The world will mark Yom Hashoah—Holocaust Memorial Day—on April 7-8 with particular attention on the 80th anniversary of a campaign against the Jews of Eastern Europe that was nothing short of mass murder. This deadly Nazi plot would put the close and loving Jewish family to the most painful of tests.

The tensile and enduring strength of the Jewish family is on full view in a new online exhibition from Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem called “The Onset of Mass Murder: The Fate of Jewish Families in 1941.”

Timed to release the week of Yom Hashoah, the exhibition reveals a dozen never-before-published stories of Jewish families caught in the web of the Nazis’ “Operation Barbarossa,” an organized rout of the Jewish communities in Soviet-controlled countries beginning that summer. Carried out by Einsatzgruppen SS mobile killing units teamed up with local authorities and citizens, “Barbarossa” cut a bloody swath across the Soviet-controlled lands of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Eastern Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Romania and Yugoslavia.

Four years later, only the third of Europe’s Jewish population who survived were left to tell their story of a love stronger than hate, stronger even than death itself.

One has only to look at pictures of German soldiers looking on while the locals did the killing to grasp the idea, points out Katz. “The Germans gave the locals the freedom to express their own anti-Semitism in the most deadly way.”

By the end of 1943, more than 1.5 million Jews from the region—representing one-fifth of the 6 million Jews who perished during the years of the Holocaust—had been murdered.

The grisly routine, repeated over and over around the region, consisted of rounding up a community’s Jews, taking them to a spot on the outskirts of town or the local Jewish cemetery, and forcing them to strip and surrender their valuables before gunning them down. They were then shoved into one of thousands of mass graves, many of which historians say have yet to be discovered. The most famous of these killing sprees was Babi Yar near Kiev on erev Yom Kippur of 1941, where 33,771 Jewish men, women and children were massacred.

“We want to show their faces, give their names, remember them as human beings, as part of our Jewish family,” says exhibition curator Yona Kobo. “To go back and trace the beginning of mass murder as Nazi policy, to see all the professors, teachers, doctors they killed—and so many babies—many of them murdered by their neighbors.

“Of all the exhibitions I’ve worked on, this had been the hardest,” she adds. “I kept seeing my own grandchildren who are so cute and thinking if they lived in those days people would look at them and think they were scum and had no right to live.”

Giving them names

In 1933, young Ida Bernstein’s family encouraged her to leave their home in Ylakiai, Lithuania, for the hard-scrabble existence of pre-state Palestine. “My mother went with their full support,” says her son Yitzchak Lev. “She was so attached to her family, and she knew how much they worried about her being so far away.”

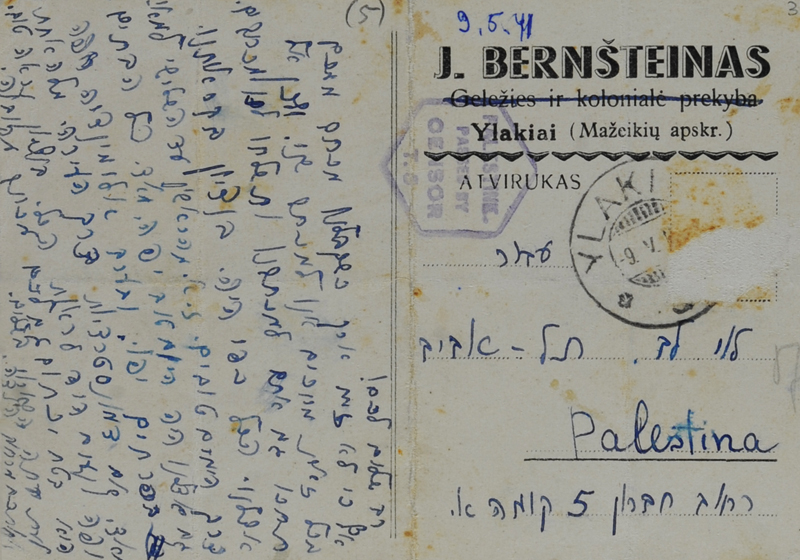

Indeed, a postcard written on May 9, 1941—one side in the Yiddish of her parents, Eta and Jacob, and the other in Hebrew by her sister, Hinda—echoes these feelings. “Dear Ida, we are very worried about you,” her father wrote. “For God’s sake, write often, we are waiting for good news from you. Mother doesn’t sleep and mentions you all the time.”

“My mother knew how much her family looked forward to joining her here in Israel as soon as the war was over,” says Lev. But two months after sending the postcard, that dream died as her parents and four of their seven children were killed with Ylakiai’s other 300 Jews. By August 1941, not a single Jew was left in town. Since two more of her siblings were murdered elsewhere during the war, his mother was the only one of the family to survive.

The Bernsteins are among the dozen families featured in the exhibition—families whose stories and photos bring this terrible time and place to life. Those left to tell the tale typically fell into one of three groups, Kobo points out: Jews exiled to such far-flung Soviet outposts as Siberia or Kazakhstan, those who hid with groups of partisans in the forests and others—many of them children—taken in by non-Jews.

In such situations, untold thousands did the hardest thing any parent could ever do: Giving over their beloved child to strangers, entrusting them to people who, though they may feed and care for them, would not raise them in the time-honored ways of their forebearers.

Halina Tenenbaum of Lvov, Poland (now Ukraine) was an only child who was born into wealth; her father, Jonasz, was a lawyer and professional violinist. She was 13 in the summer of 1942 when her father dropped her off at the home of a Christian friend. Within the year, he’d been part of a roundup of Lvov Jews and taken to the notorious Janowska concentration camp, where he was killed. Her mother, Stephania, survived hiding with other Jews in a movie theater until one month before liberation, when someone turned them. They were among the last Jews of Lvov to be killed. But their sacrifice paid off: Their child survived. At war’s end, Halina immigrated to an Israeli kibbutz, where she lived out her years as Ilana.

And, in the case of the Knesbach family of Vienna, there is a poignant moment in 1939 where Fanny, whose parents Osias and Jetti, in an effort to get her out of harm’s way sent her to England after she’d finished her medical studies. Seeing them receding into the distance as the train took her away from home—and towards safety—she wrote, “I stuck my head out … I wanted to keep the imprint of my parents’ faces. For a few yards, they kept up with my window while the train was still moving at a walking pace.

“ ‘Don’t cry, Fannerle, we rejoice that you are leaving!’ and tears were streaming down Mama’s cheeks. ‘B’shanah haba’ah b’Yerushalayim!’ Papa shouted above the hissing steam. ‘Next year in Jerusalem!’ The train was gaining on them. … I held my handkerchief out of the window at arm’s length and caught a last glimpse of them. Two tiny figures. Then tears blinded me completely. … I may never see them again! ‘Never, Never’ went the mocking rhythm of the train.”

Sadly, Fanny’s fears proved to be well-founded. Her parents, trying to escape to Israel with other Jews, were murdered by the Germans when their ship was stranded in Yugoslavia.

The Jewish woman takes charge

With so many men taken to work in forced labor camps, much of the family life-and-death decision-making fell squarely on the women.

“It was a time when the job of the women became enlarged, they had to be the ones to keep their families alive and ensure that Judaism would continue,” says Rebbetzin Esther Farbstein, an Israeli historian who founded and directs the Center for Holocaust Studies at Michlalah–Jerusalem College and is author of Hidden in Thunder: Perspectives on Faith, Halachah and Leadership during the Holocaust.

“Where did their hope and strength come from in such a horrible place? How did they do it?” she asks. By keeping their traditions as best they could, she says—by lighting threads on Friday nights and saying the candle-lighting blessing over them, by fasting on Tisha B’Av even when they knew they didn’t have to. “And by keeping pictures of their past in their minds and envisioning meeting their loved ones again and going home together when all this was over.”

It was a trial by fire that forged strong women, enriching those who survived with knowledge well beyond the generations of Jewish women before them, empowering them to teach and transmit Jewish tradition to their children and communities.

This doesn’t surprise historian Katz. “All the jokes made about Jewish mothers don’t recognize the truth,” he says. “The Jewish mother has made the survival of the Jewish people possible. In fact, more than anything, since the destruction of the Second Temple—when we had no temple and no state anymore—the rabbis knew the Jewish home would be the key to our survival.”

Tragically, there were times when family love and loyalty actually cost lives. The exhibition features the invitation and group photo for the wedding of Zalman Jershov and Luba Pilschik on Dec. 26, 1937. Four years later, all the Jews of their hometown of Zilupe, Latvia, including many in the photo, were ordered into the market square. From there, they were taken out of town and shot by members of the local home-guard militia.

On the way to the killing fields, Zalman, with his wife and two small sons, was recognized by a local policeman with whom he’d served in the Latvian army who offered to pull him out of line and save his life. A member of the militia reported that Zalman refused, saying he would remain with his family and the others, including his brother Yisrael and his family. Within minutes of that fateful decision, they were all dead.

“ ‘Stay together,’ my mother said. We wanted to stay together, like everyone else,” Nobel Prize-winning author and human-rights advocate Elie Wiesel wrote in All Rivers Run to the Sea. “Family unity is one of our important traditions … and this was the essential thing—families would remain together. And we believed it. So it was that the strength of our family tie, which had contributed to the survival of our people for centuries, became a tool in the exterminator’s hands.”

But 80 years later, the Jewish family lives on.

“When I think of the power of family,” says curator Kobo, “I can’t help but remember my mother, who survived the Holocaust and told me before she died that the proudest moment of her life had been when I joined the Israel Defense Forces. ‘Now we’re not powerless anymore,’ she said. ‘And my daughter is one of the soldiers protecting us.’ ”