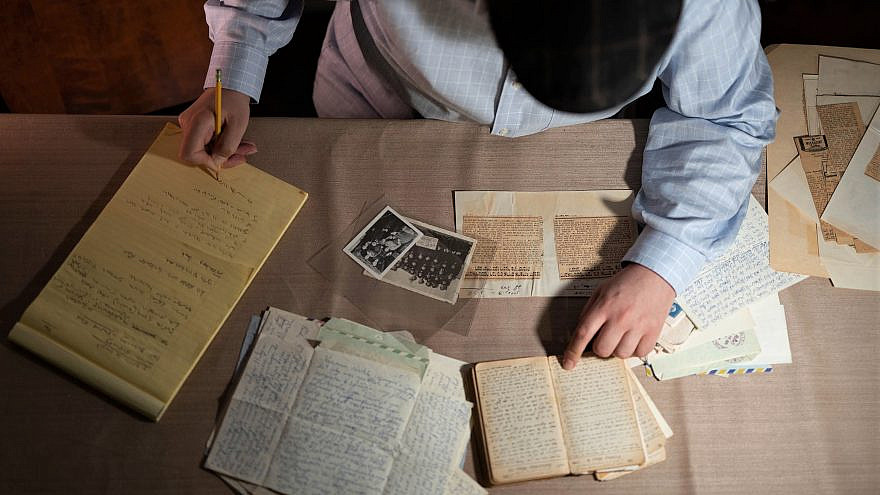

After many years of trying to locate the postcards written by the parents of Rabbi Chaim Meir Bukiet during the war, they were finally in my hands. As I flipped through them, several names appeared over and over again. I can only imagine why Avraham and Ruchla Bukiet had to reiterate them. While I could not understand most of the writing, those names—Brzyski, Rodal, Goldstein—stood out like a sore thumb.

Mottel Brzyski and Chaim Meir were both from Chmielnik, a small town of 12,000. Though four years younger, Mottel had joined the Lubavitch yeshivah in Otwock, Poland, where Chaim Meir took him under his wing. Their parents’ similar fate brought them closer, and they considered each other brothers for life. Even after arriving in New York and raising families, they studied together daily.

Rabbi Bukiet was a Talmudic scholar and dean of the central Chabad yeshivah in New York. He would easily discuss any passage of Jewish scholarship but refused to discuss his own Holocaust experiences. Lacking maturity and insight into his pain, from a young age, I still pressed him to do so. He only spoke to me about his life story a few times until his daughter Ruchie Stillman convinced him to sit down for an interview with the USC Shoah Foundation founded by Steven Spielberg.

Minutes later, as the interviewer continued to press him about his delay in leaving German-occupied Poland, he said: “If I would have had permission from my mother, I would go [right away]; there’s no question about that.”

In the end, despite his mother’s objections, he did go. The deep gash it left behind, specifically for his mother who had mostly raised him alone, was deep.

‘You took him away from us’

Mottel Bryzski, who was already safe in Lithuania, was one of the students who encouraged Chaim Meir to leave. So did his mentor in Chmielnik, Rabbi Yosef Goldstein, and his friend from yeshivah, Yosef Rodal. In the eyes of Ruchla, they were conspirators in severing her connection with her son.

In November 2019, as I told the story of my grandfather’s life at the iconic Central Brooklyn Public Library, dozens of unfamiliar faces crowded the small lecture hall. At the end of the lecture, many of them approached me at the dais. They told me that they were children and grandchildren of fellow “Shanghai” survivors. They added their details, anecdotes and appreciation.

But a conversation with Chaim Kohn, Mottel’s grandson, surprised me most. I had asked his grandfather, Mottel Bryzski, to tell me his story many times. I will never forget the scene when I first made the inquiry; Mottel’s wife stood on one side of the table, while he sat on the sofa unable to make eye contact. He could not get the words out. Immediately, I understood that it was just too painful for him.

Back in the library, Chaim Kohn told me that shortly before Mottel’s passing, his children compelled him to tell his story. By the end of the day, Chaim had sent me seven-plus hours of interviews.

In the recordings, Mottel spoke of his childhood friend, Chaim Meir, and their experiences together. Three hours into the interview, he tells of the numerous postcards he sent to Chaim Meir in Chmielnik, encouraging him to leave. “I wrote that Grandfather is here, and he wants you to come,” he said in Yiddish, referring to the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, who had encouraged and funded the students’ escape from Poland.

It would take a few more urgent postcards until Chaim Meir would finally leave home. Mottel did not even know Chaim Meir had fled until a scathing card arrived from Avraham and Ruchla Bukiet. The postcard had said that they had not heard from Chaim Meir for months and feared the worse, recalled Mottel. They wrote: “What have you done to our son? You took him away from us.”

‘A huge emotional charge’

Speaking of those moments, he summarized that they had a gevaldige taane, a scathing reproach on his involvement in their son leaving Poland. He said that this was just one of several cards he had received from the couple. Eight decades after they were written, when I finally had 13 postcards from Mottel’s family, I needed help interpreting them.

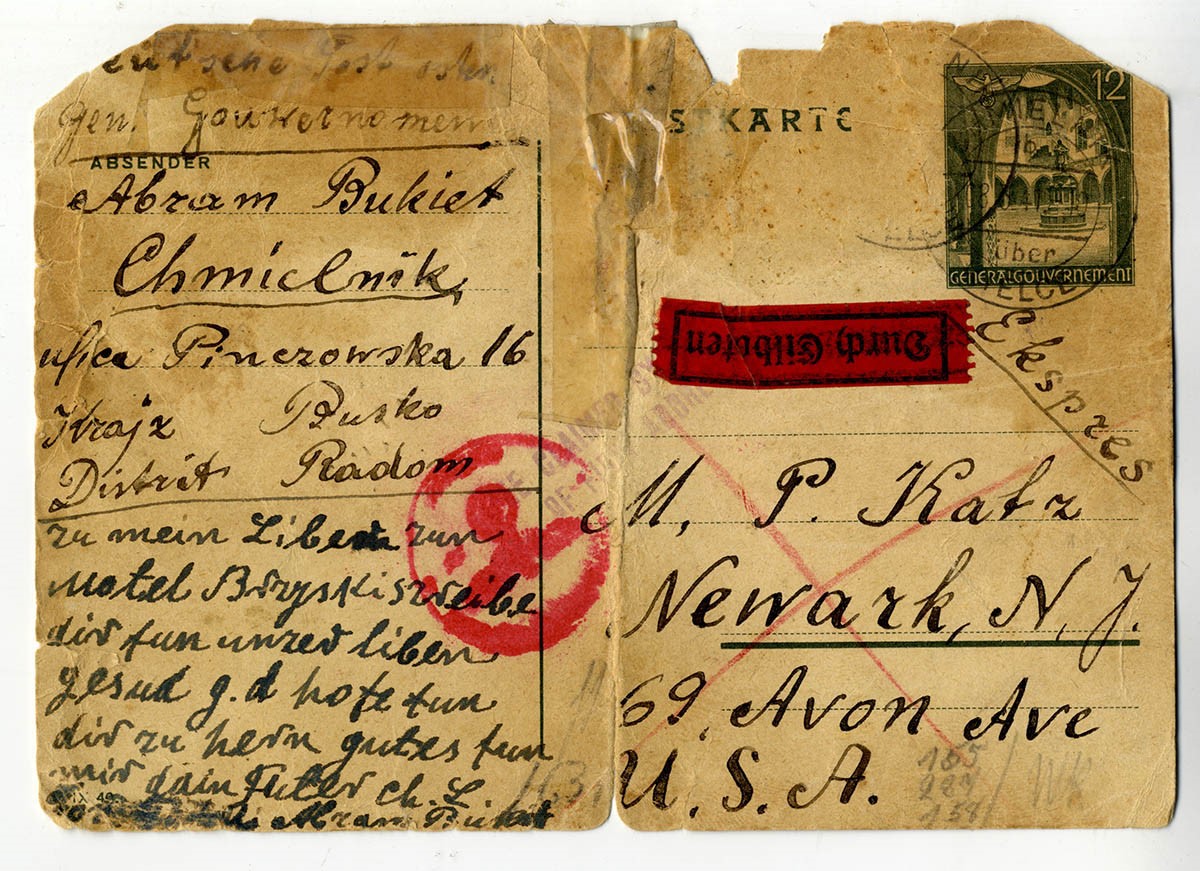

They were all stamped in red with Nazi insignia, and the inscription Oberkommando der Wehrmacht–Dienststempel—the high command of the Wehrmacht Armed Forces of Germany postal stamp. I understood this indicated that the letters were written under duress and veiled in code, as Rabbi Bukiet said in his Spielberg interview.

The first cards that I had translated were written in German script but Yiddish wording. They were from Mottel’s father. They were heart-wrenching and spoke of their difficult circumstances—the starvation, lack of livelihood and his mother’s death. It spoke of his longing for his son. “The One in Heaven should help that we will see each other soon with joy,” one April 1941 postcard read. Another from June ended, “The One in Heaven should help us out of here, and we should all meet together soon.”

It was more difficult finding someone to translate the postcards that were written in Polish. I turned to Tomasz Brzostek, a historian from Otwock, the city where Chaim Meir and Mottel studied. He said that the language was old Polish and difficult to decipher, but he was glad to have made the effort. Tomasz wrote to me that “these words have a huge emotional charge. There is love and concern for the closest family in them. You can feel insecurity and fear in them.”

While he was right that they were haunting, he did not understand the code words. The postcard, written just before Passover, began with the worries and hopes of any parent: “My dear, kind son Chaim Meir. I am writing that we are [OK]. Thank G-d, the news from you is always good. We are waiting with no patience for any letter from you. Also write to my father in Wiślica. Give him news about your health. … Regards to all of you and with wishes for a joyous holiday.”

They then made an intentional reference to the friends who had encouraged him to leave. “Greetings to your friends, M. Brzyski and Rodal. Please reply quickly. Your dear parents, Abram and Ruchla Bukiet.”

Chaim Meir was heartbroken when he received their letter. He connected the mention of his friends to their pain and disappointment that he’d left them behind. For weeks, he could not respond. Two months later, the Bukiets wrote to Mottel imploring about their son’s well-being: “My beloved son Chaim Meir is with you. I [have not] received a letter from him, so I am writing. … We wish to rejoice with you. Greetings to my beloved son.”

However, they were unaware that the students, who were supposed to continue to New York, had been banned on the premise that they may be spies. In the meantime, they continued sending postcards to New York. When Chaim Meir, in 1946, arrived in New York, the cards were waiting for him.

In one of those postcards dated March 1941, his parents wrote: “Warm regards to him [Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn] and the whole family [the Lubavitch community]. Warm regards to all our dear brothers [your fellow students].” Again, they sent regards to those who had encouraged Chaim Meir to leave—Rodal and Brzyski.

My grandfather, Rabbi Bukiet, wanted to blot out his war experience. Everything that came as a result of his survival—his marriage to the love of his life, his work as an educator, his Talmudic studies, and his beloved children and grandchildren—was at the expense of his parents’ pain. For decades, he lived with this embroiled reality.

As the story of Rabbi Bukiet continues to unfold on my computer screen, the holiday of Passover nears. Every document and interview I discover reminds me of how the Israelites in Egypt did not want to leave their comfort zone, despite the difficulties. Even after escaping Egypt, many wanted to turn back.

It was a difficult journey that culminated in the creation of the Jewish nation and entering the Land of Israel. Today, we have a bountiful appreciation for the gift the Jewish nation has brought to the world.

Chaim Meir’s exodus from hell was immensely difficult, too. It came with great pain, but there is also comfort and meaning in the thousands of students he taught, and the large family he created who have become Jewish leaders across the globe.