If Rostov-on-Don Chabad-Lubavitch emissary Rabbi Chaim Danzinger has his way, thousands of Jewish soccer fans who will descend on his storied town and 10 other historic cities for the upcoming World Cup games in Russia will leave inspired not only by the sporting extravaganza, but by a taste of the ever-burgeoning Jewish communal life in the post-Soviet era.

The International Sports Travel Agencies Association estimates that 10,000 Israelis are expected at the international soccer tournament, held every four years. Thousands more Jewish fans are expected to fly in from Europe and as far away as South America for the world-renowned soccer games—also known globally as football—between June 14 and July 15 for what is the most widely viewed and followed sporting event in the world, exceeding even the Olympic Games.

Some of the novelty this year derives from the fact that since its inception in 1930, the tournament was never held in the Soviet Union or in any of the 15 former member republics since its collapse. Among the visitors will be many Westerners and Israelis who have never been on Russian soil, even though Israel’s soccer team did not qualify this year for the challenges. Tickets begin at $105 for a group-stage match and top out at $1,100 for the final.

In Moscow, where the games will span two weeks, two halls are being set up to hold an expected 1,000 Shabbat guests for each meal, with the flexibility to accommodate more if needed, said Rabbi Mordechai Weisberg, director of the Moscow Jewish Community Center in the Marina Roscha neighborhood, under the auspices of Russia’s chief rabbi, Rabbi Berel Lazar, a major spearhead of Russia’s Jewish revival since his arrival in 1990.

“We are doing everything we can to ensure that Jewish travelers have everything they need while they’re here,” Weisberg said about programs and accommodations being planned in all of the host cities. “They are already getting many inquiries and orders for meals from all over the world,” Weisberg told Chabad.org. Regarding Moscow, he added: “It’s clear that in a few weeks from now, this will be a different city than today.”

New app to guide Jewish guests around the country

He said the community center has released a phone application that can be downloaded for IOs devices and for Android devices with Jewish traveler information for every host city that includes contact information for each host city local rabbi and synagogue. The Jewish Community Center is also mounting an information desk with multilingual agents providing general and specific information from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. every day during the month-long tournament. The JCC information bank will also be equipped with a hotline to the Israeli Embassy in case of an emergency anywhere during the games, he said.

In Rostov, where 15,000 Jews live among a general population of more than a million people, a spirited Danzinger notes that “it’s the first time my city is going to be a major tourist destination of any kind.” He says that the most important point is that “it will be amazing to see so many people come as proud Jews to Russia to buy kosher food, celebrate Shabbat and sing kosher melodies in a place where for 70 years this was not possible.”

The poignancy of so many Jews attending the games is heightened by the fact that the 1917 Russian Revolution overthrew a centuries-old regime of official anti-Semitism in the Russian Empire, including Jews being restricted to the territory known as the Pale of Settlement, of which Rostov-on-Don was part until 1888. But the previous legacy of anti-Semitism was continued with a vengeance by the Soviet state until its breakup after a seven-decade reign. Under the particularly murderous Soviet regime of Joseph Stalin until his death in 1953, thousands of Jews and others were killed as political prisoners, and Jewish practice took place often under the threat of death or imprisonment.

Rostov-on-Don, which will have matches played by Mexico, Brazil, Switzerland, Croatia, Saudi Arabia, Iceland, Korea and Uruguay, also has the distinction of being the burial place of the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom DovBer Schneersohn, of righteous memory (1860-1920), and the city for whom a most beloved Chabad Chassidic melody—composed by him—is named.

With World Cup travelers already reserved for Shabbat meals, and traditional song and drink planned for the menu, Danzinger said his hope will be that guests will leave with the soulful tune, known as the “Rostover Nigun”, on their lips. He said he planned to introduce the melody as part of his efforts to offer as decidedly a Jewish experience as possible to all between matches.

“It doesn’t have to be an experience exclusively dedicated to the sporting event,” said Danzinger, who has spent the last 10 years with his wife, Kaila, leading the community also known for being the site of the largest massacre of Russian Jews and others during World War II. “It will also be a great opportunity to connect and be inspired by local Jews who despite hardships during Soviet times and occupation are embracing their Jewish pasts.”

In addition to steering the visitors to the most meaningful historical sites, emissaries in the host cities, like Danzinger, plan to offer opportunities for prayer, study and other mitzvahs, and, of course, kosher food, with Friday-night and Saturday Shabbat meals planned for every city.

In addition to Moscow and Rostov-on-Don, World Cup host cities include St. Petersburg, Sochi, Kazan, Nizhny Novgorod, Samara, Yekaterinburg, Kaliningrad and Volgograd. Jewish visitors to the 11th host city, Saransk, which does not have a full-time emissary, will be accommodated by rabbinical students being sent especially for the occasion, said Weisberg. Among them will be many from Brazil to better serve the numerous Jews expected from South America.

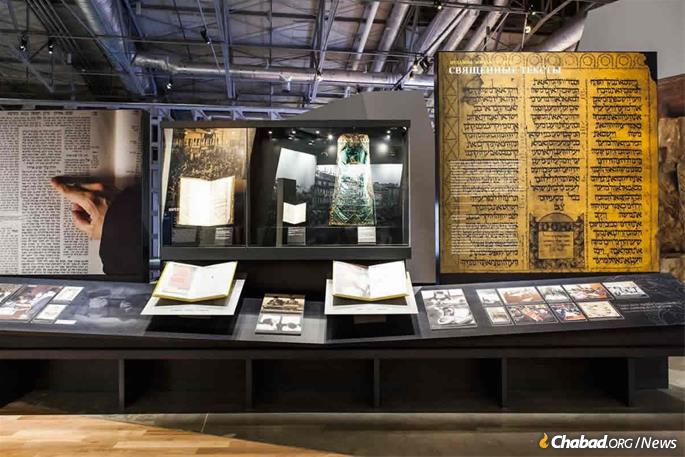

Cities rich in Jewish history

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Pevzner in St. Petersburg is another of the host city emissaries looking forward to welcoming Jewish World Cup tourists with open arms. His is another city rich with Jewish history, particularly Chabad. It is the home of the Petropavlovski Fortress, where Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi—the founder of Chabad Chassidim—was incarcerated with other political prisoners until his historic release on the 19th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev in 1799.

Pevzner will greet tournament guests and host Shabbat meals from his base in the Grand Choral Synagogue, another venerable St. Petersburg Jewish site, and will recommend trips also to the former prison, which now houses a museum.

But the key attraction and message for his visitors says Pevzner, is the same as he told The New York Times after President George W. Bush toured his synagogue back in 2002—an observation, he says, that holds even more true today. “Can you really be a Jew in Russia and not be afraid to practice your religion? I think the answer is yes, you can. If the president comes to this synagogue, then that is a statement that things have changed.”