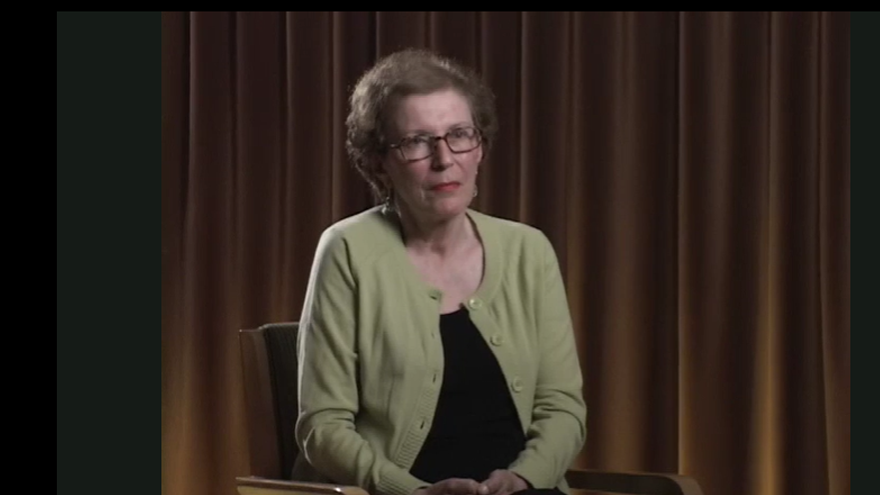

Joan Micklin Silver (1935-2020) passed away on New Year’s Eve. She belonged to a cohort of pioneering American female directors in the 1970s, many of whom were Jewish. Whereas most of her Jewish counterparts deal with Jewish themes in their films, she repeatedly returned to making distinctly Jewish films earning her the reputation of being the “the mother of Jewish feminist film.”

Born and raised in Omaha, she married Raphael Silver and moved to Cleveland where she wrote plays for local theatre groups. In 1967 they moved to New York where she scripted and directed educational films, including The Immigrant Experience: The Long Long Journey (1972) about Poles coming to the United States at the turn of the 19th century. Universal pictures optioned her screenplay Limbo (1972) about the plight of wives of American soldiers missing in action, but dropped her from the production for not softening the assertiveness of its lead character.

To pay homage to the immigrant heritage of her parents, she shopped the idea of adapting Abraham Cahan’s Yekl: A Tale of the New York Ghetto to the screen, but encountered skepticism about the competence of women directors and the box-office potential for such a decidedly Jewish film, much of whose dialogue was in Yiddish. Her husband responded by forming the production company Midwest Films and raising $350,000 to fund Hester Street (1975). Well received on the European film festival circuit, particularly at Cannes, it opened in the United States at a rented theatre in New York and received glowing reviews helping it secure broader distribution. Hester Street eventually grossed $ 5,000,000 in ticket revenues and won Micklin Silver a nomination for best comedy screenplay from the Writers Guild of America and Carol Kane an Oscar nomination for Best Actress. Released at the height of the ethnic roots and feminist movements, it was, as Hasia Diner has remarked, “the right film at the right time.”

Cahan’s story focused primarily on the unbridled Americanization of Yekl and how it drives him to divorce his embarrassingly “greenhorn” wife Gitl in favor of Mamie, an assimilated Jewish immigrant woman he had been courting before Gitl joined him in New York. Micklin Silver deliberately shifted the emphasis to what she described in an interview as Gitl’s “amazing journey in terms of where she started, how she came over, and what happened to her from there.” From the moment Gitl and their son Yosele arrive at Ellis Island, Jake forces them to Americanize by cutting Yossele’s peyes, renaming him Joey, and teaching him how to play baseball. He berates Gitl for wearing plain long dresses and a sheitel or babushka to cover her hair and for speaking Yiddish. Jake’s landlady Mrs. Kavarsky mentors Gitl on how to look like an “American lady” by discarding her sheitel and modest clothes for more fashionable garments and hairdo. When Jake glimpses Gitl’s new appearance, he assumes she has purchased a more stylish wig and tries to rip it off her head. In the course of their ensuing argument, Gitl blurts out that she knows about Mamie whom she calls a “Polish whore.” Mrs. Kavarsky attempts to reconcile the couple, but Jake walks out. Kavarsky assures Gitl, “Don’t worry, this one will come back,” but Gitl can no longer tolerate him and replies, “I don’t want him back. Genug-enough!”

Micklin Silver endows Gitl with more agency than she possesses in Cahan’s story. Deeply wounded by Jake’s infidelity, Cahan’s Gitl possessively holds onto Joey to signal he will remain with her, but never announces her decision to leave Jake. Instead, Jake raises the prospect of divorce and purchasing Gitl’s acquiescence. The movie fabricates a scene of Gitl stonewalling Mamie’s lawyer until he offers Mamie’s entire nest egg to obtain her consent. Although both versions monitor Gitl’s growing fondness for the kindly and pious Bernstein who is teaching Joey Hebrew, only the film reverses the gender roles by having Gitl propose to him. In the closing scene, a confident and stylishly dressed Gitl strolls with Bernstein discussing the store they plan to buy; Cahan’s Gitl still feels grief-stricken over the dissolution of her marriage.

After directing several feature films and television movies, she directed Crossing Delancey (1988) which is considered the “ultimate Jewish rom-com.” When a love story involves Jewish characters in Hollywood films, their paramours are usually Gentiles because the star-crossed plotline engenders comical incongruities or tragic conflicts. Crossing Delancey achieves the same effect by matching Izzy, a secularized modern Jewish woman who works in a trendy bookstore on New York’s Upper West side, with a Jewish man named Sam who has remained on the city’s Lower East Side to run his father’s pickle business. Izzy is enthralled by the famous author Anton after he reads from his novel at the bookstore where she works. Bubbie, Izzie’s grandmother worries that Izzy will not find a nice Jewish man to marry. Consequently, she hires a matchmaker to fix Izzy up who, in turn, arranges for Izzy to meet Sam. Izzy resents this meddling and assumes there can be no chemistry between her and someone like Sam. Sam proves to be more intriguing than she expected. He’s handsome and modern even though he retains a strong Jewish identity. Drawn by the allure of Anton’s celebrity, Izzy quickly learns that he is really looking for a mistress and secretary. Despite repeated efforts to discourage Sam’s interest in her, it finally dawns on Izzy that he possesses endearing qualities that merit her romantic attention.

Micklin Silver exudes an affectionate Jewish sensibility in Crossing Delancey. Whether evoking the ambiance of the Lower East Side, having Sam mention that he said “a special bracha” before he gave Izzy a new hat, depicting Izzy’s attendance at the bris of a baby boy born to one of her girlfriends, or peppering the dialogue of Bubbie and the matchmaker with Yiddish words and phrases, she instills the movie with almost as much Jewish content as appeared in Hester Street. In a way Crossing Delancey could be interpreted as a sequel to Hester Street with Bubbie as an elderly Gitl striving to maintain Jewish continuity by preventing the intermarriage of her granddaughter. Izzy’s escape from the old Jewish neighborhood resembles Jake’s distancing himself from his immigrant roots. Sam’s attachment to Judaism parallels that of Mr. Bernstein, the boarder in Hester Street whose kindness and piety gradually render him in Gitl’s eyes a desirable spouse to replace Jake.

Micklin Silver has demonstrated a commitment to portray her Jewish heritage in film and other media throughout her career. She directed the 13-part anthology Great Jewish Stories from Eastern Europe and Beyond (1995) for National Public Radio, Showtime’s remake of Rod Serling’s In the Presence of Mine Enemies (1997) about a rabbi in the Warsaw Ghetto, and her last independent feature film A Fish in the Bathtub (1998) about a bickering Jewish couple. In 1995 the National Foundation for Jewish Culture bestowed its Jewish Cultural Achievement Award in the Media Arts on her. Documentarian Marlene Booth rightfully credits Micklin Silver with “showing not only that women can direct films but that films about Jewish topics can succeed with Jews and non-Jews alike.”

Lawrence (Laurie) Baron, now retired, served as the Nasatir Professor of Modern Jewish History at San Diego State University. He served from 1988 to 2006 as director of SDSU’s Lipinsky Institute for Judaic Studies. He was the founder in 1995 of the Western Jewish Studies Association.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World