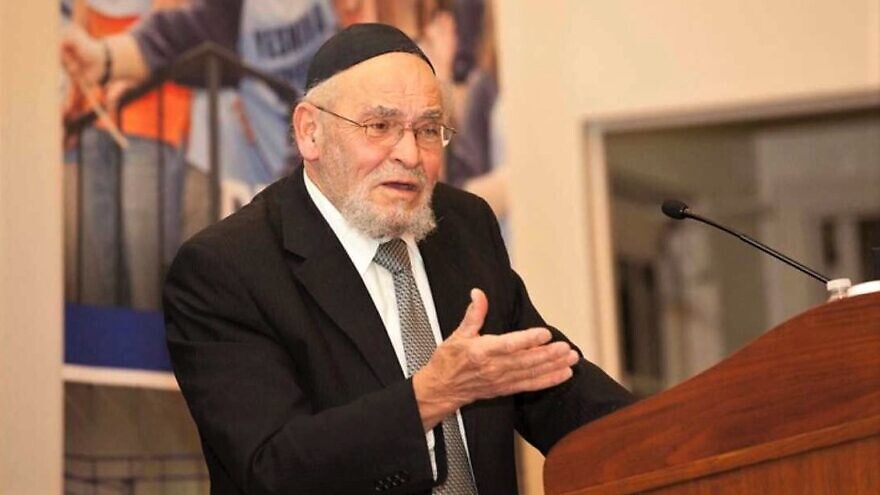

Listening to Rabbi Dr. Moshe Tendler, who died last week at the age of 95, one never knew what to expect. Laced in scientific language, with biblical quotes and references from the Talmud, the professor of biology and Jewish medical ethics at Yeshiva University in New York City, always had an acute comment, controversial statement or stigmatizing view to share.

Tendler was considered in the world of medicine one of the great Jewish ethicists, lecturing and writing regularly on the topic of halachah, or Jewish law, and medicine. He covered such subjects as the Human Genome Project, neonatal salvage, the use of mood-modifying drugs, stem-cell research, organ donation and experimental treatments on human beings.

Perhaps top on his controversy was his belief that norms in the Orthodox world were not being formed based on Jewish law, but rather were “completely dominated by societal factors. … People are trying to recreate something that never was. But that is not the proper way. Halachah has to be dominant. If it is not, everything will go.”

He was born to Rabbi Isaac and Bella Tendler on Aug. 7, 1926, in New York City’s Lower East Side, which he called a “ghettoized European town,” where most “just gave up on observance. It was a complete defeat.” He said that the reason for that defeat was because most were not willing to spend money on Jewish education and instead sent their children to public school.

The elder Tendler was a rabbi at the Kominitzer Synagogue for more than five decades, and headed and taught at the Rabbi Jacob Joseph School, where the younger Tendler studied in grade school. Moshe Tendler later went to Yeshiva University’s Marsha Stern Talmudical Academy for high school, and later Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS), where he received rabbinical ordination in 1949.

During that time, he earned his bachelor’s degree and master’s degree in biology at New York University. While he was innovative in medicine and the medical world, in a 1963 article, Time magazine described him as someone who “spends only part of his time in the laboratory, the rest in his study as a Talmudic scholar.” They wrote that the crude antibiotic medication that he discovered, he gave it the name Refuin, Hebrew for “cure.”

“Hardly had the drug been tried on patients at Montefiore Hospital when calls began to come in from all over the country,” Time wrote, “doctors were being urged by their patients to request supplies—which are not available.”

He later married Shifra Tendler, the daughter of the famed decisor in Jewish law, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein. The two men went on to form a unique bond, where Tendler discussed at length issues of science and medicine, which in the 20th century, due to the many innovations, became a central topic of the rabbinical world. According to Akerman, who for many years was the chairman of the Conference on Judaism and Medicine, he even took Feinstein to Kings County Hospital Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., to learn more about a particular topic in the death of patients there.

Singular to Judaism, Tendler explained at the 1997 International Conference on Jewish Medical Ethics in San Francisco was that most religions leave God outside, inviting them in on Sunday morning. “We invite God in when we eat breakfast, we eat dinner, when we go to sleep, when we buy our clothes.” This forces the rabbinic community to find in ancient Jewish teachings and texts solutions to modern dilemmas.

“Of course, he was a scientist,” says Rabbi Aryeh Ralbag, who heads the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada, of which Tendler was a longtime member. “But his focus was Torah. He had the secular knowledge, but he always wanted to solve the issue according to Jewish law with that knowledge.”

At one conference, in response to someone saying that biology reshaped religion, he said that, in fact, religion reshaped biology. “It had a transgenic impact, it transduced or transformed animal man, into man created in God’s image. A major, major genetic change.”

‘He was strong in his opinion’

Over the years, Tendler had many detractors, including some of the leading experts of Jewish law and medicine, who responded in kind to his attacks. “He was strong in his opinion,” says Ralbag, “and he did not want to be persuaded by political reason. He had an opinion that was according to Jewish law; you could not sway him.”

However, he says, it was never personal—“it was not a vendetta against people.”

In addition to his positions at Yeshiva University and serving as rabbi for more than five decades of the Community Synagogue in Monsey, N.Y., Tendler was past president of the Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientists. He also chaired the bioethical commission of the Rabbinical Council of America and the Medical Ethics Task Force of UJA-Federation of Greater New York. On top of that, he fielded dozens of calls to his home and office about complicated issues of Jewish law and medicine.

One such person was Rabbi Moshe Weiss, who called just before Shabbat with a personal question. He says they had never spoken or met before; despite that, Tendler responded to him with patience and warmth, and, as if he had all day, calmly walked him through the solution.

Years later, as a rabbi in Sherman Oaks, Calif., where he is the director of the local Chabad House, he recalled that encounter with Tendler and its lasting impact. “I always remember how comfortable he made me feel,” said Weiss, “and I have endeavored to do the same, and to not lose my patience, as miniscule as it may be, with anyone asking a question.”

Predeceased by his wife, who passed away in 2007, Tendler is survived by their eight children; and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.