridge to connect the Israeli side to the Jordanian side,” says Feder. If Israel becomes both a maritime center and transshipment hub, it could certainly be of interest to China, he notes.

The fifth area that Feder has identified is finance. “Israel is a rich country, and it’s going to get richer. And one of the reasons for that is because the amount of money we save is dramatic,” he says. “There’s about 1.5 trillion shekels sitting in Israeli financial institutions.”

Feder notes that Chinese companies want to buy Israeli financial institutions. Israel’s savings could help China invest in technology, infrastructure and other projects.

‘The conversation needs to start happening’

Feder’s main worry is that the Israeli government is still stuck in the mindset of “technology-only.” He says the Israeli government needs to set an overarching policy vis à vis China: “The conversation is not happening yet, but needs to start happening.”

Carice Witte, founder and executive director of SIGNAL, agrees. She says what is required is long-term strategic thinking.

“There has never been a country like China,” she notes. It’s like “a top-down, organized corporation with a CEO that has hundreds of millions of experts in a variety of areas that they can call upon. … Israel will get completely clobbered if it doesn’t get smart with China.”

Feder and Witte worry that there isn’t sufficient knowledge in Israeli foreign-policy circles about China. But they’re hopeful that starting the conversation will lead to necessary changes.