Sometimes, boredom becomes the mother of inspiration.

Holocaust educator Adi Rabinowitz Bedein was listening to presentations from top scholars in her field at a conference she attended last year. One read the entire paper. Another showed a video, with no sound, of scrolling photos for half an hour.

“I was expecting to be inspired to learn, and let’s just say I fell asleep in the middle of it,” Rabinowitz Bedein, 37, told JNS.

The private Holocaust lecturer and educator, Yad Vashem tour guide and director of ambassadors at Kanfey Dror, an NGO that combats social bullying in children’s spaces, went home feeling frustrated. (She didn’t want to identify the conference or its location, and told JNS that she respects the scholars in question and their work.)

A heavy LinkedIn user, Rabinowitz Bedein saw a message on the career networking site from Ohad Tadmor, 32, a Tel Aviv-based creative producer and game designer who shared a similar experience attending what he described as an old-fashioned presentation. His participation had also lowered the average age of attendees significantly.

Tadmor explained to Rabinowitz Bedein that he developed the educational video game “Emil: A Hero’s Journey” based on his grandfather’s Holocaust survival story. Rabinowitz Bedein, stimulated by the idea of creating something new and fresh in her field, created the Network for Innovative Holocaust Education last July. The group has already drawn 140 dues-paying members from 23 countries.

Rabinowitz Bedein predicted to JNS that the group and its members “will learn how to be innovative, which means relevant.” For her, that will come from a new generation of Holocaust educators developing tools to teach a new student generation.

“If it’s relevant to your life, then it will be interesting for you,” she said.

‘Can’t just be a story’

To be relevant, Rabinowitz Bedein thinks that Holocaust education must address altruism, compassion and resilience.

“When I’m hearing a testimony—this happened there, and this happened to them and then they got there,” she said. “I’m looking for the insights. It can’t just be a story.”

One reason is that harrowing tales of Holocaust survival simply don’t register with a generation for whom the Shoah is largely ancient history. That’s coupled with the fact that many children either don’t live near (let alone with, as previous generations did) their grandparents or theirs are no longer alive as Jewish adults wait longer to start families, and the multigenerational unit becomes fewer and farther between.

And that is why, Rabinowitz Bedein says, new teaching and educational methods must be put into place to make those critical stories more impactful, especially in an age where students are drawn to more interactive and more visual teaching mechanisms.

To revolutionize Holocaust education, the network must get away from the private club atmosphere that Rabinowitz Bedein says has permeated Shoah education.

She was careful not to disrespect the established field of Holocaust studies while noting that there are organizations, and even networks like hers, that focus expertly on designing courses to prepare Holocaust educators.

“So I’m not going to do a session with insights about the Holocaust in Romania. Other organizations are doing it perfectly well,” she said. “We want to focus on the tools and the methods, but it’s also about the message, the technique.”

Rabinowitz Bedein envisions a sustainable community of educators, authors, artists and scholars in a collective that communicates regularly via a WhatsApp group and holds monthly networking sessions.

“It’s about collaboration and creating something new together—interfaith, interdisciplinary, international,” she said.

The group is also pursuing sponsors to develop grants for research, project development and collaborations.

“The vision is to have a digital virtual museum for the innovative projects that will be created,” she added.

‘It’s an interactive session’

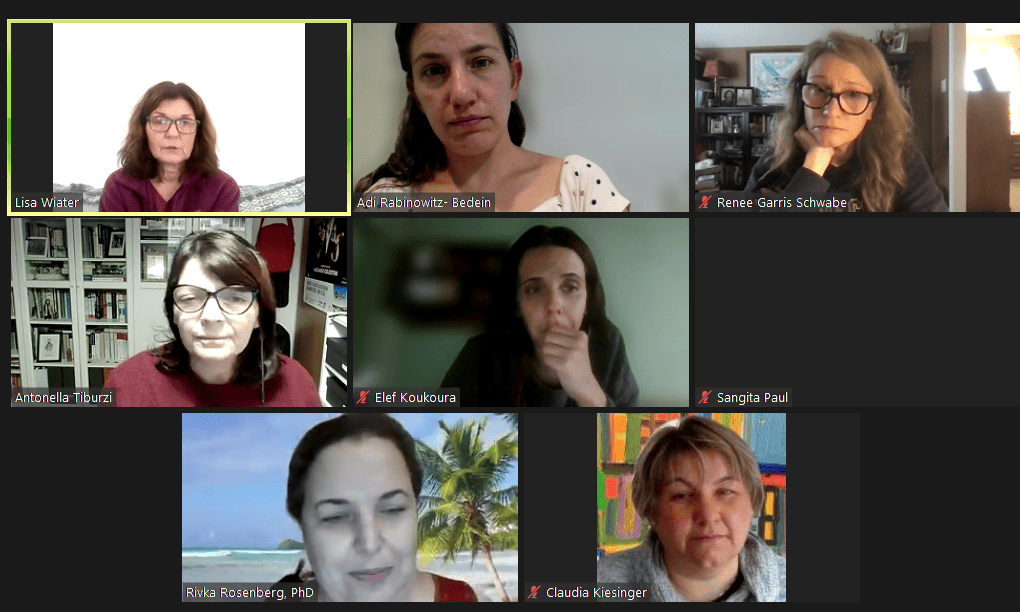

Twice a month, the group holds educational sessions, during which a member of the network shares a project or a tool with the group that he or she is developing.

“It’s not just another lecture. It’s an interactive session,” Rabinowitz Bedein said. “It’s all about how the presenter can help the other members, but also how we can help him. Everyone has a challenge that they want to promote. They need funding, connections.”

Ofer Nidam and Stav Cohen Lasri, both members of the network who come from the startup world, designed a social-media tool that can be used to fight Holocaust denial.

Another member, Luc Bernard, created a video game, “The Light in the Darkness,” based on the story of the Holocaust in France. That game became surprisingly popular in Saudi Arabia and, according to Rabinowitz Bedein, in Malaysia.

Danica Davidson, a journalist who is a member, wrote a children’s book with the late Eva Mozes Kor, a renowned Holocaust survivor.

The network also introduced Davidson and Mehak Burza, a member from India who wrote a thesis on Kor. Davidson and Burza plan to collaborate on a lecture timed to Kor’s birthday on Jan. 31.

Oct. 7

The network was some three months old when Hamas terrorists attacked Israel on Oct. 7. Group members provided one another with comfort and solace, and the network has been trying to reframe Holocaust education to address that Black Shabbat and its aftermath.

One member realized that she just cannot teach about the Holocaust as she used to and now must address Oct. 7 as well, according to Rabinowitz Bedein. “She needs to go all the way back to the roots of antisemitism,” she said. “This community is one thing that can help.”

The network postponed its scheduled program for October and upon the suggestion of a non-Jewish, Greek member, made a “coffee pal” group, in which 70 members from Israel and the rest of the world meet and support one another.